When you reach a certain level of “icon status,” there is no coming back from being subjected to “the right” people feel they have to pillaging and dissecting your “essence.” “Who you are” and “what you mean.” Marilyn Monroe, née Norma Jeane Baker, has perhaps been one of the most shining twentieth examples of this (apart from Britney Spears, who borders on the cusp between centuries). Unlike Madonna, someone equally as behemoth in iconic stature (and who has spent most of her career emulating Marilyn in some way or another), Monroe never had that aura of strength that Ciccone built her own success on with songs like “Over and Over” and “Express Yourself,” both anthems of empowerment. Indeed, despite occasionally being positioned as a “feminist” beacon, Monroe’s career was centered entirely on playing up her vulnerability, characterized by a certain “daffiness” that made her a master of screwball comedy gold (e.g., Monkey Business, How to Marry A Millionaire and Some Like It Hot).

Something she couldn’t break away from once she established herself in the dumb blonde archetype that 20th Century Fox’s studio head, Darryl Zanuck, never wanted to free her from. Which is part of why she fled to New York to found Marilyn Monroe Productions with Milton Greene (only to give us the somewhat lackluster Bus Stop as proof of her more “profound” acting abilities). Of course, none of this is acknowledged in the “reimagining” or “fictionalized account” of her life that is the movie version of Joyce Carol Oates’ 2000 novel, Blonde. In contrast to this massive tome (totaling 738 pages), Andrew Dominik’s adaptation does the opposite of what Oates’ work had intended: exploitation for its own sake. While Oates wanted to hold up a funhouse mirror to the world (or at least to those who read) of how grotesquely it objectified Marilyn, Dominik’s version of the work ends up instead having the same effect as another recent Netflix outing, Dahmer—Monster: The Jeffery Dahmer Story (or, just Dahmer, to make it easier). Grotesquerie for the sake of it.

