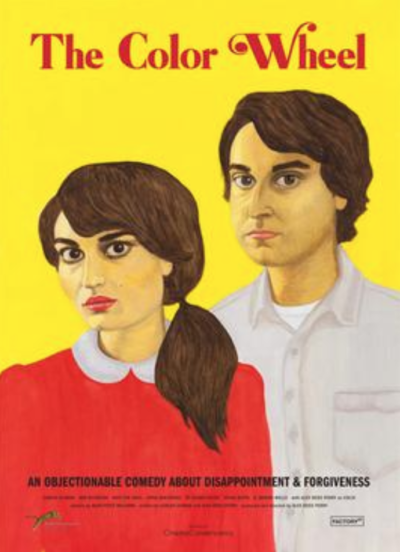

The steady presence of Alex Ross Perry in the world of what can still vaguely be constituted as “indie film” (once associated only with Miramax-distributed projects) began with 2009’s Impolex and continued, strangely, with an appearance in the behemoth of a self-pitying narrative that would launch Lena Dunham’s career, Tiny Furniture. But it was with 2011’s short (by feature film standards), dialogue-laden The Color Wheel, about the, shall we say, “fraught” relationship between brother and sister Colin (Perry) and J.R. (Carlen Altman), that asserted his indie god status. Intimating with ease each party’s station in life, we can immediately apprehend that J.R. is still semi college-aged and has apparently been estranged from Colin for some time now until the desperation of needing him to help her move out her things from her (ex) boyfriend/professor’s house prompts her to reach out.

As Colin tells it to his girlfriend of three and a half years, Zoe (Ry Russo-Young), “She asked for a favor. You don’t have any siblings, so you have no frame of reference for what it’s like when one of them asks for a favor.” And though this explanation seems straightforward enough, the dynamic between Colin and J.R. has already been established, somewhat unbeknownst to the viewer, at the outset of the film, at which time J.R. wakes up next to Colin with her headband over her eyes like a blindfold. Drinking coffee outside, Colin later joins her, whereupon she mocks him “in a sisterly fashion,” ” Nice shirt.”

The underlying tension between the two persists as we go back to the start of her arrival at Colin’s abode, with intercut moments of them driving together (Star of David waving wildly from the rearview mirror), where her terse conversation with Zoe commences. Zoe, condescending to her attempts at becoming an actress/news anchor, balks, “Well don’t you look like a movie star.” J.R., ignoring her ire, returns, “Thanks, so do you,” later adding, “The movie star I meant was the bathtub monster in The Shining.” The underpinning jealousy J.R. has for Zoe manages to remain mildly under control as she departs rather quickly with Colin, setting off on the drive to Professor Neil Chadwick’s (Bob Byington)–a name to match the level of pompousness at play–with but one stop along the way: a place called Motel Funcenter.

As a Christian-operated establishment, it’s apparently a prerequisite to prove one’s marriage (and therefore eligibility to share a bed) by kissing in front of the clerk, for as he states, “We don’t allow co-eds to co-habitate unless they’re married.” Somewhat unconvincingly, J.R. comments, “Uh, that shouldn’t be a problem, we’re brother and sister. No funny business here.” The clerk then states, “Brother and sister? That’s foul. In a way that’s even worse than if you were a couple sinful kids up to no good.” So it is that they backpedal, claiming to be married and then kissing as a means of palpable assurance. It’s already much further than Richie Tenenbaum ever got. And much further than Wes Anderson would ever dare to go with that whole incest subplot in 2001’s The Royal Tenenbaums (even though, as we were all hit on the head with, Margot was adopted).

And though Colin knows precisely why J.R. is turning to him in her time of need, he still fishes for some sort of excuse, to which she lamely offers, “I asked you because I trust you with my stuff, and mainly because your have nobody important to tell.” The biting banter between them only escalates after J.R. finally endures the humiliation of collecting her few possessions from Neil’s (who has already moved on to another “aspiring news broadcaster”), particularly at a diner where J.R. accuses Colin of giving up on his dream for “the worst kind of existence”: doing something he’s just okay with instead of writing.

The allusions to their bubbling to the surface romantic emotions for one another only seem to bombard the viewer like an ad on YouTube before watching a music video when everything has finally come together at the end, building up to a crescendo after a particularly descriptive imagining on J.R.’s part of how Colin’s life as a professor would be. That the dastardly duo has been driven to their grandparents’ cabin in the woods after a particularly harrowing journey into the lion’s den of a party thrown by a former high school popular girl underscores the notion that they are the only two people who can understand and accept one another–even if that acceptance is muddled by much back and forth opprobrium.

That a film called The Color Wheel is shot entirely in black and white only adds to the jarring, Ingmar Bergman-like qualities of this highly intense, grit-laden narrative. One that, essentially, expounds upon the taboo theme that Anderson could never (though perhaps should reconsider trying) fully explore. Hence, The Color Wheel‘s far more niche audience.

Plus, when it comes to brother-sister incest tales, anything that we can add to the annals to help mar the filmic dominance of Flowers in the Attic is much appreciated.