In the spirit of appropriate things released in time for Father’s Day Weekend, can there be anything more “dad rock”-oriented at this point than Bob Dylan? A man who, after six years of no new material, has seen fit to come out of the woodwork with his thirty-ninth album (goddamn). Of course, because everything seems to be about age these days (from who coronavirus was originally meant to be the most hazardous toward to Gen Z blaming baby boomers for all their woes), it can’t be helped to remark on Dylan’s own advancing one. As of May 24th, he is seventy-nine years old.

A fellow icon of the Dylan era, David Bowie, was but a mere sixty-nine years old when he died in January 2016 (establishing a major portent for the rest of that year), released to coincide with his birthday on the 8th. Two days later, he was dead. Unbeknownst to the public, he had been suffering from liver cancer, which, if one listens to the album, is written all over it. From the lyrics to the sense of sonic doom, Blackstar is, in every way, Bowie’s “death record.” It feels rather the same for Dylan’s Rough and Rowdy Ways. For, from the opening line of the first song, “I Contain Multitudes,” he makes the announcement, “Today, and tomorrow, and yesterday, too/The flowers are dyin’ like all things do.” And, as if Lana Del Rey needed yet another reason to splooge over her idol, the title of the song is taken from the famed Walt Whitman poem, “Song of Myself,” in which he states, “Do I contradict myself? Very well then I contradict myself (I am large, I contain multitudes)”–which also happens to be the bio of Del Rey’s Twitter account.

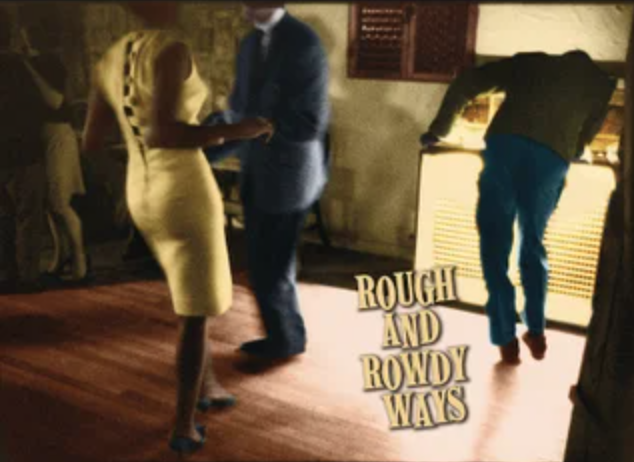

Dylan has been both contradiction and complete cliche in his day, with this latest record being completely in keeping with the style and themes of those from his proverbial “glory years.” In those times, he sang all about change and unrest. To this end, it’s also appropriate that Rough and Rowdy Ways was released on Juneteenth (though nothing was more appropriate than “Black Parade“), for it’s been said that all the things Dylan was writing about in the 1960s were, in fact, based on the the era of the Civil War, a subject that has more relevance than ever in spite of that war taking place 155 years ago (not really long enough to have stamped out the residual racist sentiments of the Confederates and their ancestors). Dylan’s fascination with the era seemed to stem from both its lack of being taught in the schools of Minnesota, and the fact that it became a more prominent source of the intrinsic divide he encountered after heading to the East Coast. In Chronicles Vol. 1, Dylan would say of Robert E. Lee (at the forefront of statue controversy in the present), “It was on his word and his alone that America did not get into a guerrilla war that probably would have lasted ’til this day.” His sympathies for the Southern Confederates have kept him surprisingly from being “cancelled” (for it’s likely that the generations capable of cancelling aren’t aware enough of him). And it’s even been said that Dylan has “borrowed” heavily from a Confederate poet named Henry Timrod for his work.

