If Air seeks to emphasize one thing, it’s that you should always leverage your talent to secure the utmost profit. That’s certainly what Michael Jordan did back in 1984 as a rookie who made an unthinkable negotiation with Nike. One that would, for the first time in history, allow an athlete like Jordan to earn a percentage of every pair of Air Jordans sold. After all, it was his name on the sneakers, his name spurring all the sales. So why shouldn’t he get his cut? This question is present throughout the narrative thread of Air, which revolves entirely around the lead-up to making this landmark deal. Marking Ben Affleck’s fifth directorial effort following Gone Baby Gone, The Town, Argo and Live By Night, Air is a much more blatant nod to the “American dream.” You know, the one that pertains solely to bowing down to capitalism a.k.a. “getting this money.” Ironically, it’s also distributed by Amazon, which Nike no longer sells their shoes through in a bid to “elevate consumer experiences through more direct, personal relationships.”

Sort of the way Jordan wanted to elevate the consumer experience of his adoring fans by giving them “a piece of himself” through a shoe. Fittingly enough, both Nike and Michael Jordan are quintessential American dream stories, with the latter being a shoestring operation (pun intended) co-founded in 1964 by University of Oregon track athlete Phil Knight (Affleck) and his coach, Bill Bowerman (though Alex Convery, the writer of Air, doesn’t bother to mention his name). It was Knight who sold the company’s (then known as Blue Ribbon Sports) first shoe offerings (made by Onitsuka Tiger, a brand that, for whatever reason, agreed to let Knight be the U.S.’ exclusive distributor) out of the back of his car at track meets most of the time. Steadily, Blue Ribbon Sports kept making a name for itself as a leader in distributing Japanese running shoes. But it was in 1971 that Bowerman fucked around with his own innovation by using his wife’s waffle iron to create a different kind of rubber sole for the benefit of runners. One that was lightweight, therefore conducive to increasing speed. This was also the year the company rebranded to Nike and was bequeathed with its signature swoosh logo by graphic designer Carolyn Davidson. With the “Moon Shoe” and the “Waffle Trainer” released in 1972 and 1974 respectively, Nike sales exploded into a multimillion-dollar enterprise.

Jordan’s Cinderella story comes across as having slightly fewer hiccups in his rise to prominence, the main one being his slight by the varsity high school team when he was a sophomore at Emsley A. Laney High School in Wilmington, North Carolina. Written off as too short for varsity, Jordan waited patiently to grow four more inches and asserted himself as the star of Laney’s JV team. After getting his spot on varsity, it didn’t take long for a number of colleges to offer him a scholarship. He settled on University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, quickly distinguishing himself on the basketball team there and having no trouble eventually catching the eye of Sonny Vaccaro (Matt Damon, rejoining his true love onscreen), Nike’s then basketball talent scout (at a time when such “lax” job roles were still in existence). Convinced of Jordan’s status as a once-in-a-generation talent, he begs and pleads with Knight to use the entire basketball budget to offer Jordan an endorsement deal.

Alas, although named after the Greek goddess who personifies victory, Nike was anything but victorious in being a basketball shoe contender with the likes of Converse and Adidas as 1984 commenced. After all, the company had been built on running shoes. That had always been their bread and butter. Nonetheless, Vaccaro still can’t figure out why basketball players are so averse to putting their faith in Nike. But, as Howard White (Chris Tucker), the VP of Nike’s Basketball Athlete Relations tells Sonny, “Nike is a damn jogging company. Black people don’t jog. You ain’t gonna catch no Black person running twenty-six miles for no damn reason. Man, the cops probably pull you over thinkin’ you done stole something.” Which isn’t far off considering the need for shirts like, “Don’t Shoot, It’s Just Cardio” (tragically inspired by the death of Ahmaud Arbery).

Rob Strasser (Jason Bateman), the VP of Marketing for Basketball, is more naively optimistic during a meeting in which he says, “Mr. Orwell was right. 1984 has been a tough year. Our sales are down, our growth is down. But this company is about who we really are when we are down for the count.” That said, Strasser and Knight both insist they have a strict 250K budget to attract three players. Sonny tells Strasser he doesn’t want to sign three players, he wants to sign just one: Jordan. He paints Strasser the innovative-for-its-time picture, “We build a shoe line just around him. We tap into something deeper, into the player’s identity.” This being something that would become the subsequent norm with endorsement deals, not just from sports players, but every kind of celebrity.

To this end, it’s of no small significance that Air opens with Dire Straits’ “Money For Nothing,” a song that derides famous ilk (namely, rock stars) who get money for doing no “real” work, like those who have to fritter their hours away in a minimum wage job at an appliance store (the site where Mark Knopfler overheard a man making derisive comments about the people he was seeing on MTV and then turned the rant into “Money For Nothing”). Jordan, too, might be seen that way by some, at least for making millions (billions?) for doing nothing other than allowing a shoe with his name and silhouette on it to be sold. And as “Money For Nothing” plays, Affleck gets us into the mindset of what the 80s were all about: consumer culture melding with pop culture. For it was in the 80s that the potential for endorsement deals, fueled by Reaganomics’ love of neoliberalism on steroids, were fully realized and taken advantage of.

