In American elementary schools and Alcoholics Anonymous meetings, it is usually a circle of trust that ensures a safe sanctuary among strangers typically and rightfully mistrustful of their fellow human. In Ruben Östlund’s fifth feature, The Square, that premise is instead based upon this eponymous shape (try not to get it confused with the far shittier James Ponsoldt movie, The Circle, from earlier this year starring Emma Watson and based on the Dave Eggers novel of the same name).

For a man who got his start in the world of skiing films, Östlund has come a long way in a short span of time, with my favorite title, The Guitar Mongoloid serving as his first documentary-like feature. Elements of the documentary style occasionally creep into The Square as well, with hyper-real and extended scenes serving to augment our level of discomfort.

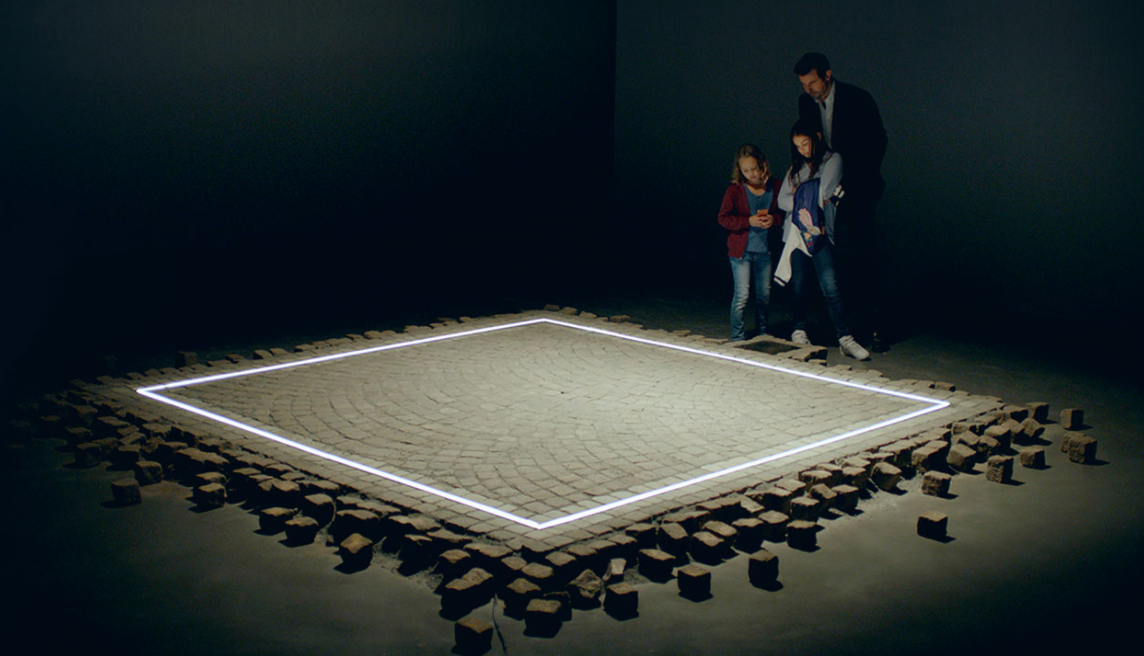

Centered around the day-to-day dealings of Christian (Claes Bang), the curator of a modern art museum called the X-Royal in Stockholm (don’t try to find it because it’s not real), Östlund’s deft, meticulously unfolded script is based upon the simplistic thesis of “The Square” by Argentinian artist Lola Arias: “The Square is a sanctuary of trust and caring. Within it we all share equal rights and obligations.” It’s an almost utopian notion of course, and it might even be too much to expect the people who briefly participate in the exhibit to oblige the requests for help from those who enter the square in the name of “art.”

Meanwhile, the museum has hired a marketing and communications team to help promote the new installation, shedding light on how tainted art has become as it is increasingly commodified and looked upon as a source for profit. That being said, the millennials in charge of coming up with the campaign are trying to find an “angle” (shape pun intended)–some sort of controversy to start an international dialogue. Christian and his co-curators are willing to listen, but have yet to come to an agreement on what said “controversy” could be.

