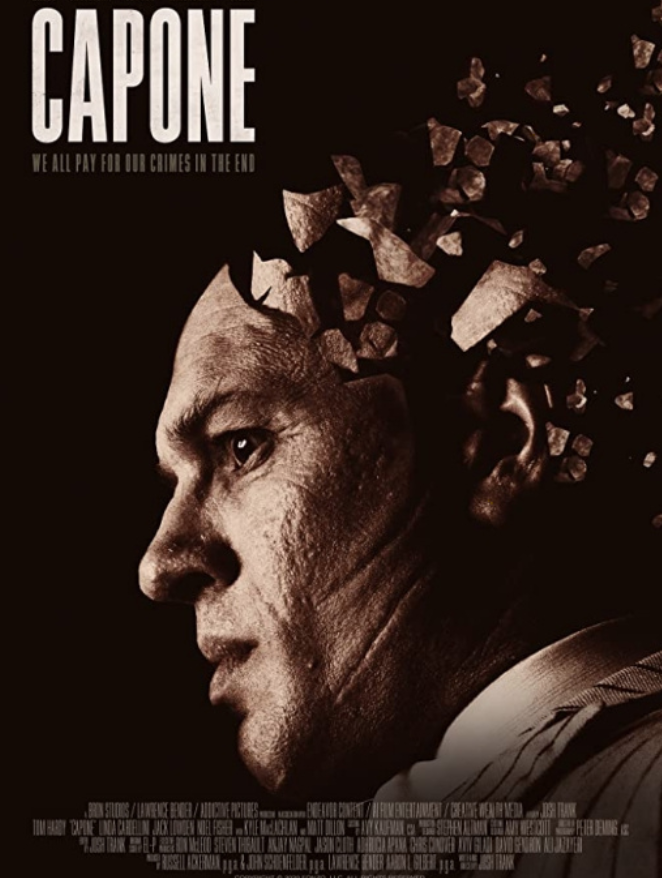

When it comes to movies about criminals, particularly of the Italian-American mafioso variety, there is never a shortage. Least of all on the subject of Al Capone, who remains, to this day, one of the United States’ most illustrious gangsters, alongside other purebred Italians who immigrated to America, including Capone’s mentor, Johnny Torrio, Carlo Gambino, Frank Costello and Lucky Luciano (born Salvatore Lucania). The crimes and elaborate subterfuge of men like these in an era when lawlessness wasn’t quite so goddamn trackable has created an entire genre of film: the gangster movie. But what hasn’t been explored before in the annals of gangster movie history is the decay and demise of a man once deemed a leviathan of the underworld (The Irishman doesn’t quite count, as it focuses on an entire life). Perhaps taking a page from the Judy book, which also focused solely on the last year of Judy Garland’s tragic life, writer-director Josh Trank (coming out of the woodwork of Fantastic Four five years on) has opted for a different approach to Capone’s relatively short existence, one that emphasizes a notion that, as the tagline says, “We all pay for our crimes in the end.”

And how might Capone pay for the bloodshed he wrought beyond the rather minimal prison sentence he served for tax evasion (perpetuating the Benjamin Franklin adage, “…in this world nothing can be said to be certain, except death and taxes”)? Why, with the deterioration of his syphilitic mind, of course–making the possibility for a hallucinatory narrative about Capone coming to terms with the many men he killed in his life all the more possible, and plausible. Of course, the primary critique of the film, apart from Tom Hardy’s incoherent dialogue, has been that it’s “too haphazardly constructed”–yet that would seem to be the entire point of conveying the “thought process” behind a paranoid aging gangster with neurosyphilis. “Paying for his crime in the end” might have also referred to the ironic karma of penicillin becoming a viable treatment for syphilis in 1947, the same year Capone died. But no, there would be no treatment for Capone’s degenerating condition, no matter how princely the environs of his Palm Island, Florida castle. The one filled with the sort of tacky statues (which he is forced to sell off) one imagines Gianni Versace likely made a better go of at his own Floridian mansion, Casa Casuarina, in Miami Beach. Or the private screenings of major motion pictures, namely The Wizard of Oz (going back to the aforementioned Judy parallel), which likely reflected back to any of Capone’s remaining brain cells something of his own constant mind-bending experience. Unable to tell the real from the decidedly psychedelic. Or, in short, living through the plot of A Christmas Carol every day as he’s visited by ghosts of wronged people past.

