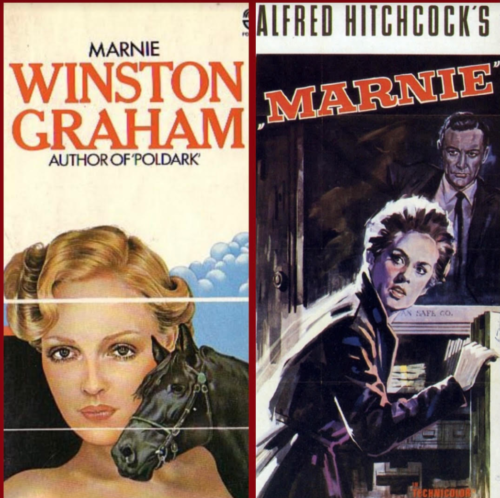

Marnie might be one of the most problematic Alfred Hitchcock movies of all-time, which is really saying something as there are so many affronting cinematic masterpieces in his canon. But, like most Hitchcock fare, this story was not spawned, precisely, from his own mind, but that of an author’s. In this case, Winston Graham’s 1961 novel of the same name. Willing, as most books are to, go deeper and darker than the movie adaptation, Hitchcock and his screenwriter, Jay Presson Allen, made some rather surprising changes to the film version.

For starters, it seemed particularly unlikely that Hitchcock, of all people, would opt to amend the setting from England to the U.S. After all, it was practically as though Graham had handed him the opportunity to “keep it local.” But by this time in Hitchcock’s career, he had turned decidedly “Hollywood,” favoring his productions to take place in the U.S. rather than his native land. Thus, the setting was altered to Philadelphia (by way of Pittsburgh), instead of Marnie’s original primary location of London (by way of Manchester). In fact, after the 1950s, Hitchcock only returned to London as his primary setting with his grisly penultimate film, Frenzy (released in 1972).

Tippi Hedren—cast in the lead role of Margaret “Marnie” Edgar (Elmer in the book)—might have had something to do with “Hitch” being so eager to Americanize the context (regardless of “settling” for her instead of the then recently-made-royal Grace Kelly). For it was no secret that he had developed something of an unnatural obsession with her. Usurped perhaps only by the one Mark Rutland (a freshly-James Bond’ed Sean Connery) has with Marnie. The casting of Mark as someone so debonair—as opposed to the meeker man presented in the book—immediately adds to the Hitchcockian ideal of a man “conquering” or “taming” a “wild” woman. Wild, meaning, of course, that she’s not interested in men, least of all marrying one. As Movie Marnie phrases it after Mark suggests she see a psychiatrist, “Men! You say ‘no thanks’ to one of them and, bingo, you’re a candidate for the funny farm. It would be hilarious if it weren’t pathetic.”

These occasional “outbursts” from Movie Marnie pale in comparison to getting the interior picture of her mind as she tells the story from her first-person perspective in the novel. Taking that away by not including at least some voiceover was perhaps the first mistake Presson Allen’s adaptation made in transforming Marnie further into the trope of “just a girl who needed to be broken in by the right man.” Rutland, naturally, fancies himself that man. But so does another character in the book that gets excised: Terry Holbrook. As a co-owner with a vested stake in Rutland’s, he is quick to exert his “authority” over Marnie when she first takes the position.

Marnie’s contempt for men and people in general are made so much clearer when described from her viewpoint. Indeed, from the very start of the book, she informs us, “People might think it lonely living on my own nearly all the time, but I never found it lonely. I always had plenty to think about, and anyway maybe I’m not so good on people.” Least of all men, as made clear when her “cleansing” process (a.k.a. soaking in the tub after a heist from her now defunct job under a now defunct alias) is interrupted by an overzealous suitor named Ronnie Oliver (also jettisoned as a minor character in Hitchcock’s version). Phoning her to nag about when they might see each other again. This is when Marnie internally muses, “Human beings…well, they just won’t be ticked off, docketed, that’s what’s wrong with them; they spill over and spoil your plans…” Sort of the way Hitchcock spoiled Hedren’s plans for a more robust career until she refused his sexual advances. In any case, Marnie’s plans always consist of moving on to the next job.