This fascination with the discord of the 1860s and the decade leading up to it fit in easily with the tumult of the 1960s (already paralleled to the former epoch because of the Lincoln-Kennedy assassination connections). Indeed, it made Dylan a so-called prophet of the era. A notion he seems to address sardonically on “False Prophet,” blasély noting, “Well, I’m the enemy of treason/An enemy of strife/I’m the enemy of the unlived meaningless life/I ain’t no false prophet/I just know what I know/I go where only the lonely can go.” This last part a nod to Roy Orbison, one imagines, for the only person who’s a bigger fan than Dylan is David Lynch. This fandom in keeping with Dylan being forever ensconced in the culture of his own time, an ironic fact when taking into account that the turmoil of said period has served him well for songwriting resonance in multiple decades. He can’t help it if he unwittingly speaks the truth for all generations (even those refusing to recognize the validity of so-called “boomer wisdom”). That’s just the pure “luck” of every age bearing its decided qualities of shittiness. The sound of the bluesy, guitar-laden track is a siren call to dads everywhere, the type of track you could envision being played at a honky-tonk or dive bar filled with old men resigned to accepting their age and the nonchalant jadedness that comes with it. On a side note, it also could have served as one of the offerings on the Dennis Quaid/Julia Roberts-starring Something to Talk About. It just has that banal, white bread feel.

Which is why it’s a good thing he gets back on track with the moody and arcane “My Own Version of You.” Laden with the aura of mysteriousness that stems from a cautious string arrangement, the narrative of the song is a Frankenstein-inspired one, yet also, once more, evokes the death imagery that might very well foreshadow his own as he croons, “All through the summers, into January/I’ve been visiting morgues and monasteries/Looking for the necessary body parts/Limbs and livers and brains and hearts/I’ll bring someone to life, is what I wanna do/I wanna create my own version of you.” While, sure, it could be a statement on the “Mary Jane’s Last Dance” concept of necrophilia being the only way to really get what you want out of a person, it’s also as though Dylan is speaking to himself, wanting to start anew with a version of himself that no one can try to interpret or classify. Maybe simply wanting to begin again as an improved version of himself, in addition to remaking all of humanity into more intelligent, less roguish arseholes–with their “rough and rowdy” ways.

The thread of death persists with a title like “I’ve Made Up My Mind to Give Myself to You,” which seems more a reference to “the other side” than any one person in particular. Sounding like Leonard Cohen (who also died in 2016 after releasing one final album, You Want It Darker) doing an imitation of Bob Dylan, the roving vocals of our Nobel Prize winner explore thoughts of traveling “a long road of despair/I met no other traveler there/Lot of people gone, lot of people I knew/I’ve made up my mind to give myself to you/I’ve seen the sunrise, I’ve seen the dawn/I’ve traveled from the mountains to the sea/I hope that the gods go easy with me.” If that’s not a song of surrender to the reaper, one doesn’t know what is.

And, talking of old Grimmy, “Black Rider” seems to be all about him, or, specifically, trying to evade him a little while longer, in classic The Seventh Seal fashion. So it is that Dylan bargains, “Black rider, black rider, all dressed in black/I’m walking away, you try to make me look back/My heart is at rest, I’d like to keep it that way/I don’t wanna fight, at least not today.” Commencing with its mafioso, The Godfather-esque strings, Dylan’s (especially) rasping voice throughout the track seems an intentional complement to the nature of a song that seems to be entirely about negotiating for more time, finally concluding with, “Black rider, black rider, hold it right there/The size of your cock will get you nowhere/I’ll suffer in silence, I’ll not make a sound,” as though at last capitulating to the dogged bastard.

A tribute to a blues singer would be nothing without the signatures of the genre. So it is that “Goodbye Jimmy Reed” is in keeping with the old white dad vibes of “False Prophet,” replete with harmonica solo to really conjure all the fading boomers to the dance floor. Ironic, of course, considering that the “black music” said generation danced to still somehow didn’t incite them to rebel against segregation and discrimination sooner. But hey, why bother when it was easier for the likes of Elvis to simply graft the material? Among the grosser lyrics are: “Transparent woman in a transparent dress/Suits you well, I must confess/I’ll break open your grapes, I’ll suck out the juice,” but then perhaps Dylan was being too tame this whole time with regard to reminding us that he has a sexuality.

