It’s something few directors can do—keep a viewer engaged throughout a long, meandering story that ultimately brings one back to the start. The start, in this case, being that initial attraction is real. Specifically the magnetic pull between Gary Valentine (Cooper Hoffman, emulating Michael Gandolfini by essentially standing in for his now-deceased father) and Alana Kane (Alana Haim). At fifteen years old, Gary is much more “worldly” than your average boy of this age, what with being a child actor. Though presently caught somewhere in between the boy and man phase (hence casting agents becoming more skeptical). While Gary is based on Gary Goetzman, who did star in the 1968 movie, Yours, Mine and Ours—changed in Licorice Pizza to Under One Roof (with Lucille Ball becoming “Lucille Doolittle” [Christine Ebersole, who probably does a better version than Nicole Kidman])—Alana was based pretty much entirely on Alana Haim.

To promote Under One Roof in 1973, Gary goes to New York with his fellow cast members, including Lance (Santa Clarita Diet’s Skyler Gisondo, who actually looks more like Gary Goetzman than Hoffman). It is his mother, Anita (Mary Elizabeth Ellis), who ends up doing him a favor by flaking out on chaperoning because it gives him a chance to ask Alana to come along instead. After having already shared dinner together at Gary’s usual haunt, Tail o’ the Cock (the Frank & Musso’s of this movie), Alana was adamant in reminding him that their relationship could only ever be strictly platonic. Of course, Gary has already informed his brother, Greg (Milo Herschlag), that he’s met the woman he’s going to marry. In this regard, Gary’s youth is key to the motif of the film, which highlights the unique specificity of first love—and the intensity with which it hits.

As for Alana, who says she’s twenty-five but is actually twenty-eight (as we discover when she briefly lets it slip out at one point), she has the kind of youthful aimlessness that makes her simpatico with Gary more than another woman her age might be. Or Gary’s age, for that matter. And yet, because of social taboos, especially when it comes to being an older woman with a younger man, Alana is consciously resistant to all “the moves” Gary tries to put on her. This even includes starting his own waterbed business (something Gary Goetzman also did) to ultimately both “impress” her and get her to leave her middling, dead-end job as a photographer’s assistant at one of those studios whose bread and butter is school picture day. Indeed, this is the setting where Alana meets Gary, the only person who is actually nice to her amid a sea of asshole kids.

As Alana Haim interprets the day of their encounter, “When Gary and Alana meet at [his school’s] picture day, they don’t know yet their lives are forever changed. And the obstacles they have to go through in life—where the universe is pushing and pulling them constantly—they realize that their friendship and their connection [means] they can overcome the obstacles better together than they can alone. They might try to separate. But they’ll always come back together.”

This idea also pertains to a common Anderson motif that crops up again and again in his work: there is no fighting the Fates. We’re all Destiny’s bitch in the end, and every time we try to combat her, it only ends up making things more difficult and painful.

And yet, Alana is sure throughout the duration of Licorice Pizza that it would be more painful to try succumbing to any of her more-than-platonic feelings toward Gary. Cause more harm and trouble than it would be worth. As she listens to him give his sales pitch at that first dinner at the Tail o’ the Cock, he explains of his acting predilection, “I’m a song and dance man.” A bombastic way to say he’s a con artist who knows how to work a room. Some might even be jaded enough to say he’s working Alana in the hope of getting some action, but there seems far more to it than that (even if Alana later finds out he’s had his fair share of “handies” from older women).

Because the time in which Licorice Pizza is set is as much of a character as it was in Boogie Nights, the oil embargo that OPEC placed on countries like the U.S. in ’73 is a primary factor not only in cutting Gary’s waterbed business short (the bed, after all, being made of vinyl), but also the overall sense of scarcity and “end of days” quality to Southern California, so driven (no pun intended) by the automobile as it is. In this sense, too, Anderson seems to want to highlight the idea that, in every era, the masses had a feeling of the world ending. Except, in this one, it’s actually real. Because, you know, glaciers melting.

With regard to the time and place Anderson focuses on, there’s something Tarantino-esque about this particular film. Likely the blending of real L.A. history with fiction, of the same variety that occurred in 2019’s Once Upon a Time in Hollywood. For Anderson, the characters he chooses to give his own revisionist spin to are more obscure, like Jon Peters (Bradley Cooper) and Joel Wachs (Benny Safdie). The former gives something of a Tom Cruise in Magnolia performance where freneticism and hyper-douchebaggery collide.

