Immortalized by white men after N.W.A. already provided the cannon fodder of any protest against police brutality in 1988 with “Fuck Tha Police,” Sublime’s “April 29, 1992” (or, sometimes, “April 26, 1992″) was released four years after the eponymous events surrounding the date and title. The lyrics–peppered with real police radio dialogue from the time–speak not only to the riots that took place in the wake of footage of Rodney King beaten by the LAPD, but how an incident such as this is so often a catalyst for “rioting” (or “protesting,” if you’re white). How it invokes the rage of decades’ and centuries’ worth of repressing one’s emotions and sense of injustice for the sake of “keeping the peace.” But as has become the mantra of the protesters of the present, there can be no peace without justice. And it seems the only way to get it is by using the same level of violence the police are so accustomed to enjoying without ever being checked for it. Certainly not by the letter of the law.

The looting that runs parallel to the escalation of chaos stemming from the anarchic violence is one of the ways in which everything builds to a crescendo, often having nothing to do any longer with the original cause at hand. It’s simply all-out, undiluted rage manifesting in any and every way possible. Frequently, it is those (not necessarily black) who are seeking to capitalize on the pandemonium–having little concern for the principle people are fighting for–that take advantage of the loophole. The wrinkle in protest time that finds law enforcement in too vulnerable a state to bother with making arrests that relate to the pillaging and thievery. So it is that Bradley Nowell speaks on his own white man’s privilege in being able to profit from the backs of the disenfranchised as he sings, “They said it was for the black man, they said it was for the Mexican/And not for the white man/But if you look at the street, it wasn’t about Rodney King/It’s the fucked up situation and these fucked up police.”

It bears noting that the Rodney King Uprising (as it is alternately referred to) wasn’t set off when the footage was unveiled to the public, but rather, when the police who beat him (though, unlike George Floyd, thankfully did not manage to kill him) were acquitted of charges against them citing use of excessive force. Again, the black community waited patiently for “justice” to be served before resorting to taking to the streets. It was, of course, not. The George Floyd Uprising, instead, has set off an entirely different nerve center of resentment. For it iterates the well-known phenomenon of all police very literally being in possession of a get out of jail free card not just for physically harming black people, but for killing them as well. No longer willing to accept this, the riots of 2020 have been borne of the same tensions that boiled to the surface in 1992.