Sonny, seeing something entirely American in Jordan, crystallizes his feelings about him to Phil by insisting that he is “the most competitive guy I’ve ever seen. He is a fucking killer.” And that means he’s going to kill for Nike, profit-wise. As Sonny chases down a meeting with Jordan, who has made his disdain for the company abundantly clear (especially as he “loves” Adidas), it’s through his mother, Deloris (Viola Davis, who, although Jordan had no involvement in the production of the film, was offered as a suggestion by him to play the part), that Sonny finds his “in” with Michael. Much to the consternation of Michael’s agent, David Falk (Chris Messina), who distinctly warns Sonny not to contact the family.

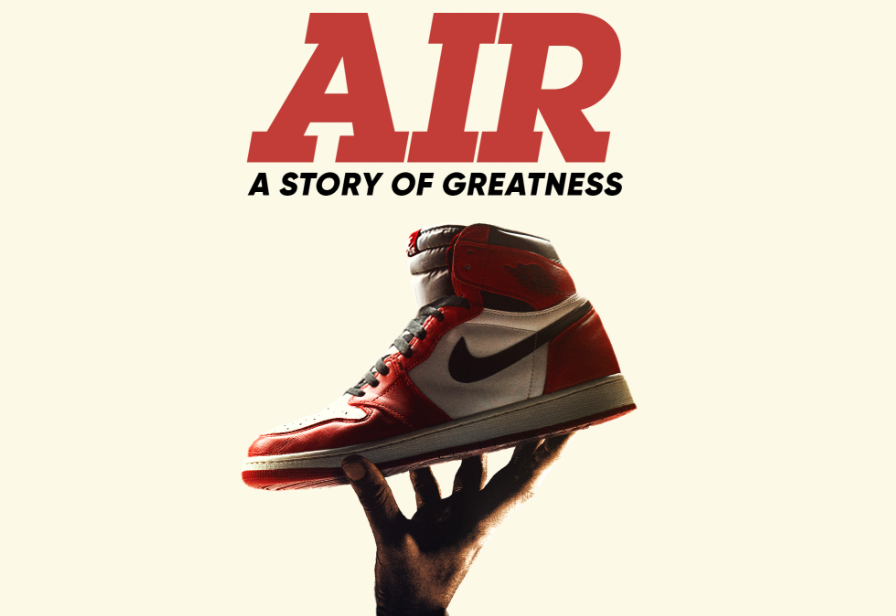

But Sonny has no interest in following rules, if that hadn’t already been made evident. And when he finally does land the pitch meeting with Jordan, he’s sure to tell him and his parents that Michael’s trajectory is “an American story, and that’s why Americans are gonna love it.” He then adds, as a coup de grâce in terms of flattery, “A shoe is just a shoe…until somebody steps into it [words Deloris will remind him of later when bargaining for Michael’s cut of the profits]. Then it has meaning. The rest of us just want a chance to touch that greatness.” And that, in the end, is how Jordan makes four hundred million dollars a year in passive income from a shoe.

Even if it was an initial struggle for Deloris to lock down that income. Indeed, when Sonny tells her that Nike will never go for her and Michael’s demand and that the business is simply unfair in that regard, Deloris replies, “I agree that the business is unfair. It’s unfair to my son, it’s unfair to people like you. But every once in a while, someone comes along that’s so extraordinary, that it forces those reluctant to part with some of [their] wealth [to do so]. Not out of charity, but out of greed, because they are so very special. And even more rare, that person demands to be treated according to their worth, because they understand what they are worth.”

With such an ardent speech about getting money, getting paid, it highlights that, more than just being a movie about how capitalism allows companies to exploit those making the most money for them, Air is about how capitalism indoctrinates the human brain so much as to make it believe that everything has to be about money. That the greatest art of all is not the art or skill itself, but how to get the most one possibly can for it. So it is that Bruce Springsteen’s always cringe-y hit, “Born in the U.S.A.,” plays while viewers are given epilogues to each person’s financially profitable fate. Funnily enough, Strasser had specifically mentioned to Vaccaro earlier in the film that one of the songs most beloved by Republicans (Reagan himself famously cited it for his presidential “cause”) is not about the hallowed notion of the American dream at all. In fact, as he tells Sonny, he was listening to it on his way to work most mornings (it had just come out during the year Air takes place), and he was all “fired up about American freedom…but this morning, I really focused on the words. And it is not about freedom. Like, not in any way. It’s about a guy who comes home from Vietnam, can’t find a job and I’m just belting it out enthusiastically.”

There’s something to that analogy in looking for the deeper, perhaps unwitting meaning to Air. It isn’t really about the beauty of the American dream, but how ugly and petty it makes everyone pursuing it for the sake of as many pieces of paper as possible.

[…] Genna Rivieccio Source link […]