With other geographical tweaks from the book, Marnie’s mom, Bernice (Louise Latham), lives not in Torquay, but Baltimore. With Hitchcock having swapped out one working-class, seaside town for another. Kendalls, the place where she gets her only work reference in order to secure a job at Rutland & Co. is in London, while the latter company is based in the North London suburb of Barnet. She’s now transcended into a new fungible identity for her next office job: Mary Taylor (after her stints as Marion Holland and Mollie Jeffrey). This after waiting a year in the wake of robbing the Gaumont Cinema where she worked (movie theaters, after all, used to make a lot more money). Another detail snipped out in favor of keeping Marnie’s character an exclusive “fan” of the office setting for her heists.

Another seemingly arbitrary alteration in the film is making Rutland a client of Sidney Strutt’s (Martin Gabel), thus he knows right away that “Mary Taylor” looks an awful lot like the girl who just stole about ten thousand dollars from her now ex-employer. In fact, Mark walks in to see Strutt as he’s being interviewed by the police. Recognizing her in some vague way when she turns up at Rutland’s, Mark instructs Ward (S. John Launer), the manager, to hire her with a small nod. More reluctant to do so in the movie than in the book, he obliges. Being that Mark is the silver-spooned son of the owner in charge, he certainly has the clout to get whoever he wants hired. In Hitchcock’s Marnie, Mark’s affluent father (Alan Napier) is the parent who’s still alive, but in the book, it is his mother. This, too, lends him more “sympathy” and “gentleness” as a character, whereas being challenged by the looming so-called masculinity of his patriarch is partially what makes him so much more “rough-hewn” on film.

Before mild-mannered Book Mark can start moving in on Marnie, Terry beats him to the chase with his more overt lechery. Obviously, Mark’s sister-in-law, Lil Mainwaring (Diane Baker), is meant to replace the void where Holbrook is in the movie, what with all her meddling and insinuating. But the effect is lost, for there’s a layer to Marnie’s character missing without Holbrook—one that shows she feels her darkness is “worthier” of someone as vile as Holbrook. Hence, her frequenting the poker games at his house even after she’s forced into marrying Mark.

Which brings us to the part where Marnie is caught after going through with stealing from Rutland’s. In the book, the affront is even greater to Mark because Marnie spent quite a great deal longer at the firm than she usually would at another office—allowing herself to become too known, too “read.” Even went to a company dance that her former, more cautious self never would have agreed to (Marnie’s literary narration confirms, “She really had been a bit of a fool, Mary Taylor, getting so involved”). In the film, as in the book, Marnie also goes to the horse races with Mark, but Book Marnie reveals far too much about her class insecurity when she defends a group of ruffian Teddy boys to him, explaining of the chip on their shoulder (because she knows it all too well): “Most are just—restless. You don’t understand. They’ve nearly all got jobs that bring them in good money, but they’re caught on a sort of treadmill and they’ll not earn much more over the next forty years. They’ve brains enough to know that. You try it out and see if it wouldn’t make you restless.”

Marnie, too, is restless—ready to shake this Mary Taylor guise and live off the fat of her stolen bounty. She’s also eager to see her horse, Forio…essentially the only creature she can stand (because her mother is clearly too cold to love, having passed that trait down to Marnie). Little does she know, it’s going to that stable that will lead Mark right to her, for her he remembers a specific detail she told him that sends him that way in search of her. Movie Mark is quick to tell her (at a Howard Johnson’s—sign o’ the times) how his sleuthing led him to her, while Book Mark keeps it under wraps for much longer, preferring to enjoy such things as their honeymoon after cornering her into marriage before giving up the secret to his success in finding her.

In Hitchcock’s version, Lil’s prying nature makes her realize early on that there’s something off about the entire affair, especially Marnie herself. Eavesdropping, she overhears Marnie talking to her mother on the phone, later relaying the information to Mark, who, in the book never learns of Marnie having an alive mother. But such are the ways in which Hitchcock remakes Movie Mark into a more “take-charge” presence. Minus the part where Book Mark actually makes Marnie see a psychiatrist in exchange for bringing Forio to their property. Movie Mark is far more spoiling of his new wife, simply bringing Forio to the Estate as yet another way to get into Marnie’s good graces. Which seems rather impossible in both iterations of the story.