And as the latest exhibit, called very literally “Mirrors and Piles of Gravel” by an artist named Julien (Dominic West), featuring mounds of dirt presented as art, is about to close, Christian’s personal and professional narrative only gets stranger. To accent the message of Arias’ vision of “The Square,” this shape is seen prominently in many scenes, from the framed artwork in Christian’s entry hallway to the abyssal square formed by the winding staircase in his building. Its constant presence serves to highlight the point that in his personal life, Christian does not practice the social consciousness he attempts to preach in his art selections for the museum. For instance, he ends up taking the advice of an employee, Michael (Christopher Læssø), and going to a residential building in a dodgier end of Stockholm (tracked via the old Find My iPhone method) armed with copies of an anonymous and threatening note that demands his stolen items are returned or else. He drops the paper into the letterbox of every apartment, prompting the ire and harassment of a preadolescent boy who insists he will “make chaos” in Christian’s life until he apologizes to him and his family. The final showdown/interaction Christian has with this boy is one that speaks to Östlund’s grand statement about the discrepancy between the individual versus society at large being able to make a difference in our collective perception of “the other”–the social class deemed “icky” because of its poverty.

For as progressive as Christian would like to believe himself to be, it becomes evident to him that there is a disconnect between how he lives and the philosophies he espouses. The art Christian curates is in keeping with his response to a journalist he ends up sleeping with, Anne (Elisabeth Moss, ever expanding her acting range), after she asks him to explain a lengthy, nonsensical statement from the museum’s website. After she reads it to him and he, too, clearly has no idea what’s being said, he offers, “Can I just see that for a moment?,” taking the paper from her to try to interpret it on the fly. What he comes up with is something all too telling of how people will consume anything as art if the context is right: “If you place an object in a museum–for instance, if we took your bag and placed it here–would that make it art?” Anne, not sold as some others would be, hesitantly remarks, “Okay,” not fully wanting to dismiss Christian’s response, as she’s still attracted to him.

Indeed, Christian’s good looks and calmness under pressure (even when his co-worker informs him that a member of the cleaning staff has vacuumed up one of the piles of dirt from the exhibition and should they call the insurance company about it?) affords him plenty of interested women. Except maybe the woman who runs screaming through the square, or piazza, as Italians call it, on his way to work. It seems Christian and another stranger are the only ones willing to help her. And this is precisely what he later realizes the con artists were banking on, the total immunity to crisis of the average passerby, as they end up capitalizing on Christian’s kindness to steal his phone, wallet and even cufflinks.

It isn’t just the hypocrisy of the art world and humanity at large’s alleged desire to help in theory but never in practice that Östlund goes into detail about. The hotbed (no pun intended) issue of sexual assault comes up several times in The Square as well, with Anne demanding of Christian,”How often would you say that you take women who you don’t know very well and have sex with them?” and at last flatly stating, “I think you’re a man who enjoys using your power to attract women as conquests.” Christian cedes to her point eventually, countering, “What’s wrong with admitting that power is a turn-on?” To this point, there is quite a bit Christian seems to be accustomed to getting away with, as evidenced by his behavior after having sex with Anne. “You must think very highly of yourself,” she suggests, as Christian holds onto his sperm-filled condom with a vise grip, as though fearful that if she takes it away, she might impregnate herself with it behind his back.

At every turn, Christian’s actions are at war with his previously claimed philosophy about having a social contract with his fellow human–eventually forcing him to declare at a press conference that his museum and professional life are separate from his life as a private citizen. That Sweden is a country consistently ranked as having the best quality of life is another layer to the film being that, in practically every frame of The Square, there is a “beggar,” as the subtitle sees fit to call them (in America, it’s the slightly more polite “homeless person”).

Östlund doesn’t necessarily paint them as the innocents either, at one point elucidating the inverse of the old adage, “Beggars can’t be choosers,” when a homeless woman at the 7/11 requests Christian orders her a chicken ciabatta “with no onions.” A grim portrait of humanity indeed.

And as Östlund succinctly puts it, a human is merely “a monkey with culture.” That much is clear when a dinner put on for some of the museum’s key patrons and donors featuring the artist from the video installation of a man imitating a primate (played to eerie perfection by Terry Notary) leads to one of the most chilling and lengthy scenes of all. As the “monkey” wreaks havoc upon the room in the name of “art,” bystanders do nothing for a reprehensible amount of time, feeding into the belief that it is easier to disengage from the turmoils of others than get involved. It is, in short, everything that goes against the mantra of the square–that if a human is in need or in pain, we must uphold the unspoken social contract to help them.

But it isn’t all an attack on the nature of humans. There’s, in fact, a very positive scene where Michael gets really excited that Christian has Justice on his playlist, exclaiming, “I haven’t heard Justice in forever,” with the volume to “Genesis” turning up full blast in the car. There’s a deliberateness to that song title, too. As though Östlund is suggesting that maybe we ought to go back to the start to try and get things right again. To practice what is preached. Of course, no one can stay boxed in by a square parameter for very long. Just ask Eve.