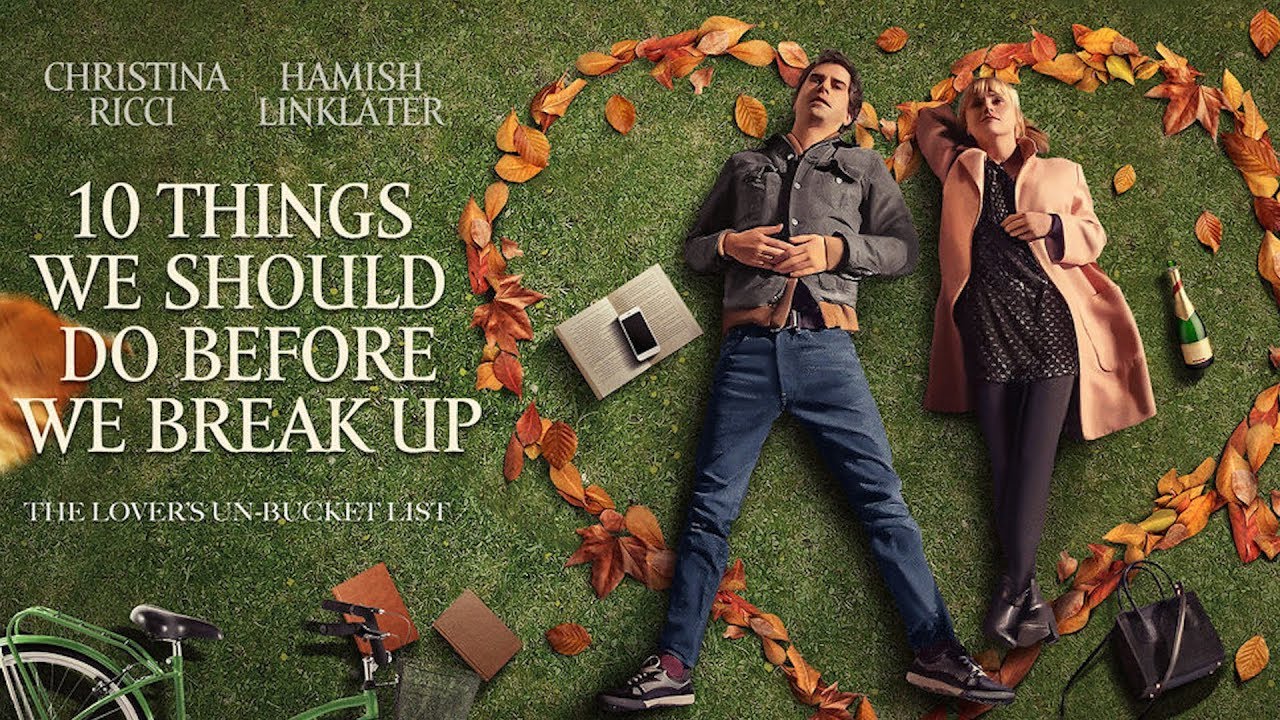

Of course, no couple wants to believe they’re going to be yet another drop in the massive ocean of failed and/or misguided relationships. Some, however, believe so much they’re going to be different that they go so far as to tempt the fates at the outset of their initial “courting period” (if one will pardon that eighteenth century sound of such a phrase). As is the case with Benjamin (Hamish Linklater) and Abigail (Christina Ricci), looking evermore like Reese Witherspoon’s stand-in), two “Brooklyn kids” who meet at a bar after Abigail is lured there by a friend who doesn’t tell her it’s a setup. That’s likely because she knows Abigail is hopelessly stubborn in her single ways and supposedly self-contented with motherhood alone. That’s right, she has two young children, a girl named Wallace (Mia Sinclair Jenness) and a boy named Luke (Brady Jenness–so yes, they’re brother and sister in real life for that authenticity flair).

Yet this is but only one of the ways Abigail and Benjamin are vastly incompatible apart from their similar status as “aging hipsters” living in the parts of Brooklyn where such a demographic gets edged out after finally feeling too pathetic in the likes of Bushwick (for Benjamin, that means living in Bed-Stuy, for Abigail, the more “adult” version of that, Clinton Hill). Where Abigail is responsible and committed to her work from home lifestyle (before it became the “new normal”), Benjamin remains a 38-year-old bar troll who looks like one of those skeevy “regulars” that started coming in their twenties and never got the memo that it was time to pack it in after a certain birthday. The “skulker” who could be just as happy to run into a girl who already happened to be at the bar rather than being set up with Abigail. But he is, and she shows up. So there’s that. As the two get to talking about the inevitability of their breakup if they got together (Benjamin being the one to do most of the prophesying in some neurotic New York way that’s supposed to be “charming”), they decide to come up with a list of ten things to do before that unavoidable fallout—hence the very straightforward title.

