It’s not hard for me to admit that I enjoy the films of Woody Allen. He has left an indelible mark on cinema history. But how well his movies will hold up over time as more and more unsettling information about his sordid sexual advances arises is beginning to form something of a question mark. Like Roman Polanski and Bill Cosby, it’s not only a challenge to watch his work without letting the nature of his personal life affect it, but the way women are portrayed is starting to come across as more than a little antiquated and two-dimensional.

While Blake Lively would like to insist that Allen is “empowering to women” based on her recent working experience with him on Café Society, a cursory glance back at his canon of work immediately states the opposite. Apart from the numerous “working girls” and molls that have populated the frames of his films–from Tina Vitale (Mia Farrow) in Broadway Danny Rose to Linda Ash (Mira Sorvino) in Mighty Aphrodite–there is frequently the plucky “little girl” who just wants to please (Emma Stone as Jill Pollard in Irrational Man comes to mind). Woody Allen (and those in his professional circle) has proudly remarked on his ability to “compartmentalize.” It was a skill he wielded with remarkable aplomb while filming 1994’s Bullets Over Broadway and having to deal with the custody battle that ensued after Mia Farrow discovered his relationship with their adopted daughter, Soon-Yi Previn. The ability to shut off one’s mind to certain realities and turn it on to other, let’s say, more false ones is further elucidated by Allen himself in describing the motif of The Purple Rose of Cairo, explaining Cecilia’s fascination with the same movie by remarking, “People are faced in life with choosing between reality and fantasy, and it’s very pleasant to choose fantasy.” Allen ought to know.

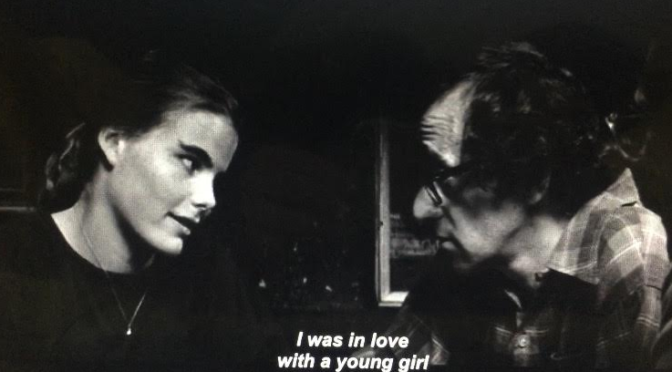

In 2012, before Dylan Farrow reiterated the sexual abuse charges she lodged at Allen back in 1993, when the split between Woody and Mia was in full-tilt progress, an aggrandizing documentary about Allen’s career and directorial methods, called, succinctly, Woody Allen: A Documentary, was released. Directed by Robert B. Weide (whose path seemed determined to cross with Allen’s based on his documentary, The Marx Brothers in a Nutshell, and working on several episodes of Curb Your Enthusiasm), the focus on Allen’s filmography invariably leads to the way in which his personal life bleeds into it, Louise Lasser, Diane Keaton and Mia Farrow all at some point glaring examples of this. Not to mention the constant presence of a much younger love interest thrown into the mix (Manhattan, Mighty Aphrodite, Magic in the Moonlight and Irrational Man providing some of the more pronounced age differences).

The universe that peppers Allen’s scripts consists of two types of women: the neurotic psycho bitch (any character played by Judy Davis or Anjelica Huston) or the easy-going, loose ingenue (Diane Keaton, Mia Farrow, Mariel Hemingway). The most complex female characters Allen has ever rendered to the screen are, arguably, Marion Post (Gena Rowlands) in Another Woman and Jasmine Francis (Cate Blanchett) in Blue Jasmine. Incidentally, each of these characters conjures images of Farrow post-Soon-Yi discovery. Because, yes, “there’s only so many traumas a person can withstand before they take to the street and start screaming.”

As for the mounting, pretty much ironclad evidence to suggest Allen is, indeed, a pervert, the aforementioned retrospectively cringe-worthy documentary offers an interview with Mariel Hemingway in which she politely tries to make herself (and us) believe that Allen was particularly interested in “hanging out” with her off the set so that she would feel comfortable, and that their onscreen relationship would come across as authentic. A few years later, in 2015, she would confess that nothing about their rapport was appropriate. Numerous times in the films of Allen, the auteur has asked–whether in the role he’s playing or through the character of someone else–“Why is there so much suffering?” Stardust Memories poses this question to a group of aliens–perhaps the extent of how Allen can view God. Bizarrely, Allen himself has been the direct cause of someone’s infinite suffering: Dylan Farrow (if that’s truly the only girl traumatized).

But the school of thinking that Allen’s generation hails from is one that views women as curious, sometimes even interesting, experiments that can be silenced when needed. Just take a look at his dismissive, grossly paternal thoughts on his marriage to Soon-Yi. And yet, Allen will never admit to any wrong-doing. Because, in his mind, what he’s done is not wrong. It never really happened–at least not from the “embellished” perspective Dylan is telling it from. He’s chosen fantasy over reality. Which is, I guess, what those who still love his films must do if they want to keep watching them.

[…] too, we could all–all being those still firmly devoted to the Allen canon in spite of certain glaring issues–ask of how we feel about the auteur himself. Sure, those not a part of the “gray” […]