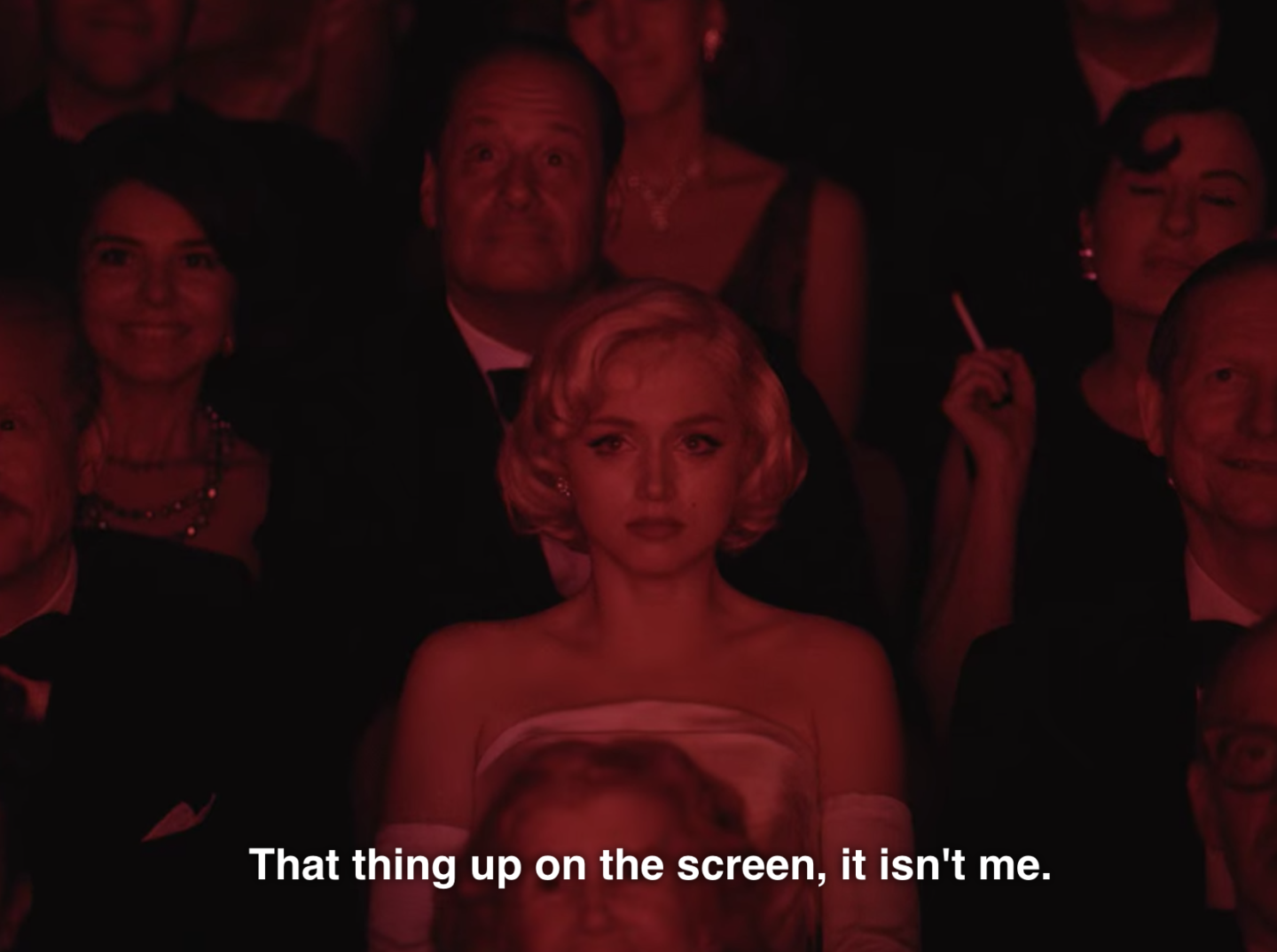

Of course, there are moments when Dominik remembers he’s supposed to be showing society—specifically, male society—how lecherous it is under the pretense of being “poised” and “conservative.” “Superior” to those “out-of-control” and “baitingly whorish” females. The very ones that Monroe typifies. Hence, the warped appearance of men in the crowd ogling her with open mouths that become cartoonishly large (the same type of facial effect occurs in Madonna’s “Drowned World/Substitute For Love” video when everyone around her is nothing more than a pair of hungry eyes [“manga eyes,” if you will] waiting to snap a photo, to appraise her). This occurs at the premiere of Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, which Marilyn watches in saddened horror, musing on what her father would think of her as she says internally, “Oh Daddy, that thing up on the screen. It isn’t me.” And neither is the version of Marilyn being played by Ana de Armas, who frequently often comes off like she’s playing Nicole Kidman playing Marilyn Monroe. She even looks a bit like Kidman compatriot Naomi Watts in certain lights, which makes sense considering, at different times during the initial phases of production, both Watts and Jessica Chastain were going to be cast for the part.

But Dominik must have wanted to tamper with Monroe’s image further by going with a non-white actress. Which is, quite possibly, better than an Australian actress trying to carry it off. And, sure, there are many scenes where de Armas looks like a “dead ringer,” but, for the most part, all the viewer can see is: Ana de Armas. Who was not the best casting choice for the role. The best person that comes to mind for it, actually, is Florence Pugh. What’s more, it seems another sign of disrespect (in addition to being played by a Cuban actress, who swears up and down that Marilyn haunted the set—probably because she didn’t want this trash made) to the woman, the myth and the legend to have a male writer-director adapt this story.

Maybe that’s part of why, throughout the duration (a clunky and slightly surreal three hours—because that’s what happens when you try to adapt a 738-page opus), all one can wonder is: why? What is really the purpose of this film apart from wanting to achieve what Dahmer does—horror-delight of the spectacle—by turning a woman who was already made into a distorted exhibition her entire life (and after-life) into an even greater one. And all, ultimately, as a showcase for de Armas. Because it certainly isn’t one for Dominik, who picks and chooses all the wrong elements to feature in the movie, though, for those first few childhood minutes at the beginning, it appears as though he might actually follow the timeline trajectory Oates laid out in the book, right down to her mother, Gladys (Julianne Nicholson), driving toward one of those quintessential, raging L.A. fires instead of trying to keep young Norma Jeane safe from it.

