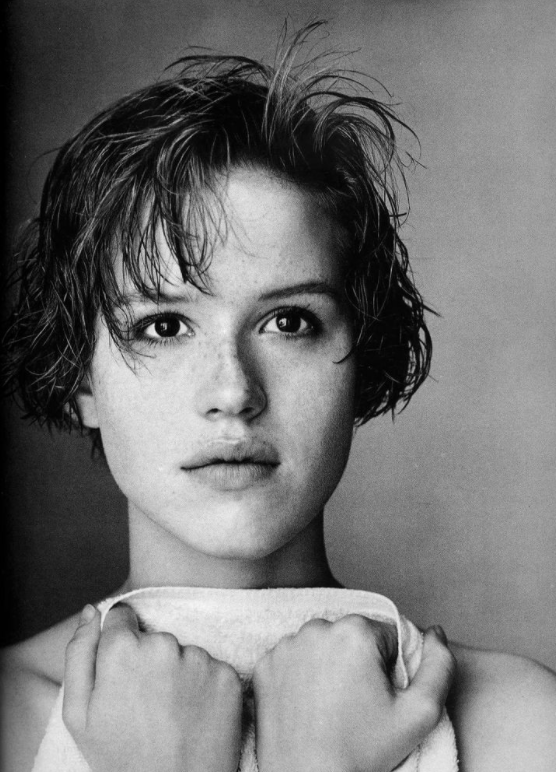

The title “Ain’t She Sweet” in the May 26, 1986 issue of TIME (still endlessly relevant in the 80s) describing the state of Molly Ringwald and her teen queen movie status might have led the public to believe everything in her life was hunky dory, but, beneath the veneer of fresh fame and success was a truth that Ringwald has only just now decided to openly discuss. With the pertinence of Harvey Weinstein and, as of this week, James Toback (both men Ringwald has worked with on films from her oeuvre), Ringwald’s personal essay in The New Yorker, “All the Other Harvey Weinsteins,” which somehow sounds like a perverse reimagining of All the Pretty Horses, is exactly what we need.

In her confessional tone, Ringwald’s voices feels confiding, as though what she’s telling is just to you, her lone reader. What she’s professing to you, to your shock, is that even in her John Hughes bubble of filmmaking and protective parental attentiveness, she was not immune to the abuse of Hollywood. And though she might have narrowly avoided any unwanted advances from Weinstein solely “because of timing. I was in one of the first films that Weinstein produced,” it didn’t mean she wasn’t subject to denigration elsewhere, which she goes into detail about in addition to her experience with Harvey. The film she worked on with him–or rather, for him–was Strike It Rich, and, as a result of Weinstein’s egotistical influence, it ended up nothing like Graham Greene’s source material–not even the title, originally Loser Takes All. Coming off the high of her 80s success, Ringwald was already having trouble transitioning away from anything non-John Hughes related (her last movie, Fresh Horses, co-starring Andrew McCarthy was a critical and commercial flop). Thus, the Weinsteins’ diva-like behavior in spite of only having just gained major traction with Miramax, an independent production and distribution company the brothers founded in 1979, was not helpful.

But Ringwald was still somehow safe since, as she puts it, “…at that moment in time, I was the one with more power. The English Patient, Weinstein’s first Best Picture winner, was still a few years away. The worst I had to contend with was performing new pages that Harvey had someone else write, which were not in the script; my co-star, Robert Lindsay, and I had signed off to do a film adapted and directed by one person, and then were essentially asked to turn our backs on him and film scenes that were not what we had agreed to.”

And this is just the beginning of Ringwald throwing some much deserved shade (perhaps at a level only slightly surpassed by George W. Bush’s recent speech because it was subtler). Almost harkening back to one of her most beloved characters, Andie Walsh in Pretty in Pink, she repackages the line given to Steff when he asks, “I’ve been out with a lot of girls at this school. What makes you so different?” She squints at him as though he might be mentally challenged and returns, “I have some taste.”

Who knows? That’s probably the exact exchange that might have gone down between her and Weinstein had he, at that time, been even more empowered with the unbridled success that would come to him in the mid-90s. Instead, she refers to taste and the not having of it on Harvey’s part by remarking, “I was always a little mystified that Harvey had a reputation as a great tastemaker when he seemed so noticeably lacking in taste himself. But he did have a knack for hiring people who had it, and I figured that’s what passes for taste in Hollywood.”

But no longer. It’s very evident that even if systemic change can’t seem to be made in politics, maybe–just maybe–it can in entertainment. There are far too many women fed up with the treatment they’ve been forced to endure in the name of “getting ahead” while still somehow being behind men.

Now that women are aware they aren’t alone in their tales of horror, it’s going to be a lot easier to band together to break down the final barrier. Like Ringwald said, “I never talked about these things publicly because, as a woman, it has always felt like I may as well have been talking about the weather. Stories like these have never been taken seriously. Women are shamed, told they are uptight, nasty, bitter, can’t take a joke, are too sensitive. And the men? Well, if they’re lucky, they might get elected President.” Side bar: still no word on why that sexual assaulter hasn’t been so much as been threatened with arrest for his actions.

With the entertainment industry being about the only thing Americans will pay attention to with any sort of real vigilance, it’s natural for Ringwald to conclude, “My hope is that Hollywood makes itself an example and decides to enact real change, change that would allow women of all ages and ethnicities the freedom to tell their stories—to write them and direct them and trust that people care. I hope that young women will one day no longer feel that they have to work twice as hard for less money and recognition, backward and in heels. It’s time. Women have resounded their cri de coeur. Listen.” Time will tell if men’s ears are as deaf as is feared.