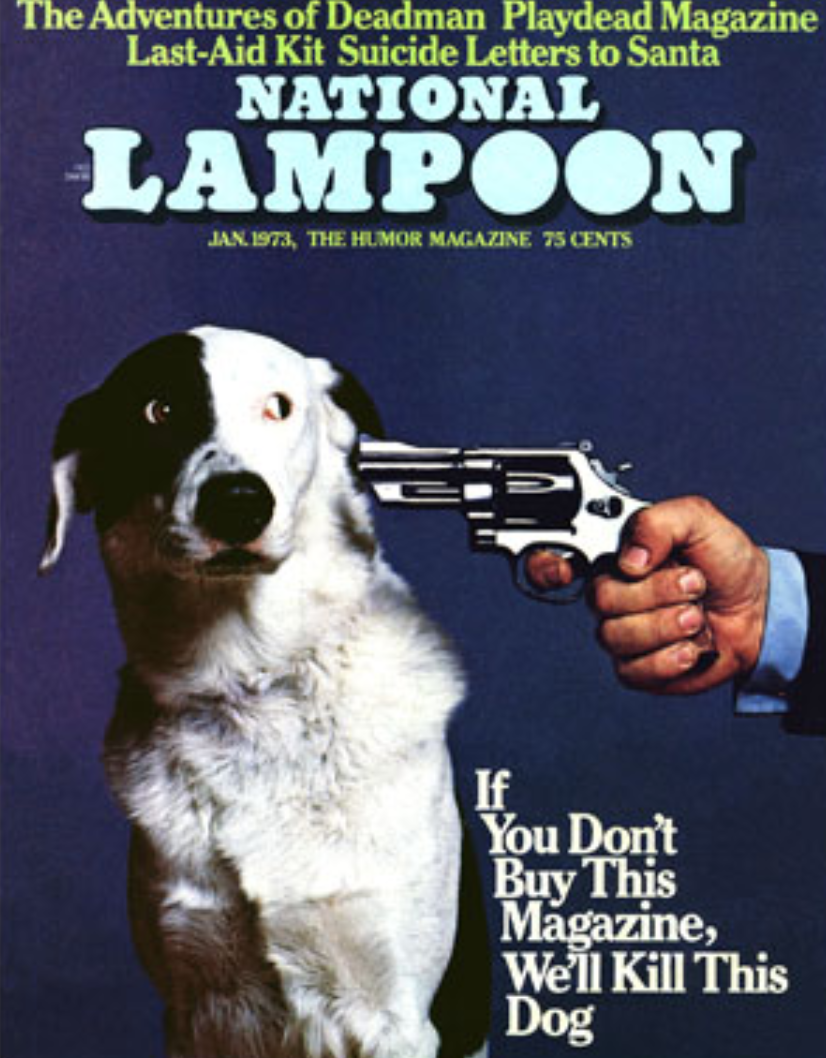

Of all the people who you wouldn’t expect to have a biopic made about them, Doug Kenney is among the men who top the list. Not so much because he wasn’t important and influential, but because few people are aware of this man’s behind-the-scenes presence in shaping modern comedy. And yet, everything about Kenney’s short, jam-packed with excitement life was unexpected. From ending up at Harvard to licensing the Harvard Lampoon to create his own National Lampoon magazine instead of pursuing the type of “serious” career that Harvard is intended to serve as a launching pad toward, nothing about Kenney followed a “normal” path. And he didn’t want it to for his friend and business partner, Henry Beard (Domnhall Gleeson), either.

Told in the irreverent style that Kenney would have approved of by director David Wain (of Wet Hot American Summer fame) and co-screenwriters John Aboud and Michael Colton (both former editors themselves of the Harvard Lampoon), A Futile and Stupid Gesture is the disjointed biopic you didn’t know you wanted to see. Starting from the breaking the fourth wall beginning, we instantly know this isn’t going to be a by the book homage to Kenney’s legacy. Also there to set the tone from the outset is one of the scrawlings found in Kenney’s Kauai hotel room that would become his great aphorism: “These last few days are among the happiest I’ve ever ignored.” And, to this point, Kenney ignored a great many things about himself of a positive bent that he chose to discount in favor of seeing all that was wrong in his life and with the nature of his success. Naturally, this self-doubt, as the film very clearly posits, was a direct result of his father’s lack of approval of the unconventional manner by which he made his fortune. Harry (Harry Groener), a patriarch who seemed to clearly favor the golden son who died in his twenties of kidney disease when Doug was twelve, doesn’t once show any sign of pride in Doug’s work throughout the film (well, at least not until he’s dead).