In truth, the aspect most grounded in reality is Gladys’ erratic, irascible nature. Granted, there’s never been a well-documented incident of her being the one to try to suffocate Norma Jeane—that was instead attributed to her grandmother, Della, with a pillow. Della being another character that Dominik arbitrarily chooses to omit from Norma Jeane’s early years, along with her adoptive parents, modeled after Ida and Wayne Bolender. The couple in the book seems to like Norma Jeane well enough at first—but then the fictional version of Wayne starts to like her a little too well, as far as Ida’s concerned, prompting her to push Norma Jeane into marrying a slightly older man named Bucky Glazer (the literary version of NJ’s first husband, Jim Dougherty).

Norma Jeane sees this push out of their home as another form of rejection, but goes along with it to evade the risk of being sent back to the orphanage at such an “old” age (fifteen). Thrust into the arms of Bucky, her issues with abandonment intensify again when he decides to enlist in the army despite all her best attempts to be the “perfect little wife.” Excluding this from the narrative also detracts from highlighting the genuine and constant sense of neglect Norma Jeane felt, pushing her toward pursuing “Hollywood acceptance” by starting to earn a living in Bucky’s absence through posing for magazine pictures that subsequently lead to a contract deal.

And still another missed opportunity (for Dominik’s intent to twist and warp the actress’ life, in which case, one would have a better time watching Harley Quinn briefly play her in Birds of Prey) is Norma Jeane’s commitment to Christian Science (practiced by both her mother and Aunt Ana). The irony being that she would end up going in the totally opposite direction with her drug dependency. Surprisingly enough, the one cheap, exploitative shot Blonde doesn’t opt for is a rape scene (well, apart from the extremely brief one in “Mr. Z’s” office), which occurs in more than implied form during her marriage to Bucky. This plays into the fact that Marilyn herself wasn’t that interested in sex. Didn’t get the enjoyment from it that men would expect of someone who was a sex symbol. This also ties into her long-standing bout with endometriosis, a primary contributor to Monroe’s frequent miscarriages, including an ectopic pregnancy in 1957.

Undoubtedly, Marilyn’s lack of “motherly” predilections were part of what ended up rubbing Joe DiMaggio the wrong way—he who wanted an acquiescent homemaker over a “slut” posing as a “career girl.” That much goes out the window when Bobby Cannavale, meant to be playing DiMaggio (another “meh” casting choice)—although that name is never expressly used—is approached by Marilyn’s former lovers, Charlie Chaplin Jr. (Xavier Samuel) and Edward G. Robinson Jr. (Evan Williams), with nude pictures of her that prompt him to let his hot-headed tendencies get the better of him as he rushes home to smack her and declare, “These photos. That’s what you are. Meat.” “I don’t want to be,” she replies. Yet, at her core, some part of her did. The part that wanted to be loved and admired at any cost because she was deprived of it for so long. The part that knew the score when it came to “playing the game” by giving all the Hollywood perverts what they wanted: her body. And she still gives it to them, even now, via a twenty-six foot “spectacle” in Palm Springs that’s actually less crass than this movie.

She was definitely playing the game with her talent agent, Johnny Hyde, the man after whom “I.E. Shinn” (Dan Butler) is partially based on. But, for whatever reason, their dynamic isn’t sexual in Blonde, with all the focus placed on the made-up relationship between her, Cass and Eddie. A plot point underscored, obviously, for the “salacious” cachet of it. After all, Dominik himself stated of making the movie, “I’m not concerned with being tasteful.” That much is made evident on multiple occasions throughout Blonde, not least of which includes the scene of her getting violated by “Mr. Z” (the overt “pseudonym” for Darryl Zanuck). While many actresses were subjected against their will to Zanuck’s notorious casting couch, Marilyn was not. She climbed the ladder in other sexual ways, primarily as an escort to “important men,” like Joseph M. Schenck—the man who would talk Harry Cohn into giving her a contract. She was doing this around the first time she met Arthur Miller, who was in town with Elia Kazan. Miller probably got it into his head then that he would “rescue” her someday. Because that’s ultimately what everyone wanted to do for Marilyn, and part of why she was so “inexplicably” fascinating.