Going back to his Leonard Cohen-doing-an-impression-of-Bob Dylan voice for “Mother of Muses,” the gentle opening lulls us into submission with its Greek mythology-drenched homage to the proverbial muse (he specifically calls out Calliope at one point). Still tapping into his after all these years, it’s as though Dylan is expressing gratitude that she has continued to inspire him this late in the game, though he is likely acknowledging that this could very well be the last time, at least in terms of churning out another record. In the spirit of Homer’s The Odyssey, Dylan urges, “Mother of Muses sing for my heart/Sing of a love too soon to depart/Sing of the heroes who stood alone/Whose names are engraved on tablets of stone/Who struggled with pain so the world could go free/Mother of Muses sing for me.” And, of course, Dylan also manages to bring up the Civil War again by name checking William Tecumseh Sherman (a Union Army general), while also interweaving another icon of his own musical heyday (the one in which he wielded Civil War imagery to stoke the flames of dissent), Martin Luther King, somewhat egregiously noting that, among these generals such as Sherman, was “cleared the path for Presley to sing/Who carved the path for Martin Luther King.” Again, it’s moments like these when Dylan can thank his lucky stars that Gen Z don’t give a what about him.

The old white man still playing in his blues band from many moons ago effect is once more present on “Crossing the Rubicon,” along with his history buff tendencies as he croaks, “I crossed the Rubicon on the fourteenth day of the most dangerous month of the year/At the worst time, at the worst place/That’s all I seem to hear.” The fourteenth day of the most dangerous month of the year could refer to myriad events, but among such notable dates is the assassination of Abraham Lincoln on April 14, 1865–because the Civil War nods must abide. At the same time, the track overtly pays tribute to Julius Caesar, through the lens of men of adventure finding their own way to cheat death as Dylan sings, “I can feel the bones beneath my skin/And they’re tremblin’ with rage/I’ll make your wife a widow/You’ll never see old age/Show me one good man in sight/That the sun shines down upon/I pawned my watch, I paid my debts/And I crossed the Rubicon.”

The penultimate track, “Key West (Philosopher Pirate)”–again Del Rey can feel giddy she has a further connection to Dylan with her own “Florida Kilos”–returns to his roaming bard sound (the one he ought to stick with instead of all these intermittent attempts at blues in between). Setting up the motif that saturates “Murder Most Foul,” this tale opens with an allusion to the assassination of William McKinley (because, as has been made clear, Dylan finds the past most pertinent to resonating in the present). Thus, Dylan paints the picture, “McKinley hollered, McKinley squalled/Doctor said, ‘McKinley, death is on the wall/Say it to me, if you got something to confess’/I heard all about it, he was going down slow.”

Freshly implying his own awareness of imminent death through that of McKinley, Dylan additionally offers, “If you’re looking for immortality/Stay on the road, follow the highway sign”–suggesting, perhaps, that it can be achieved when one is still heard over the (pirate) airwaves that trickle into people’s homes, the collective consciousness. The frequent use of the symbol of a flower–so prone to representing the cycle of life as they bloom and wither–is also wielded in the form of: “Hibiscus flowers, they grow everywhere here/If you wear one, put it behind your ear.” Capping off his potential final opus, it’s only natural that Dylan should pull out the big guns with the epic “Murder Most Foul.”

Clocking in at just under seventeen minutes, this boomer ballad (ballad in the poetry sense) not only centers on the assassination of Kennedy, but also the themes of disenfranchisement and decay that befell the United States almost immediately after, as though something in the spirit of the nation died along with Kennedy when he was struck down in his prime, just as America was–on the brink of hopeful change, before it all turned to shit by the late 60s. The last time the civil rights movement was as violent as it has once again become in the present. This, our apocalyptic year of 2020. And that an apocalypse connotes the end of a way of living as we once knew it, well, that just serves as further evidence that Rough and Rowdy Ways could be Dylan’s swan song. After all, a man can only remain trapped in the past for so long (most evident on the album cover) before he reconciles that his place does not reside in the future. Unless, of course, that future is to join Bowie on Mars.