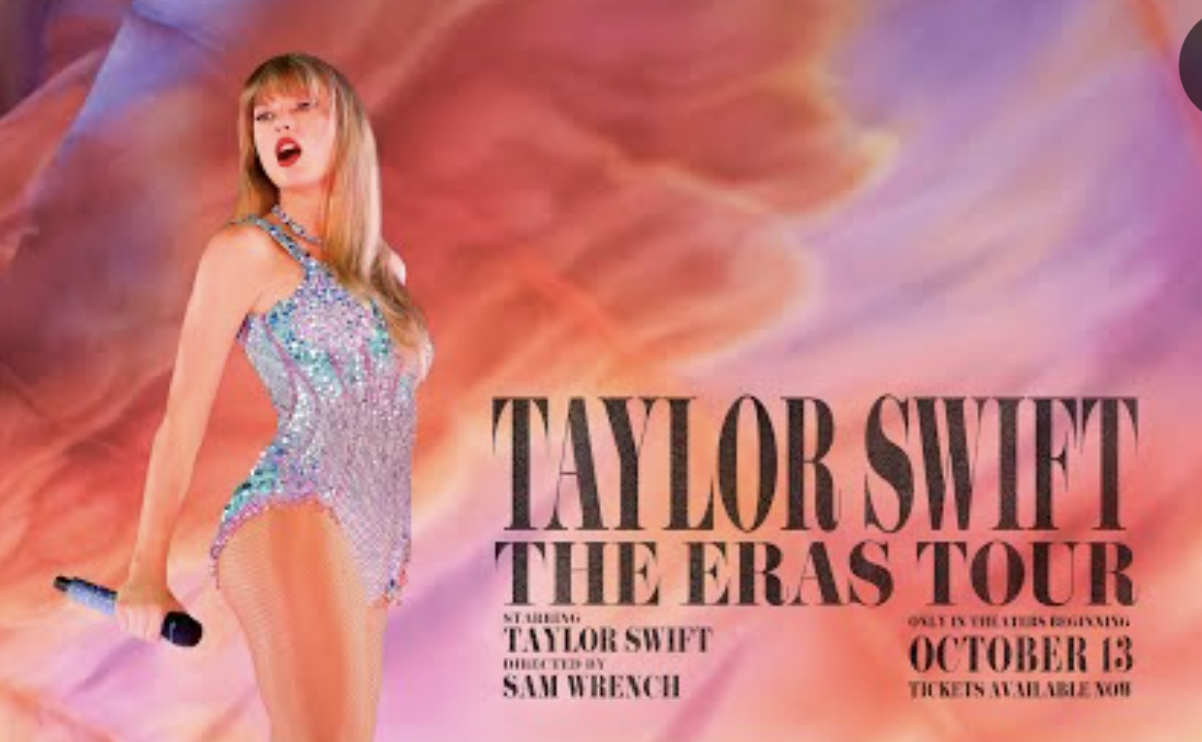

Having already shattered Marvel movie records by raking in twenty-six million dollars in presale tickets alone, it’s evident that audience members are experiencing the same lack of a moral dilemma as Taylor Swift when it comes to the Eras Tour film. On Swift’s side of things, she wants to add to her already burgeoning bank account under the pretense of “giving the fans what they want.” And on the fans’ side of things, many want to see the concert that they likely couldn’t get tickets to. Whether for financial reasons or Ticketmaster fuckery/simply not being able to beat everyone else to the punch before tickets sold out. So sure, theoretically, everyone “wins,” right? Save for the SAG-AFTRA and WGA members (the DGA remains conveniently off to the sidelines in this matter) who have been on strike since mid-summer.

For those wondering how Swift was able to sidestep the limitations set forth by the strike, it’s because 1) she falls under the category of being an “independent production” and 2) she secured an interim agreement with SAG-AFTRA by agreeing to all the demands they’ve made of the studios. This includes giving the union members higher pay, better residuals for streaming and increased breaks during production. Some would ask, “What’s so wrong with that? It actually makes her sound like a saint.” Plus, it plays to the union’s belief that by increasing independent competition against the studios via these interim agreements, it will take enough money out of their bag for people like Disney’s Bob Iger (the biggest villain to the actors and writers in this ever-escalating melodrama), Warner Bros. Discovery’s David Zaslav and Amazon’s Jennifer Salke to quake in their very expensive designer boots. That desired result, unfortunately, doesn’t seem all that probable.

For, not only does such a maneuver prove to studio heads like Iger that it really is just a matter of “starving them out” based on how desperate they are to step across picket lines when it suits them, but it also shows that there is no such thing as “complete solidarity” when the carrot of cold, hard cash is dangled (and Swift has plenty of it to dangle should she want to release any other project as well). Because while some might be able to secure the financial benefit of an interim agreement, many others have not and will not be able to as the strike continues. This, in turn, has the potential for increasing the chance of infighting and petty squabbles over who is truly committed to outlasting the studios as the strike wears on, despite SAG-AFTRA’s encouragement of entering into interim agreements. For, in their estimation, the more productions that can go forward without studio participation, the more that “competitive pressure” will be placed on studios to “yield” to the unions.