Only these visitations aren’t going to change his present, let alone what little is left of his future. They are simply part of his minimal comeuppance in comparison to the carnage he brought about. Even if under the guise of “giving the people what they wanted.” Indeed, before the notorious St. Valentine’s Day Massacre (re-created for more comedic effect in Some Like It Hot), Capone was rather well-liked by the public, and was, of course, in bed with both the Chicago police and Mayor William Hale Thompson (elected in part thanks to Capone’s henchmen gunning down voters for the other candidate), all of whom profited from Capone’s violently cultivated bootlegging and racketeering business. But after that massacre in 1929, the year that the Roaring Twenties and Capone’s clout would come to an end, he became Public Enemy No. 1 (one of his many nicknames among Scarface). As one of the violent acts that would come to define him the most, it makes sense that Trank would render Capone’s regular hallucinations to feature a re-playing of the event on an imagined radio broadcast that never quite seems to get the story right. The inherent guilt he seems to feel leads his family members, including his wife, Mae (Linda Cardellini), who has stood by him through it all for some inexplicable reason, to refer to him as “Fonse” (another diminutive of his Christian name, Alphonso) instead of Al–his murdering moniker.

Trank also provides no paucity of eerie, flashback-esque chimeras that include “Blueberry Hill” performed a capella by Louis Armstrong (Troy Anderson) at a New Year’s Eve celebration in which everyone cheers for Al’s arrival. He’s the king. And the Cowardly Lion, always getting others to do his bloody bidding. As we see in a subsequent scene in which one of his goons, Gino (Gino Cafarelli), brutally stabs a tied up Johnny in the neck like he’s cutting up a rare piece of meat (this image, too, is contrasted against that particular murder).

Hardy, meanwhile, does his best to make the most of a role where it isn’t really words that are said, so much as grunts and shoddily accented stock Italian phrases… in between fits and starts of a tyrannical rage usually resulting in falling down or having some kind of stroke (and let us not forget the grossest scene of all, Capone–titan among titans–shitting himself in the bed). This is not a movie about a Goliath of a crime lord, but a man cut down to size in all of his frailty, diminished once again to the same nobody he despised being in his Park Slope youth, this very station in life being what kept escalating his gangster behavior for the sake of amassing more wealth, ergo power. A lion who would become king of the Chicago jungle. Indeed, the fitting use of the Cowardly Lion is wielded with parallelism perfection. For it is this character that Capone seems to identify with most in the movie, informing his former associate, Johnny (Matt Dillon)–as in, presumably, Johnny Torrio, which Trank seems to believe Capone had a hand in killing in this revisionist history–that he needed courage at all costs. The question subtly posed throughout is: does it take courage or cowardice to kill so ruthlessly?

Tellingly, The Wizard of Oz (which came out in 1939, as the world was slowly emerging from The Great Depression thanks to the start of WWII) and the Cowardly Lion both keep coming up to iterate a point. He could have been king of the forest, sure, but what would it matter without the courage necessary to maintain that throne? The Wizard of Oz’s place in history, specifically in Capone’s, feels like a salient nod to the fact that it came at the end of another decade, therefore era. One that was, in contrast to the 1920s that made Capone famous, a period of all-out destitution. Without Capone there to illegally bring joy to the masses. The Wizard of Oz, with its vividness and colorful depiction of a fantastical world, was all the more appropriate for mirroring a population that was slowly beginning to believe there might be hope for brightness again. Unlike Capone, whose candle burned so blazingly for a single decade that it could only get dimmer and dimmer in the aftermath.

Imprisoned in his prime, at the age of thirty-two, Capone would spend the rest of his life in a state of deterioration, at least part of which might have been prevented had he sought treatment for the syphilis he contracted at a brothel circa 1919. While penicillin was not yet invented, at the time, Salvarsan might have been an effective enough remedy to mitigate Capone’s eventual downward spiral. But so it goes with men who think themselves to be gods, always believing they’re immune to an inevitable fall.

For a life so filled with exploits, hijinks and constant excitement, Capone’s reduction to an invalid incapable of anything other than racking his diseased brain to try to remember if he really did hide ten million dollars somewhere that his family might be able to use after his death is what makes the semi-biopic effective. Proves that perhaps 1) there really is such a thing as cosmic justice and 2) growing up in abject poverty tends to make one reach for stars that might only poke his eyes out in the long run. Capone, while a polarizing movie for its unique approach to a man’s story so frequently scripted, underscores these exact morals through the delusions and discomforts of a gangster one wants to believe was at least mildly contrite for his actions. Then again, that’s probably just another cinematic machination.