“We had been married three months and I rather thought it was time to get rid of my wife.” So begins the original story from which A New Leaf was adapted from, “The Green Heart” by Jack Ritchie. It doesn’t exactly scream, “Offbeat rom-com,” but if anyone could make it so, it was Elaine May, who wrote, directed and starred in the film version of the tale of a man eager to kill his rich wife for, what else, her money. As the accident-prone Henrietta Lowell, a wealthy botanist who rarely, if ever, draws the advances of men (much like May herself, of whom Richard Burton once stated, “Elaine was too formidable, one of the most intelligent, beautiful, and witty women I had ever met. I hoped I would never see her again.”), May delivers a charming in its earnestness performance. At first a constant annoyance to spendthrift Henry Graham (Walter Matthau)–William Graham in the short story–Henrietta gradually wins him over with her cluelessness and daffiness despite all his best plots to kill her.

His initial motive for pursuing her in the first place? He’s flat broke after wielding his money with more carelessness than James Dean driving a car. Uncomprehending as his attorney, Mr. Beckett (William Redfield), tells him, “How could I put it? You have no capital, you have no income…you have…no, it’s only money. You have no money. There’s no other way to put it.” Henry returns, “You mean I have no money?” The frustrated to the point of stoicism Beckett confirms, “Yes, that’s what I mean.” The news is delivered with something resembling joy as Beckett despises wastrels like Henry, who squandered his $90,000 inheritance from his father with the ease of elastic waist pants sliding over an anorexic. Being that his wealthy uncle served reluctantly as his guardian for ten years and saw firsthand Henry’s inability to conserve a single cent, it is also unlikely that he would be compelled to lend “a single nickel.”

Fearful of a future without affluence, it is, ultimately, Henry’s butler, Harold (George Rose), who recommends Henry attempt marrying a well-to-do woman in order to uphold the lifestyle to which he’s become so firmly accustomed. It is doubtlessly Harold, in his role as the wise and put upon proletariat, who paints him the bluntest portrait of a life as a pauper, remarking to Henry, “Poor in the only real sense of the word, sir in that you will not be rich. You will have a little left if you sold everything but in a country where every man is what he has, he who has very little is nobody very much. There’s no such thing as genteel poverty here, sir.”

Apart from breaking down the realities of class disparity in America–represented most succinctly by living in New York City–Harold also puts the subject of marriage matter-of-factly by explaining, “It’s the only way to acquire property without labor. There is inheritance, but I believe your uncle has already stated his intention of leaving everything he owns to Radio Free Europe.” Just the thought of marriage makes Henry, a bachelor through and through, cringe, stating “Oh, I can’t, Harold. I couldn’t…I mean, she’d be there…asking me where I’ve been…talking to me…talking. I wouldn’t be able to bear it.” Yet, of course, Harold is right–it’s the only way to acquire vast wealth with little to no work. Even so, he’ll still need a little financial aid from his uncle–$50,000, to be exact, in order to come across as an independent, well-bred man worthy of marriage. So he sells himself as a stock that will only increase in value should Uncle Harry (James Coco) agree to the terms of the loan, assuring, “It’s a better return than you get on any stock.” Harry bites back, “But you are not a stock, Henry. You are an aging youth, with no prospects, no skills, no character. What could you possibly do in six weeks that would enable you to repay me?” Confidently, Harry insists, “Get married.” He balks, “To whom?” Henry plainly states, “Well, I would find a suitable woman.” Eye rollingly, Harry adds, “By ‘suitable’ you mean rich?” To further convince Harry of his viability, he reminds, “As far as marriage is concerned, I do have prospects. I even have skills, to the extent that I’m not physically disabled. I’m reasonably well-mannered. And I can engage in any romantic activity with an urbanity born of disinterest.” Consenting at last to the loan with new terms of loan shark-like usury, Harry is, if not at least confident that Henry can deliver, is confident that he cannot–which would mean a financial win for him.

