When the finale of Search Party‘s first season “aired” back in November of 2016, viewers were met with a denouement very unlike any they’d ever witnessed or expected. One that proves the oft touted adage, “Be careful what you wish for”–and what Dory (Alia Shawkat), our mixed up, in search of meaning non-heroine, wished for was some form of satisfaction in finding Chantal (Clare McNulty), the former college classmate she barely knew who went missing, yet still felt inclined to search for as a means to feeling a purpose in her void of a millennial life. What she got instead was the dead body of an obsessive P.I. named Keith (Ron Livingston). After Dory’s increasingly ex status’d boyfriend, Drew (John Reynolds), sees her being attacked by Keith in Montreal, where the trail led to Chantal, an over zealous blow to the head prompts his murder.

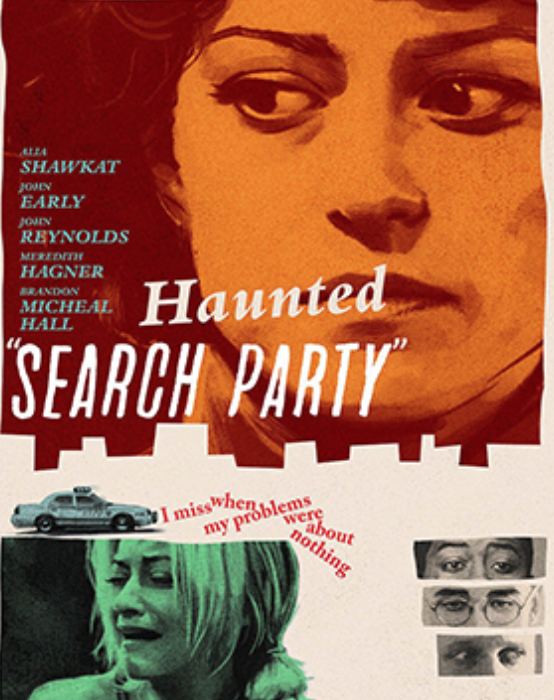

As Dory puts it over brunch with Elliott (John Early) and Portia (Meredith Hagner) after returning from Montreal, “I miss when my problems were about nothing.” It’s, by far, one of the most Generation Y sentences ever to be uttered. And now that she’s managed to make all three of the people closest to her in life complicit in a crime she never intended to commit, Dory’s anxiety, feelings of isolation and need for self-denial are more heightened than ever. In short, she’s having some The Tell-Tale Heart delusions as a result of this repression. It doesn’t help that no one in her group will discuss the “incident” with her, each one instead preferring to suppress the memory in different ways. For Elliott, it means throwing himself into the memoir-ish book he’s supposed to be writing after getting a deal with a publisher for lying about having stage four cancer in season one, while for Portia, it entails going to work on a play about the Manson murders directed by the equally Manson-y in manipulation Elijah Clyde (Jay Duplass). And with Drew distancing himself altogether from everyone involved, he, too, finds a work fixation in the form of puppeteering the implementation of suspicion and jealousy in a co-worker, a strategy he hopes will give him a chance at a transfer to Shanghai, where he prays extradition is impossible. So yeah, basically everyone is in the midst of a breakdown in their bid for ignoring the dead body, which is already drawing questions from people like Keith’s ex-wife, Deb (Judy Reyes), determined to figure out what’s happened to the father of her child. And oh yes, that factor–that he has, or had, a daughter–only further compounds the guilt everyone involved is trying to extinguish with their cavalier statements like, “My publishing team is going to turn my life into a board game!” And this is perhaps what co-creators Michael Showalter, Sarah-Violet Bliss and Charles Rogers execute with even greater skill in season two: exhibiting the utter vanity and self-involvement of the current generation, paired with an evermore latent biological need to feel some sense of remorse for bad behavior.

It is their overt aura of self-indulging narcissism that prompts their eventual blackmailer, April (Phoebe Tyers)–Drew and Dory’s hoarding, deranged busybody of a neighbor–to explain her motive in threatening them as follows: “I don’t like the way you carry yourselves…and I don’t think you should kill people.”

The way the quartet “carries themselves,” as it were, does indeed say quite a bit about the extent of egoism posing as “being lost” in the millennial epoch. Perhaps the most overt case in point of this is both Elliott and Portia’s lack of desire to work at anything other than being lauded, hence their non-conventional professions. As Elliott declares to a room full of people on his editorial team after having an epiphany in rehab, “Here’s the truth. I don’t wanna work. I don’t like working. Working sucks… It’s the discomfort of hard work.” His publisher counters, “Okay, yeah. You know, who likes to work? Not me. You know, no one likes to. But, uh, we have to. It’s just kind of what you gotta do in life is work.” Elliott bowls them over further with the gall of his belief in being unlike the average person by insisting, “No not for me. Not for me at all. I mean I have a lot of stuff I wanna say in my lifetime but I’ve realized I wanna find the easiest way to say it… Working feels bad and I don’t wanna work one more day in my entire life.”

If he were willing to write further about this, it could very well serve as the manifesto for the work ethic of now, and how it’s driven so much by the millennial’s false belief in his or her specialness. Elsewhere, Portia’s often condescending mother, Mariel (Christine Ebersole), makes the dig, “I don’t know how she does it. She takes after her father. He could clip his toenails for ten minutes and call it a full day.” This constant and glaring spotlight on directionlessness in the present stemming from the cognizance of having no interest in what a job or profession entails is one of the most brilliant and accurate facets of the show. And, of course, it’s telling of what happens when one has “too much time” on her hands, the type of trouble she’s liable to get into without the routine of a daily grind far duller than the ramifications killing someone.

In the wake of the murder, Dory finds herself–in typical aimless fashion–gazing out at the city from her perch near a railing. A girl nearby snaps photos of her and explains, “I’m using my day to take pictures of people who look truly happy and I couldn’t help but feel that you are so at peace.” Ignoring the underlying reproach about the kind of clientele living in New York at the moment, the seeming paradox of that statement is, in actuality, quite true, for Dory really is at peace in her state of flux and misery. Flux and misery is simply the status quo–and being in any way healthy, happy or satisfied would really fuck with that quo. Which is precisely why the conclusion of the second season is, once again, expected in its unexpectedness.