Indeed, everything about the movie is straightforward behind its attempt at shrouding “human complexity” (more specifically, so-called “human complexity in Brooklyn”). Written and directed by Galt Niederhoffer (who has worked with Ricci before via 2001’s Prozac Nation), the brevity of the script despite all that happens within such a short time frame is in keeping with the breakneck pace at which the storyline unfolds. One assumes also that Niederhoffer wants that pace to speak to the “New York minute” trope. How multiple lives and unfurlings of drama can happen in said town in the span of mere weeks. How time is not elastic there, so much as a bullet followed by an explosion that leads to some kind of relieving of whatever pressure was being applied.

For Benjamin, the pressure of being a family man—and taking on two kids that aren’t even his—becomes too great after a brief flirtation with the picture of what that would look like. Though, for a time, he goes through the motions with quite a bit (a suspicious amount, actually) of enthusiasm after Abigail tells them one month following their first meeting that she’s pregnant from what was to have been their probable one-night stand. But before that enthusiasm manifests, Benjamin has a cunty meltdown in which he tells Abigail that no man will want her if she has the baby. After all, she’s already undesirable enough with two wannabe Park Slope (for Clinton Hill is one of those wannabe Park Slope/kidcentric neighborhoods) terrors, let alone three. Ready to write him off in that moment, Benjamin does his brand of smooth-talking to get her to forgive him. Then, naturally, they end up banging again and soon the little weasel has burrowed right into her heart. Or so she’s blind enough to believe.

With Abigail’s guard down, she starts bringing Benjamin around the kids more freely. Benjamin even forges a bond with a more grudging and closed off Wallace, who at last falls for his yarn of dependability when he sets up a kiddie pool in their backyard to teach them how to surf. There are many such “heart-rending” scenes as these, including an elapsed time scene of the quartet spending their days together in the harmoniousness of a true “family unit.” Sure, the kids still have their dad and visit him regularly in his own not-to-be-credibly-believed-by-anyone-who-actually-lives-there brownstone in Brooklyn. But Benjamin is their new revered father figure—and all primarily because it’s clear that he’s important to their mother, whom they, naively, trust with all they have. Benjamin shows signs of his inherent skittishness to the scenario at first, but never too much as to not be able to “take it back” or “rein it in,” thus successfully duping someone as emotionally vulnerable as Abigail.

While it’s clear that 10 Things We Should Do Before We Break Up (one version of the cover art doing a send up of 1999’s teen comedy 10 Things I Hate About You) wants to lend further “romantic” flair to the situation by wielding its Brooklyn filming locations for a “picturesque” effect (if bad graffiti and depressing architecture is picturesque to you), it only serves to enhance the bleak loneliness of it all. Including scenes of Abigail and Benjamin biking through the darkened and deserted neighborhood at night, going to Fort Greene Park (where Niederhoffer inserts a shot of the famed Prisoners’ Ship Monument), and waiting at the Marcy stop together with her kids. Regarding that last scene, it’s part of their pre-breakup bucket list: taking every aboveground train in Brooklyn. There’s also getting to second base while in a taxi that’s going over a bridge, reading The Sunday Times in bed together (a very Sex and the City-era idea of New York) and swimming in a deserted pool together. For the latter setting, Niederhoffer, creates a très Michel Gondry à la Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless mind moment as the two lay side by side in a drained square. In a dilapidated community pool that hovers near the river, where, in true “Brooklyn romance” fashion, he takes her on their first “proper” date.

Abigail, in spite of having been failed in a big way at least once before by a man spouting vows of commitment, can’t seem to “keep her eyes open,” as her best friend, Kate (Lindsey Broad), puts it, about what dangers might lie in wait soon down the road. But Abigail is incensed by this warning, this urging that she terminate her pregnancy before it’s too late. Abigail vehemently rebuffs any such notion, insisting that what she and Benjamin have is real, and the it won’t go toe-up even though they’ve ignored all the conventional “safeguards” in place to ascertain whether or not they really like each other—let alone love each other. But “love” is an easy word to bandy about—particularly in New York, where emotions shift as rapidly as trending neighborhoods. One minute you’re hot, the next you’re not. At least, that seems to be Benjamin’s irrevocable approach to women and dating as he keeps flitting casually back and forth between an ex and Abigail.

Alas even “cool moms” of Clinton Hill who create graphic designs and storyboards for children’s books, can’t be so “cool” as to let just any pompous-despite-being-quite-low-brow, self-involved dick waltz in and out of her life merely because the male dating pool in Brooklyn is shallow in general—and as dried up as the one they lay in together when a woman exits her twenties. What’s more, Benjamin doesn’t even offer something redeeming in the personality department—like, say, an even-tempered manner. His moods and emotions “turn on a dime,” as Abigail phrases it, leading them to the foretold downfall by the end of the one hour and fifteen minute affair.

And yet, some viewers were probably daft enough—blindly faithful in matters of true love even in a place as loveless as New York—to believe that, regardless of the very clear-cut title indicating the inescapable, there has to be hope for Benjamin and Abigail in the end. There isn’t. Because what 10 Things We Should Do Before We Break Up addresses is that at the end of every “fairy tale” (even one with a “gentrifier’s” tinge), that’s when it all really starts to go south. The glaring thing they can never achieve on their list of acts to fulfill before breaking up is getting married. And maybe that’s the only “happy ending” element of this neurotic Brooklyn male-spotlighting “love” story: being spared that waste of time.