Another such collision that occurs in the character of Jack Holden (Sean Penn), whose last name gives the audience the correct assumption that the character is based on William. Alana is eager to accept his dinner invitation while in an “off” phase with Gary and after having auditioned for the part of “Rainbow” in one of his movies. At a certain moment during their outing (during which he unsurprisingly does most of the talking), she asks, “Is this real or are these lines?” It’s always a fair question to demand anywhere within close enough proximity of Hollywood. And what with Alana only freshly trying to break into acting herself with the help of Gary’s agent, Mary Grady (Annette Bening lookalike Harriet Sansom Harris), it’s no wonder she’s confused by the blurred line between fantasy and reality.

The realism that develops amid a cartoonish sort of Anderson style is most notable in the small things made grandiose. Like Alana falling off the back of Jack’s motorcycle before he does a public stunt and Gary running to her eagerly and dramatically to make sure she’s okay. It’s yet another instant where we think this might finally be the time when both give in to their feelings and at last share a kiss, but no, it is still kept strictly Bollywood—the sexual energy always just barely about to burst to the surface. In a way, it obviously couldn’t with another movie genuinely from the 70s: Harold and Maude (released in 1971).

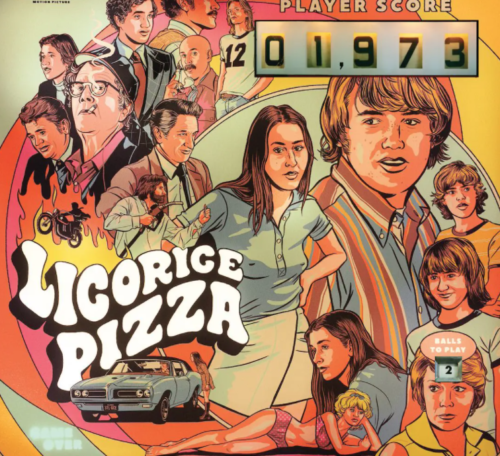

Licorice Pizza (with a movie poster that looks rather similar to the aesthetic style of Harold and Maude’s) seems to be the more “grounded-in-realism” angle to the May-December romance phenomenon that so rarely happens between a woman and a boy (unless you are Madonna, who clearly loved this movie). And yes, Gary shares the same enthusiasm for Alana as Harold (Bud Cort) for Maude (Ruth Gordon). Except he has the sense to later put on more artifice about how he could be “just fine” without her as well.

“You’re not cooler than me,” she reminds Gary at a peak in their contention. It smacks of fellow L.A. woman Lana Del Rey singing, “Well my boyfriend’s pretty cool, but he’s not as cool as me.” Alana Haim herself has the “coolness” Anderson wanted for this role (writing it specifically for her). What’s more, Haim is an SFV girl, claiming her first job as working at Crossroads Trading Co. and frequenting the likes of local haunts Art’s Deli, Pagliacci’s on Ventura (RIP) and Casa Vega. In one interview, she even mentions her love of the Studio City Car Wash, with the iconic giant hand holding a car. So if anyone can get into the skin of a character that’s a product of this milieu, it’s her. Even the fact that her mother, Donna, won as a contestant on The Gong Show speaks to the family’s innate “L.A. running through my veins” vibe.

Despite being a California girl, Haim, who also claims to be a terrible driver, actually had to go to truck school to learn how to drive a stick for what has since become one of the most memorable scenes in recent cinema history (driving-related or otherwise). As for her ability to overcome her fear of performing such a daring feat, it all boiled down to her trust in Anderson, who has been circling the Haim family in some form or other for decades in that the Haim sisters’ mother taught him at the Buckley School (oui, c’est bouget).

The West Coastian sensibility of Anderson coalesces quite seamlessly with Haim and her family’s own. What’s more, there is noticeably no big “play-up” of going to New York and “what it means” when Alana is asked to chaperone his trip. In fact, when they go there, no scenes of them roaming the streets seeing familiar landmarks of that town connoting “romance” ensue. Both seem more contented in the SoCal bubble. Perhaps another primary ingredient to their connection. As for Haim’s status as a distinctly SoCal band, the video for “Summer Girl” has essentially the same feel as Licorice Pizza.

But without the 70s—for as dark of a time as it was—to lend a rose-colored flourish to the environment, Licorice Pizza would not be as idyllic as it is. Anderson, too, remarked, “I think it’s a very accurate representation of that very romantic time. You could just go! Go ride your bike, go to the movies, go do something, get out of the house, go away!” Now, “going to do something,” “getting out of the house” and “going away” are decidedly more dangerous activities, if not altogether herculean. Which is why setting a romance (whether May-December or not) in the present era has far less appeal to any screenwriter. Or audience, for that matter.