As Seth Rogen tries his hand at what Lindsay Lohan pulled as Hallie Parker and Annie James in The Parent Trap already, we’re given a message throughout An American Pickle that wasn’t necessarily intentional: generational “success” is always measured in money–particularly if one’s family settled in New York. That is, after all, the entire reason Herschel Greenbaum (Rogen) took the risk on leaving his shtetl with his new wife, Sarah (Sarah Snook)–who, as Herschel points out to viewers, has both her top and bottom sets of teeth intact. Well, that and wanting to avoid the continuous raids and murders of the Cossacks. Thus, like so many other Eastern Ashkenazis evading persecution during the exodus of Russian Jews fleeing pogroms, Herschel sets out for New York. Because clubbing rats in a pickle factory has to be slightly better than digging ditches. Plus, compared to Cossacks, Americans are relatively nice (says Herschel as he’s labeled a JEW upon arriving to Ellis Island).

Like most immigrants who were enamored with the concept of “liberty” in a land still so uncharted, therefore still so moldable into what the vox populi might want (before eventually digressing into the very thing that people escaped from their original lands to avoid), Herschel and Sarah were contented with their still rather bleak existence in the “big city” (Brooklyn not being at all considered as such during the time of Herscel’s arrival in 1919). As Herschel keeps working in the factory, he finds the time to get Sarah pregnant, assured in his belief that his familial legacy will be great and that “a hundred years from now” the Greenbaum name will be associated with power and prominence. Oh how many must have thought that when they first gambled on a plague-ridden boat ride to New York Shitty. Thus, Herschel persists in his menial job, feeling assured somewhere deep down that his sacrifice now will benefit the trajectory of his lineage later. Alas, he never does get to meet his son, falling into a vat at the factory and being closed into it with the pickles as the business is declared condemned (it’s one of those overly played up surreal moments that we can only go along with in adhering to the expected suspension of disbelief required for this universe–one in which corona doesn’t exist either, though, where diseases are concerned, Herschel is very excited when he hears Jonas Salk, a fellow Jew, cured polio with his vaccine).

When Herschel is unearthed by two kids just trying to find their drone (a device used to accent the passage of time) inside the abandoned factory, the media is surprisingly nonchalant, accepting the supposedly “super scientific” explanation for how pickling preserved him for the past century. Saddened to learn that his wife and son are now dead, the doctor caring for Herschel tries to placate him by presenting his great great grandson, Ben (also Rogen), to him. Ben offers to take Herschel in, showing him the progress of the modern world, which consists primarily of comforts Herschel might never have previously imagined, including an at-home seltzer water maker a.k.a. SodaStream. Indeed, one of the most unintentionally depressing elements of the movie is that, after years of strife and unimaginable struggle for immigrant ascendants, all that exertion was ultimately so someone like Ben could sit in front of his computer living in constant fear of the most trivial matters–like the color of his logo for an app he’s working on called BoopBop.

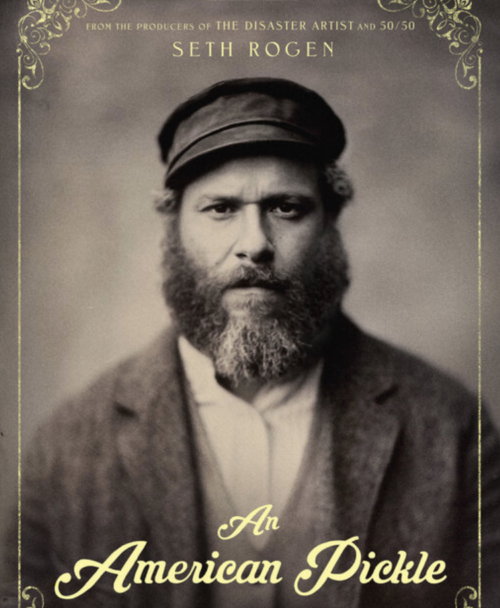

When Herschel asks him why the “silly” name, Ben shrugs that it’s the trend (Hulu, Hipmunk, etc.). Herschel cannot fathom how this is the project that Ben has chosen to invest his time and energy in. That this nebbish, meek little boy is all he has left of his legacy. This was not the “success” and “power” he had envisioned for his family line when he journeyed to Brooklyn all those years ago. Oddly, however, Herschel’s “old-timey” aesthetic (pageboy hat included) is right at home in the Williamsburg nexus–even though this trope is not really relevant anymore when taking into account that “the ‘burg” has been overrun with all manner of corporate operations and condos that don’t make it a “hipster haven” so much as a yipster’s paradise. This is not a Brooklyn where people are thrilled to buy jars of cucumbers pickled by rainwater–there would be far too much of an outcry about sanitation from the uppity ilk that, in the movie, are gung-ho about Herschel’s simplistic (read: crude) enterprise.

The only reason he’s decided to start a pickle empire is to prove to Ben how “stupid” he is with his now rejected BoopBop endeavor, and to buy back the grave plot Sarah (as well as Ben’s parents, David and Susan) is buried in, disgusted that it’s been overtaken by a looming “Cossack” billboard for vodka. Determined to make the $200,000 required, Herschel doggedly sets about his quest, another factor that heightens just how undetermined the modern generation is, waylaid by even the slightest inconvenience whereas our forebears took it as par for the course. Wouldn’t even know how to function if something wasn’t practically death-inducing to achieve. As Ben watches his ancestor’s success unfold on social media, he finds his own ambition (to put a kibosh on Herschel’s prosperity) taking hold, calling the health department on his great great g-pa to shut him down. As it is said, no one can get under your skin like a family member, and that is just what Herschel and Ben do to one another as newly sworn enemies in a competition called: Who Best Represents the Greenbaum Name.

Here, again, we have something that is most especially specific to the New York school of thought–believing you have to accomplish consecutively escalating amounts of “success” (i.e. acquiring more and more financial wealth, therefore clout) through your family name. Just look at the Trumps as a shining example of how ugly such a New York school of thought can become. And, in Herschel’s case, that ugliness radiates as well, driving him to do horribly mean-spirited things to his own kin in the name of showing him “how it’s done.” “It” being to bring honor to a family name by way of fame and fortune instead of doing something that might genuinely make one happy.

The increasing absurdity of the narrative reaches a peak when Ben ends up back in Herschel’s former town thanks to a bit of conniving from the latter. While some might say the mounting hijinks are what temper the movie from getting too schmaltzy, the undeniable saccharine taste lingers as the credits roll more than any flavor of brine. Particularly when Barbra Streisand makes her own, let’s say, “roundabout” cameo. Of course, in the annals of the “men frozen in time and sent to the present” genre (including Les Visiteurs and Encino Man), it’s not the worst offering.