So he goes about the delicate process of finding the perfect victim. With a few missteps at first that squander precious time on a woman with no money, Henry finally comes upon Henrietta Lowell (May), described as follows: “I think she’s about the most isolated woman I’ve ever met. Rich, single, isolated.” In short, the perfect target. However, as Henry soon comes to find, there’s a reason she’s been left on the market for so long, breaking it down to his butler as follows: “Never have I seen one woman in whom every social grace was so lacking. Did I say she was primitive? I retract that. She’s feral. I’ve never spent a more physically destructive evening in my life. I am nauseated. And I can feel my teeth rotting away from an excess of sugar that no amount of toothpaste can dislodge. I will taste those damn Malaga wine coolers forever. That woman is a menace not only to health, but to Western civilization as we know it. She doesn’t deserve to live.” Henry, realizing he’s let his ultimate diabolical plan out of the bag, corrects himself, retracting his statements with, “Forget I said that.”

But it’s hard to put the plot of murder out of one’s mind. For a while, though, Henry does just that, focusing on the task of pinning Henrietta down, especially after his plot has been unearthed by both Henrietta’s lawyer, Andy McPherson (Jack Weston), and Henry’s own uncle, who so desperately wants him to fail at his agenda. And this is where one of May’s most important and accurate philosophies about women come into play–for only a woman could comprehend just how believable it is for the female sex to be taken in by the right line. In this case it comes in the form of Henry’s explanation for borrowing the $50,000, to which McPherson demands, “Alright. Let’s hear the reason. Now, you were going to use the $50,000 to set up a fund for the disadvantaged and make a better world. Am I close?” Henry, proceeding to lay it on thick, refutes, “No sense in being facetious, Mr. McPherson. I was going to use the $50,000 to tidy up my affairs and then immediately afterwards kill myself. Yes, Henrietta. On the day I met you I was a dead man. My life was over. And then something happened to me. I suddenly realized that if by some miracle I could have you I would have a purpose, an answer to the emptiness of my existence. And so I proposed, Henrietta. Not to get your money but to find out if I had a reason to live.”

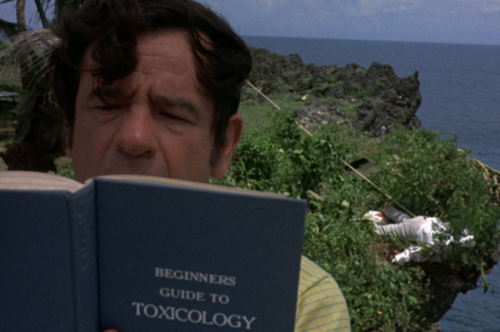

Naturally, Henrietta eats up this falsity like a gourmet dessert, for there’s nothing a woman wants to believe more than that she’s desired in such a way and has that powerful of an effect on a man. So it is that Henry easily enters into marriage and Henrietta’s Estate, both literal and figurative. And on that estate he discovers that many others have been taking advantage of Henrietta’s guilelessness as well, from the head maid to the chauffeur–everyone’s been capitalizing, and in cahoots with McPherson no less. Henry ends all of that with the seriousness of his death threats to the staff. The William Graham of the short story, believe it or not, is actually much more ruthless in his machinations, going so far as to poison two people on his path to getting his wife right where he wants her: vulnerable as possible for the kill. Henrietta, in her cloud of love and the search for a new species of plant that will immortalize her in name, doesn’t notice Henry’s flagrant reading of Beginners Guide to Toxicology on their honeymoon or his “subtle” references to her not being around much longer.

As one of the few modern “bluebeard comedies,” A New Leaf‘s uniqueness is evident from the outset with a male character so unapologetically self-involved and self-centered that it makes the faux contrite “emotionally in touch” protagonists of today look even more enervated in comparison. Both a reference to Henry changing his ways and Henrietta’s passion for botany, A New Leaf is one of those rare instances of a film perhaps having a better name than its original source material (this, of course, certainly wasn’t the case with Froth on the Daydream being changed to Mood Indigo). The outcome of the story, in both cases, is a testament to the influence a fondness can have over a man. That of the “I’ve grown accustomed to her face” variety. Do they need these women? No. But now that she’s been had, he can’t imagine not having her around.