This skewed perception is perhaps a symptom of being directly responsible for creating “Hollywood endings” for a living. In real life, however, it’s never going to happen. The studios know their chance for greater profits off the potential that AI can give them (a scenario best elucidated by the first episode of Black Mirror’s sixth season, “Joan Is Awful”) is too “once-in-a-lifetime” to ignore. For anytime a “new frontier” is unearthed, that’s when people who get in on the ground floor are able to obtain what will later be called generational wealth. It happened with the railroad, it happened with the Gold Rush, it happened with the internet and it’s sure to happen with AI. The common denominator in every new enterprise being to hoard the resources. A task that the studio system has long been adept at despite its many peaks and valleys over the decades.

This includes the joint union strike that also occurred sixty-three years ago (with current strikers naturally looking to it as a precedent for guidance in this moment). Just as is the case now, it started with the WGA halting their work on January 16, 1960. And, just as is the case now, one of the main catalysts was a nefarious new medium that was stealing from their pockets: TV. So it was that among their top demands (apart from the studios agreeing to pay into the guild’s health and retirement plans) was increased residuals for content that was shown on television. Decades later, that now extends to rightly wanting increased residuals for content distributed through streaming. In 1960, it only took SAG (who wouldn’t join with AFTRA until 2012) about three more months to commence their own strike on March 7th. And yet, although they started later, their strike ended sooner, reaching an agreement with studios by April 18, 1960.

For the writers, however, things were not so easily resolved, with their strike lasting until June 12th. This time around, it might not be so easy for actors to reach an agreement, considering all of their likenesses being profited from ad infinitum is on the line. That’s no matter to Swift, though, as she has already suffered through her issues with ownership over what’s hers. In that regard, it seems odd that she doesn’t have more empathy for the delicacy of this strike, believing instead that she’s swooping in like some kind of savior to offer work to a select few people in the industry. And yes, that’s how many others see the act of releasing the Eras Tour at a time like this as well, heralding her as the “disruptor” of the year (of course, Glass Onion was sure to clarify that so-called disruptors [usually millionaires and billionaires with the means to disrupt] are the most conformist of all). Even though what she really disrupted was the work of many other bona fide actors who had projects slated to come out on or around the same day (October 13th).

This extended not only to Jason Blum’s The Exorcist: The Believer, but also to Meg Ryan’s What Happens Later and Martin Scorsese’s Killers of the Flower Moon, the latter of which will undoubtedly face competition with Swift for space on IMAX screens. It’s not difficult to guess which “auteur” will win out. For one should never underestimate the power of the Swifties. Alas, it’s a shame their power has to affect someone as genuinely passionate about the moviegoing experience as Scorsese.

Considering the political clout Swift has in just about all matters (so much that politicians actually ask her to do things in order to effect change), it’s a missed opportunity for her to tiptoe around the limitations of the strike rather than honor them fully. Do something to actually help SAG-AFTRA and WGA win “the great war” against the studios by showing a true sign of her uncompromised solidarity. Releasing a movie during a peak stalemate in negotiations hardly does that. It instead desensitizes audiences to the importance of the strikes and comes across as an indication to studios that people are growing so impatient about wanting to “release their shit”—while audiences remain equally as hungry to swallow said shit—that all the CEOs have to do is keep waiting a little longer to “starve them out until they have to sell their apartments.” At which point, the desperation will take hold strongly enough to make the guilds more amenable to concessions. For this is hardly the “pleasant” strike of 1960, or even 1981, 1988 and 2007-08. That much was made clear when the writers were practically out for blood upon learning that Drew Barrymore would restart production of The Drew Barrymore Show without writers. Unlike Swift, however, her decision was not met with praise or being called a “disruptor,” even though she, too, did not violate any strike rules in doing so.

The backlash against Barrymore’s choice to go forward with her show was so strong, in fact, that she was quickly dropped as the host of the National Book Awards. After all, its “dedicat[ion] to celebrating the power of literature, and the incomparable contributions of writers to our culture” certainly doesn’t seem to align with Barrymore’s views at this time. Of course, if Taylor Swift had done something similar, many would have likely been quicker to find a way to justify her actions and/or accept her inevitable apology. Such is the primary perk of being America’s sweetheart. And the primary bane of being a lowly guild member. Because, obviously, after the “bang” of Swift’s film in theaters this fall, there’s going to be a big bust afterward. Which will only corroborate the major studios’ conviction that Swift is an anomaly in the landscape of interim agreements. That’s when it will become painfully clear to the guilds that winter is very much coming. Not for Swift though…