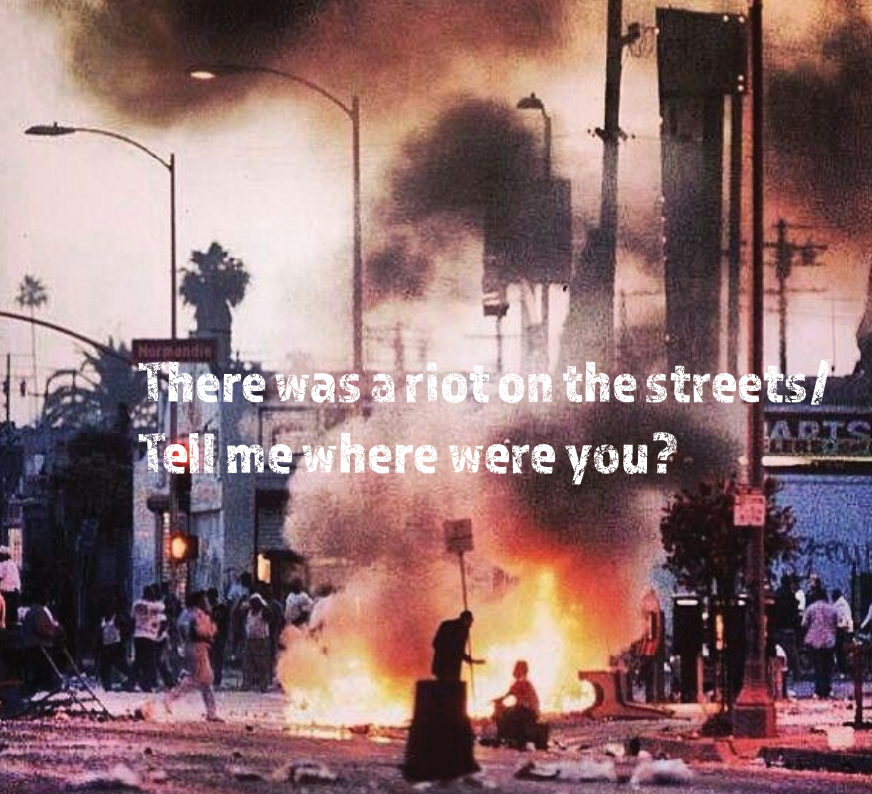

In perhaps a typical white man’s gloss-over of facts, Nowell opens with mentioning the wrong date as he sings, “April 26, 1992/There was a riot on the streets, tell me where were you?/You were sitting home watching your TV/While I was participatin’ in some anarchy.” While, in the present context, the line about certain people being at home watching the broadcasts comfortably from their perch of complacency could be interpreted as shade, in actuality, it was more about the advent of 24/7 live news coverage that first became prominent in the early 90s. As a result, the high drama and intensity of the riots felt all the more palpable to those who had previously never witnessed such unbridled carnage infiltrate their bubble of white privilege.

As the song interweaves the thread of Nowell, his band members and many others seizing on the looting opportunity (à la New York blackout of ‘77) with the injustice of cops continuing to get away with the murder and physical abuse of black men, he charges, “Homicide, never doin’ no time.” Which is precisely why those who have waited patiently for “legitimate” justice can no longer do so, as it’s never delivered from “on high” by the courts, the police chief or the very system that promotes the scot-free existence of white men. The fact that so many “hiding in plain sight” racists join the police force should be telling that it is an institution that has, for too long, been a breeding ground for hate and discrimination to be unleashed on those who never stand a chance to “make it” in the first place thanks to the systemic racism that has been inbuilt into American life since the days of “Reconstruction.” If it can even be called that. For all it did was serve to placate ex-Confederates in allowing Southern states to determine for themselves what the rights of “freedmen” should be.

Abraham Lincoln, of course, had no say in the Reconstruction because he got popped in the head by Confederate sympathizer John Wilkes Booth, still holding out hope for the Confederacy to prevail, which, clearly it did. And largely due to Lincoln’s vice president, Andrew Johnson (the first and only other prez before Trump to be impeached), being so appeasing to the Southern Dems who reverted right back to their old behavior, treating freedmen as subpar human beings the same way they did when they were enslaved. In the modern world, the enforcers of that systemic abuse of power that the Confederates were assured during the Reconstruction has manifested into the po-leese. Which is why Sublime agrees with the Snoop Dogg/Dr. Dre sentiment of “screaming 187 on a motherfuckin’ cop”–187 being the CA penal code for murder.

Nowell concludes the track with a naming of the various cities where riots have taken place, as though seeing into the future of the simultaneous ones that would occur throughout all the U.S. in the wake of a wave of racist occurrences (including the gunning down of Ahmaud Arbery in Georgia and a white woman in Central Park threatening to call the police on a black man doing absolutely nothing wrong save for telling her to leash her dog).

Alas, what perhaps makes the song so persistently pertinent more than anything is the fact that those who have nothing to do with the riots–who do not truly understand being driven to that level of apoplexy–manage to make it about them, to use it in their favor while also somehow making the black community look worse in the eyes of their unempathetic oppressor. Accordingly, Nowell describes, “When we returned to the pad to unload everything/It dawned on me that I need new home furnishings/So, once again, we filled the van until it was full/Since that day, my living room’s been much more comfortable.” Glad to know it can be more comfortable for a blanco while still a fucking nightmare in the aftermath of it all for a black person.