Even to someone as overtly disinterested in her work as Dominik. Naturally, as a person who admitted to never having seen any of Monroe’s movies until being given the gig of directing Blonde, he might not have the best insight into her “personage.” Nor did it give anyone a boost of confidence about his credibility after he foolishly stated that Marilyn’s canon is comprised of a “whole lot of movies that nobody really watches.” If that were the case, it wouldn’t be so upsetting to see her image denigrated the way it is in Blonde. Dominick also added, in stupid asshole form, “She’s somebody who’s become this huge cultural thing in a whole load of movies that nobody really watches, right? Does anyone watch Marilyn Monroe movies?” Sounds like a person who should really be making a film about Monroe. Luckily, his interviewer for Sight and Sound, Christina Newland, corrected his extremely dense presumption by responding, “I do. A lot of my colleagues and friends do. Gentlemen Prefer Blondes is one we watch a lot.” To further dig his own grave, Dominick asked, “Really? What is it about?” Newland replied, “It has a worldview that is quite cynical about men and gender relations in a way that I think a lot of contemporary young women like. And it affords Marilyn’s character of her wit, she gets one upmanship on men. She’s not a dumb blonde, really.”

But Dominik, nor any of the men who came before him, have ever really seen her beyond the surface. At least not beyond the surface of how they could manipulate and wield her story for their own ends. For Dominik, the view is not Oates’, but rather, his own, seeing the book from the perspective of being “an unloved child. I relate to it.” Bitch, this ain’t about you. Instead, he claims, “…in the end, it’s about the book. And adapting the book is really about adapting the feelings that the book gave me.” Uh no, wrong again. Adapting the book is about not obliterating an already controversial fictionalization for the purposes of one man’s “vision” or “interpretation” of it. Yet Dominik had the gall to say, “I think the film is about the meaning of Marilyn Monroe. Or a meaning. She was symbolic of something. She was the Aphrodite of the twentieth century, the American goddess of love. And she killed herself. So what does that mean?”

It means men like Dominik not only drove her to death in life, but have found new ways to kill her in death. “Killing,” after all, can come in so many forms, not least among them being exploitation. Something that DiMaggio would refuse to do (unlike her second husband, Miller, who most blatantly exploited Monroe’s “psychosis” in After the Fall). Instead, he never spoke about her in public and famously had a half-dozen red roses sent to her crypt three times a week for twenty years. He also banned the so-called Hollywood “elite” from attending her funeral, including any member of the Kennedy family. Remaining hopelessly devoted in a “gentler” way that he could not achieve during their short-lived marriage, he never remarried. In Blonde, when he’s finally calmed down a bit after back-handing her, he tells her, “I can’t bear to see you cheapen yourself like that.” But, alas, she has been cheapened regardless. If nothing else, by non-virtue of this very film posing as some monstrous “arthouse” rendering of her life.

And it’s not as though it says anything new about the beloved bombshell, for even that 1996 made-for-TV (except, “It’s not TV. It’s HBO.”) movie, Norma Jean & Marilyn, starring Ashley Judd and Mira Sorvino in each respective role made a big to-do about how Marilyn was a construct, nothing more than part of Norma Jeane’s bifurcated self, that “magic friend” in the mirror who had all the confidence she never did. So it is that “Marilyn” is consistently referred to as “another” in Blonde. The alter ego Norma Jeane drags (“Marilyn” herself being pure drag) out so she can be unanimously loved. For it’s true that one has to be a “certain kind of person” to end up in show business—the kind who was starved of love in some way as a child. Starved enough to “debase” herself. As she’s made to do in the very-fictionalized-indeed account of her being in a throuple with Charlie “Cass” Chaplin Jr. and Edward G. Robinson Jr. In real life, the latter appeared in the Monroe movies Bus Stop and Some Like It Hot and dated her after Charlie Jr.—not in conjunction with him. In Monroe’s made-up Blonde life, it’s in acting class where, mysteriously (and to add to the overall surreal quality of the movie), Charlie and Eddie are the only two students in attendance.

The trio grows close quite quickly, calling themselves collectively “The Gemini” (even though Eddie was a Pisces and Cass was a Taurus). As for the homoerotic bond between Eddie and “Cass,” the former describes it as, “We’re juniors…of men who never wanted us.” Cass then tries to make Marilyn’s orphan scenario sound like a dream to her by saying, “You can invent yourself. I love your name. It’s so totally phony. Like you gave birth to yourself.” According to the Juniors, she’s “free”—precisely because she doesn’t have a father. Marilyn, of course, doesn’t concur, spending her whole life in search of a father figure to replace the “Daddy” she never had.