Raised in Chagrin Falls, Ohio (an ironically named location that Doug uses as an introduction to most of the women he meets), Doug’s traditionally-oriented parents could never seem to wrap their heads around labeling Doug a success. This, surely, couldn’t have helped in matters pertaining to inspiring Doug to “rein it in,” drug-wise. Knowing that he would never be impressive in the way he needed to be in order to achieve “the right kind” of parental approval, Doug had no reason not to go full-tilt in his penchant for cocaine use. But that was later, after the innocent tomfoolery of his days at Harvard with Henry, where the food fight concept viewers would see in Animal House began. That A Futile and Stupid Gesture can vacillate erratically between tragedy and comedy (like Doug himself), blending the two so seamlessly, speaks to the fine line Kenney’s life itself toed between these genres–and, of course, that both categories can’t exist without one another.

Largely because of the intense pressure Kenney felt while helping to run the magazine, paired with seemingly uncontrollable drug use, his role went from being in Editor-in-Chief to senior editor to mere editor by the end of the 1970s, when he had already made his millions and started transitioning into screenwriting anyway. This was also after expanding the scope of National Lampoon to radio, and, with it, comedy albums. The pressure to create quality content at the same level with all of this expectation on quantity began to wear on Doug’s judgment, specifically with drug intake. At one point during the film, a concerned Chevy Chase (Joel McHale) tries to express “earnestness” about Doug’s shambled love life with his wife, Alex Garcia-Mata (Camille Guaty), amid his clear inability to focus on anything other than matters pertaining to creativity and career. As the aged version of Doug (Martin Mull)–who will never come to fruition in real life–narrates, “The more ads you sell, the more pages you have to print. Someone has to write those pages. Then there’s the other pieces to edit, art to commission, headlines, captions and cartoons to fix, all on a deadline. On top of that you expand into books, albums, then, oh the radio show, based on your successful magazine is also successful, and holy shit an hour is a lot of time to fill.” The wear and tear on his body and mind was, in short, starting to manifest to friends and co-workers.

But Doug, ever of the “keep things light” philosophy, cuts Chase off at the pass of comfort by stating simply, “Look, I know I’m fucked up. I’m fucked up, all right? But there’s just too much work to be done.” Work that required a dangerous cocktail of uppers and downers that included weed, LSD and, of course, coke-ah-een. He was the good time guy that everyone wanted to be around until it all started to get muddled in grimness, the peak of which is showcased at a press conference for Caddyshack as he drunkenly condemned his own film to all present (even his parents)–spurred on by a recent screening of Airplane! he saw and subsequently made him feel insecure about the trajectory of his own comedic sensibilities. Later in life, Caddyshack would be vindicated as a cult classic, if not yet another indication of Kenney’s insulated world of dweebish white male humor (a phenomenon addressed when “old Doug” tells now dead Doug at his funeral, “Look at this, you were beloved by so many white people.” Because, you know, it’s 2018, and you have to ream and apologize for whites where you can).

But before Hollywood came knocking–or rather, before Kenney went to knock on its door–Beard helped him to channel the theme of an unsuitable for consumption novel he wrote while taking one of his many breaks into “the meaningless cruelty of being young in America: the high school yearbook.” This would become the illustrious National Lampoon’s 1964 High School Yearbook. Deviating very minimally–as most great parodies must not–from their source material, basing the content on P.J. O’Rourke’s own Devilbiss High School yearbook, where he attended for a few years in the early 60s, made the yearbook yet another tick in the column of “comedy genius” for Doug. The point being, as elucidated by A Futile and Stupid Gesture, is that having the Midas touch for so long on everything in his career–yet not where he wanted to have it: his personal life–meant that the failure of Caddyshack was a heavy wallop to take. Hence, differing perspectives on whether or not Kenney’s death was truly accidental (whatever the case, he fell off a cliff at thirty-three–keeping it unconventional until the end).

And maybe all of the incentives behind what Doug did were merely reflections of a futile and stupid gesture. Yet, one could say that about life itself. And without gestures that are occasionally crude, offensive and shocking, then perhaps it really would all be futile and stupid. That being said, perhaps we should all declare, “Food fight!” when things start getting too serious in this world that so often takes itself too seriously, ultimately still somehow allowing the election of goons. God or whoever knows that it’s better than getting upset about the shitstorm flinging happening in the White House right now, which Kenney would undoubtedly have been a shrewd commentator on. And even if A Futile and Stupid Gesture might appeal only to a niche audience of comedy-obsessed nerds seeking to understand the origins of new generations like Apatow and company, it nonetheless sheds light on a troubled man who proved the tears of a clown can often be very profitable in between the self-destruction.