While New York City might have been the town deemed “America’s seediest” in the 1980s, one shouldn’t overlook just how much Philadelphia lived up to that reputation at the time as well. A prime case in point is the retroactively historical document that is Brian De Palma’s 1981 film Blow Out. From the moment we see the industry Jack Terry (John Travolta) works in (making glorified porno material posing as slasher flicks), we’re pulled into the nonchalant underbelly of Philadelphia. An underbelly Jack makes it clear he’s used to after telling his love interest, Sally (Nancy Allen), that the reason he ended up as a sound guy stemmed from being a wiretapping aficionado for the government.

After a botched surveillance operation backed by a group of political officials called the King Commission, the attempt at sussing out corrupt police officers in Philadelphia doesn’t quite work out as Jack hoped. Because unfortunately Freddie Corso (Luddy Tramontana), one of the best officers on the force, was enlisted to have a wire put on him so they could set up a corrupt police captain trying to shake down a mobster for some more bribery money (some peak Philadelphia shit). What Jack didn’t account for was Freddie getting so nervous and sweating to the point where the wire would start burning a hole in his skin. At which time, he exits from the car asking to “take a piss,” sealing his fate by way of the mobster’s suspicion.

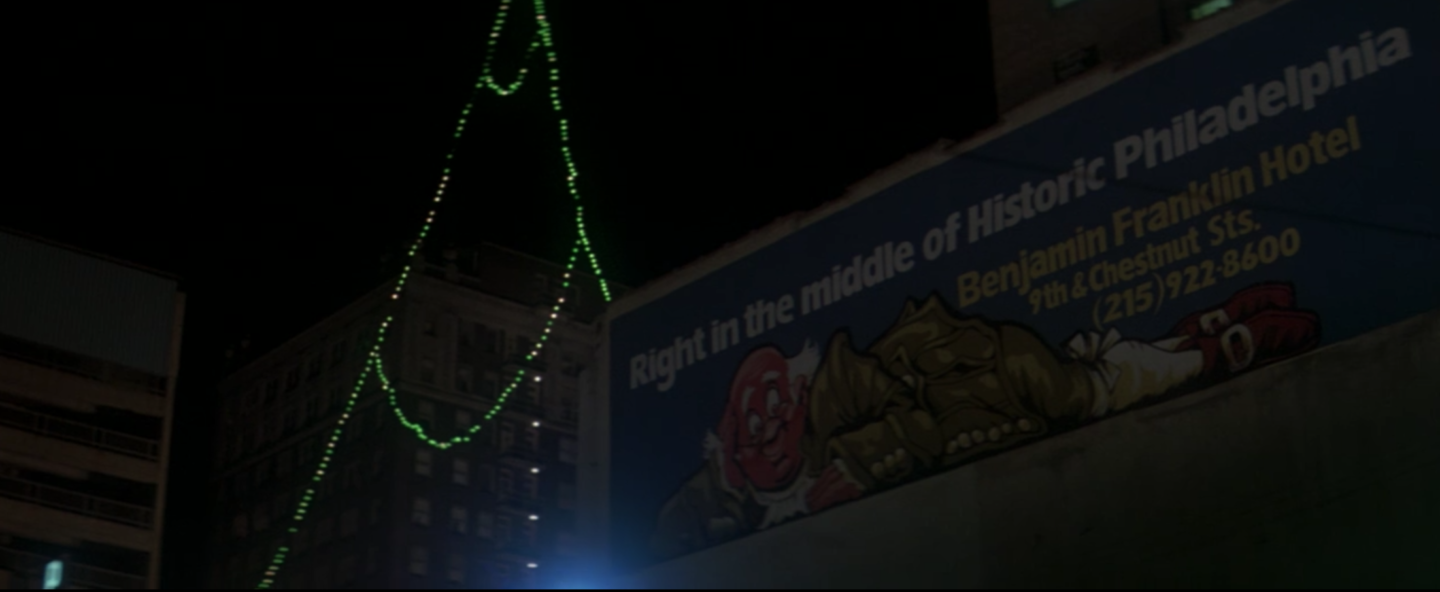

It’s throughout this entire flashback that we start to fully understand that the smallest of details lend additional flair to getting a portrait of the city. Like a shot of a banner in the nearby parking lot that reads: “Right in the middle of Historic Philadelphia. Benjamin Franklin Hotel. 9th and Chestnut Streets. (215) 922-8600.” An image of Ben Franklin—the city’s ostensible mascot—posing like some kind of reluctant pinup rests beneath the typeface. As the camera pans down, we see The Eagle II Restaurant, a since defunct diner that was characteristic of the many late-night eateries that once populated Philadelphia before it became more button-down in its attempt to better emulate the bouge-ified vibe of its competing nearby neighbor, NYC.

And, talking of bouge-ified, the spot where Jack sees the aftermath of Freddie’s murder when he stops into a bathroom to adjust his compromised wire is much more “polished” today. No sign of the Lisbon Madrid Restaurant anymore, but there is a Rite Aid on the block where it was filmed: E. Passyunk Avenue at S. 5th Street. As Jack concludes the story he’s unfolding to Sally, Burke (John Lithgow), the dastardly villain constantly at large in the film, is scouting Sally by referring to a photo from Manny’s (Dennis Franz) pile of blackmail options. Seeing a woman on the escalator he’s certain is her (because, after all, the “trash-whore” look is still pretty common in Philly even today), Burke pursues her from Reading Terminal (which closed in 1984) and into Reading Terminal Market, where De Palma suggestively showcases the word CLAMS in blue neon. In fact, the pervasive neon lights De Palma focuses on become like a calling card of the tableau’s entire sinister aura. For if we’re taught anything by cinema, it’s that the places with the neon lights are the ones signaling decay and depravity.