As for Marnie’s rape on their honeymoon, it is treated with far less shruggingness in the book, where, at the very least, Mark tries to have a conversation about it the following morning, dumbly remarking, “That can’t have been very pleasant for you. I’m sorry. Nor was it for me. No man ever really wants it that way, however much he may imagine he does.” The suicide attempt that Marnie naturally tries to make after her violation is also handled with more “winking humor” than in the book, with Movie Marnie trying to drown herself on the boat’s pool rather than swimming far out in the water at the beach to do it, whereupon Mark rushes to rescue her. In the film, Mark plucks her from the pool, rolls her over and waits for her to say, “I wanted to kill myself, not feed the fish” when he asks why she didn’t just jump overboard.

Perhaps most noticeably divergent (in plot as opposed to style) of all is one of the final denouements during which Marnie is engaged in a fox hunt, riding Forio for the occasion. Breaking away from the others, Marnie sends Forio galloping away with Mark in pursuit. Mark who keeps calling out, “Marnie!” only for her to keep running, knowing no other response in her life than flight. As the two make a final jump over the fence, Mark’s horse throws him off in a perilous way, with Marnie, too, being thrown—except it’s Forio that’s the wounded party in their permutation. Seeing Mark barely conscious, Marnie calls for help from a nearby farmhand, and soon, Mark ends up in the hospital. In the film, it is Lil who chases after Marnie, with Mark never getting harmed in any way, therefore the high stakes involving his potential forgiveness (yet again) are somewhat lowered. In both scenarios, unfortunately, Marnie is left with no choice but to kill her beloved Forio (in the movie, she does it herself, in the book, she watches someone else do it).

Stylistically speaking, Hitchcock (like Kubrick after him) was committed to bringing his own auteur flair to the project. Thus, we have the somewhat overly cheesy (in the present context) appearance of an all-red screen anytime Marnie sees the color red. For it is meant to remind her of the repressed memory of her killing the sailor her mother was prostituting herself for after things between them got violent one evening when Marnie was just a small child. But what the movie isn’t willing to incorporate, “darkness”-wise, is how Marnie discovers the truth about her mother (after her death, therefore detracting from the “catharsis” presented in the movie) in a newspaper clipping she kept tucked away in a box. In it, it is described how she killed her own newborn child in a moment of “temporary insanity.” After the funeral, her Uncle Stephen (nonexistent in the film) tries to better explain to Marnie her mother’s psychosis—a direct result of their oppressive, overly religious father. An upbringing that inevitably led Marnie’s mother down the path of being promiscuous and engaging in the full potential of that while her husband was away in the war (this, in turn, leading Marnie’s mother to raise her to be the exact opposite of who she was, conditioning her to eschew men at all costs).

As Stephen says, Marnie’s mother was always capable of “self-deception” (much like Marnie herself). And so, when she became pregnant by another man, her ability to deceive herself about her “nocturnal life” was blow to pieces. That is, unless there was never evidence of this product of sin. Ergo, killing her own child quickly after he was born. And this, to be sure, is one aspect of “psychology” Hitchcock didn’t want to bring into his film, still meant to be awash in the glitz and glamor of Hollywood. Which is why its ending is so neatly wrapped up with Mark able to play the knight in shining armor rather than still being holed up in the hospital while Marnie is left to face the consequences of her past indiscretions on her own (courtesy of Terry Holbrook’s treachery).

And so, even the most “macabre” directors and screenwriters often have difficulty of keeping a book’s “grimness” (a.k.a. reality) intact. For we must always, always tell the more faint-of-heart watchers (rather than readers) what they want to hear. Some small consolation about how, no matter how fucked up a person is, there’s always a chance for redemption. In the novel version of Marnie, that idea is left far more in question (you know, like in The Bell Jar as well).