Maybe that’s why she possesses no discernment when it comes to calling all her lovers “Daddy,” including DiMaggio and Miller (Adrien Brody—and yes, imagine the joy Brody must have felt when he was told, “You know who you look just like?”). In Oates’ Blonde, neither of these men are actually named, referred to instead as the Ex-Athlete and the Playwright. Perhaps Oates, in her own way, wanted to better avert her chance of being sued, who knows? Both men and their remaining kin being so “touchy” about the subject of Marilyn. As everyone is—whether those who adore her or those who view her as an “overblown” actress who was in few movies of worth (like Dominik).

To justify playing “fast and loose” with his own interpretation of Oates’ interpretation, Dominik asserted, “For me it was just the scenes I found compelling. I went with my instinct and wrote it pretty quick. And I didn’t change it that much, even though it was sitting around for fourteen years. I know the ways in which this is different from what people seem to agree happened. Not that everyone’s sure. Nobody really knows what the fuck happened. So it’s all fiction anyway, in my opinion.” What a post-truth, post-reality thing to say. Along with, “Does anyone care, really? People who make films tend to think they’re incredibly important. But it’s just a movie about Marilyn Monroe. And there are going to be a lot more movies about Marilyn Monroe.”

It seems, however, that no one should want to make or see another movie about her after this atrocity. Which only proves that she’s more plunderable than ever with the passing of time. Almost as though it’s allowed people to totally forget that she was a real person, with the type of traumatic life that stood out even among the dime-a-dozen traumatic backstories of Old Hollywood actors of the day. But it’s almost as though Dominik wants to take advantage of her increasing lack of “personhood”—made manifest earlier this year by Kim Kardashian shoving her ass into Marilyn’s once iconic Jean-Louis dress. The one she wore to sing “Happy Birthday, Mr. President” to JFK at Madison Square Garden. And, speaking of JFK, the nadir of Blonde is probably the scene of Marilyn sucking said president’s dick (complete with the heavy-handedness of a rocket ship on TV becoming erect), basically forced to do so by the latter in a cold and clinical way as one of his advisors warns him about his sexually predatory nature soon coming back to bite him in the ass.

As far as Dominik’s love of “fucking with perception,” there’s an instant where Norma Jeane’s indelible mole a.k.a. beauty mark appears on the opposite side of Marilyn’s usual cheek, as though to emphasize that nothing about Monroe is remembered accurately. And that she was always “playing to the camera.” All of her “put-ons” done in a way that suits whoever “consumes” her.

And yet, if one was hoping for some kind of “pithy” reason behind why Dominick chose to alternate between color and black and white for the movie, they’d also be disappointed. It has nothing to do with, say, the metaphor of blurring between movie fantasy and dreary reality, but rather, as Dominick puts it, “There’s no story sense to it. It’s just based on the photographs. So if a photograph was, you know, four by three, then we do it four by three. There’s no logic to it, other than to try to know her life, visually.” Which we already do, so honestly, what the fuck?

We also knew about Billy Wilder’s notorious contempt for Monroe during both movies he directed her in, but most especially 1959’s Some Like It Hot, when Monroe had reached a new apex of drug cocktail dependency. Yet, the main issue was not that she scratched her face and screamed at Wilder (which is what happens in Blonde), but that she often didn’t show up at all. And when she did, it was to slur her speech and show off her inability to memorize a simple line like, “Where’s the bourbon?” In Blonde, Norma Jeane’s beloved makeup artist and confidant, Whitey (Toby Huss), appears at her house afterward to assure her after this flare-up with Wilder, “I’m going to conjure Marilyn within the hour, I promise.” Because there it is again: the big “profundity” of the movie—that Marilyn isn’t real. She’s just this “thing” Norma Jeane created to function in a man’s world and a man’s industry.

One that remains so, as Dominik has made clear by claiming this story as his own and remarking, “My films are fairly bereft of women and now I’m imagining what it’s like to be one.” Please don’t. Or, if you must, try harder. For this is not Oates’ vision (though she inexplicably praised a rough cut of the movie in 2020), this is not anyone’s vision (other than those who wanted to see de Armas with her tits out…de Armas included). It’s just a runaway train of desecration.

In that sense, the most accurate thing said by “Marilyn” in this entire movie is, “What business of yours is my life?” A question that should have been posed to Dominik sooner.