On February 15, 1985, thirty years ago today, The Breakfast Club, a modest teen movie that read more like a play than a film, was released in theaters. The effect? Astounding. Up until that moment in time, there had never been anything like it (other than John Hughes’ first directorial effort, Sixteen Candles). Keeping the subject to a bare bones minimum–the struggles and dilemmas of the teenager–Hughes’ masterpiece would go on to gross $51,525,171 on a $1 million dollar budget.

Looking back on it now, the film remains just as profound reverberant as it did then–although, as Molly Ringwald points out in a recent interview, if it had been filmed in 2015, “no one would have talked. We would have all just been sitting there with our phones texting our friends.” This salient remark further solidifies just how important The Breakfast Club was as an illumination of teen issues both then and now (minus the internet). Without its existence, we might never truly understand the breadth of adolescent psychosis.

Hughes’ script, peppered with some of the most quotable lines in cinema history (see: John Bender’s take on the twenty-first century as a reference) are tailor-made for each of the character’s personalities and hang-ups. For Claire, phrases like, “Because I’m telling the truth, that makes me a bitch?” and “I have just as many feelings as you do” are a natural part of her naive, spoiled persona. And then there’s Allison (Ally Sheedy, the most underrated Brat Pack member), the goth Hot Topic character, if you will. Her refusal to utter anything for the first half of the film is just as much in keeping with her role as a representation of the “troubled teen” as Brian’s (Anthony Michael Hall) constant need to ramble about various rules and regulations in his position as the “neo-maxi zoom dweebie.”

As for the jock of the group, Andrew Clarke (Emilio Estevez), he has his hands full trying to assert his position as the alpha male as John Bender (Judd Nelson), the “criminal” of the outfit, undermines him at every turn with jibes like, “I don’t think I need to hang around you fuckin’ dildos anymore.” The intensity of the dialogue is compounded by the fact that everything takes place over the course of a day spent in detention on a Saturday (an occurrence that would probably never happen in the current era–because no school official wants to deal with that shit on a weekend). Every outburst, every admission is made weightier by the realization that they’re all confined together in that library. Luckily, Bender’s weed supply eases the tension.

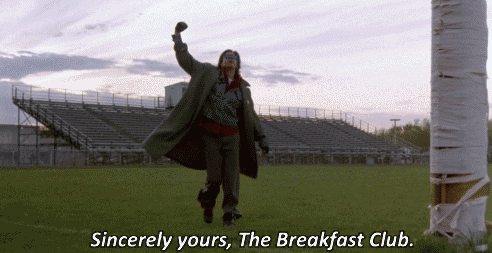

By the end of what amounts to one long therapy session, the five of them, in spite of the different social cliques they hail from, have become friends–and, in some cases, even lovers. Whether or not this development will last through Monday is left to the viewer’s discretion, though one doubts that Claire would just give a diamond earring to Bender and then act like it didn’t mean anything. Then again, she’s got plenty of diamonds to go around. Whatever may have happened to them after that fateful Saturday, each one came to understand something about themselves and, ultimately, the bullshit that characterizes the high school experience. And, more importantly, the teens of subsequent generations still have this movie to turn to during those times when wrist-slitting, home schooling or dropping out seem like more viable options than actually seeing high school through.