Burke then follows the woman he thinks is Sally out to the bus stop, showcasing just how much this form of public transportation is at play in Philly. The stop the unwitting decoy tries to board at is Market Street and S. 11th, not knowing the reaper has other plans for her as Burke snatches her by the neck with his choking wire as everyone around them appears utterly oblivious. They fall into a construction site—what would eventually become Aramark Tower before its name later changed to Jefferson Tower. Incidentally, Reading Terminal closed in ’84, the same year this building’s construction would be completed.

As Jack delves deeper into his conspiracy free-fall, his apartment at 323 Arch Street serves as an important location for him to gather his thoughts—and his materials. The ones that will form a homemade movie he’s put together of the blow-out he witnessed from his perch at Wissahickon Memorial Bridge. While trying to pick up some garden variety wind sounds for the slasher movie he’s working on, Jack doesn’t bank on also picking up the sound of the gunshot that blows out Governor McRyan’s tire, sending him over the bridge and into the water with Sally in the car as well. The cutthroat, sordid nature of both the city itself and its politics manifesting in this conspiracy-laden moment.

Being that Philadelphia is considered, in so many ways, the birthplace of America and its purported principles, still rife with all the historical documents to prove it, it feels as though De Palma chose the town for the benefit of highlighting the irony of our corrupt system. The very system that swallows anyone who goes against it whole. Scenes of Jack eventually barreling through City Hall on the “Liberty Day” celebration (a parade in honor of the Liberty Bell) are indicative of the futility in going up against the behemoth—the Hydra—that is government.

Not wanting to give Reading Terminal all the action on the public transportation front, 30th Street Station, where Sally is lured into a meeting with Burke, will also play a key role in the film’s iconography, as well as how this location steers the plot forward to its final denouement. It is after realizing Sally’s been set up at this meeting point that Jack drives through City Hall and ends up crashing into a display window at Wanamaker’s Department Store—now a Macy’s.

Coming to in an ambulance in front of Independence Hall, Jack tries to get himself together long enough to reestablish Sally’s location. He at last sees her atop the Independence Seaport Museum, crying out a final few times for him. But when he arrives at the spot, it’s too late for Sally. And even though he manages to kill Burke, there is no sense of justice felt as the fireworks display explodes around him. Not letting freedom ring.

And so, if Blow Out unveils anything apart from the act of trying being a lost cause, it’s that De Palma might have been born in Newark, but everything about the film’s ease within the confines of Philadelphia reveals he was raised there.