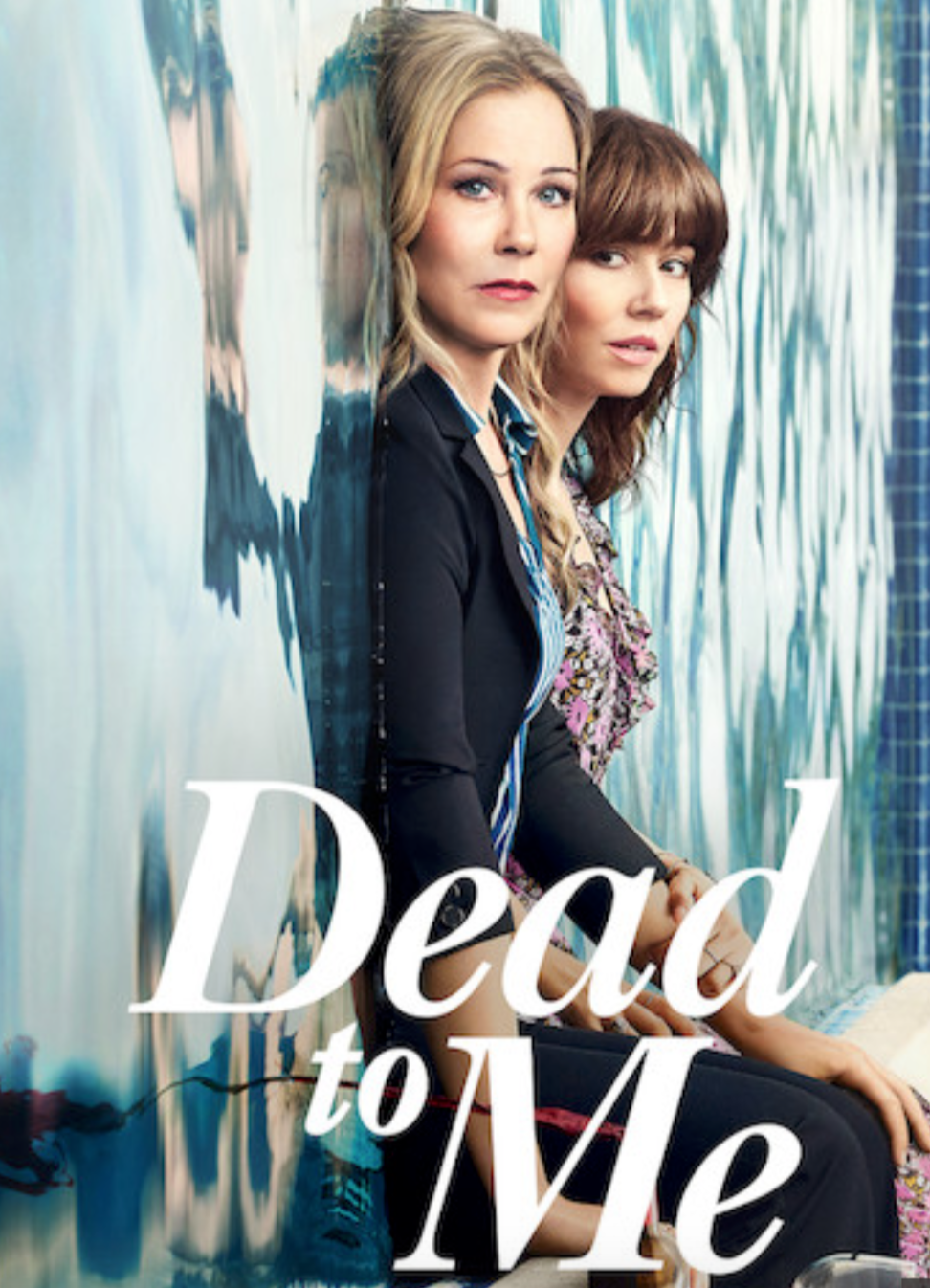

When you’re young, friendship forms rather easily, seemingly apropos of nothing. There isn’t discernment beyond being in the same age group. That is, until the age group in question morphs into middle age and it is suddenly realized just how much time one wasted on little assholes for the sake of filling the silence. Netflix’s latest series starring Christina Applegate and Linda Cardellini, Dead to Me, riffs off this concept in many ways in almost an inverse manner to age group bonding: trauma bonding. Specifically at a grief support group where successful Laguna Beach realtor Jen Harding (Applegate) and assisted living facility worker Judy Hale (Cardellini) strike up a rapport–albeit an initially rocky one as Jen is an impenetrable force to be reckoned with.

Luckily (or perhaps not, as the viewer soon comes to find), Judy is not squeamish in the face of Jen’s hard as nails persona, which is not a front, as some like to say about people of this nature. Offering her number if Jen ever wants to talk through the hit and run that happened to her husband during a moment of insomnia, Jen weakens to the prospect after going through all the phases of grief throughout her lengthy night. It is with that phone call, during which Judy lies about having lost her own significant other–fiancé Steve Wood (James Marsden, who must have cut the same deal with the devil as Jared Leto to still look pretty fucking young)–that their friendship is lightly cemented. But it’s a cementing that is ripped from the ground when Jen learns Judy isn’t who she claims to be, pulling up to the house where she saw Judy standing in front of with Steve in a picture she shared with her, only to have the door answered by supposedly deceased Steve himself.

Exhibiting her rage in all of its glory, Jen shows just how imprudent it is to incur the capabilities of her wrath as she publicly exposes Judy’s lie to the group. Though select members are surprised, hearing Judy tell her side of the story makes them accuse Jen of being too harsh. For Judy technically has known the loss of grief via her five miscarriages–the last one finally prompting Steve to leave her (though there is, of course, a much larger element at play). Jen slowly cools down long enough to be able to forgive Judy for her fucked up and unnecessary lie and the two are soon back toward the well-paved path of that cemented friendship. So well-cemented, in fact, that Jen invites Judy to live in her guesthouse after finding that she’s been holed up at the assisted living facility that she works at. Steve having cruelly kicked her out (and Jen, in a fit of anger, suggesting that she lets him list his house so that Judy can’t stalk him anymore). So yes, from friends to roommates, as it were.

It is in episode four, “I Can’t Go Back,” that Steve, who has rescued her from jail after Judy takes the fall for Jen bashing in the car of someone she sees speeding all the time, reminds her, “What kind of friendship is based on lies? And manslaughter?” Judy returns, “A layered one?” And maybe there’s something to that naively plucky response. For there are so many areas of gray as the show unfolds that it’s impossible to fathom what we ourselves would do in both Jen and Judy’s extremely unusual positions.

Upon learning that one of her most beloved charges, Abe (Edward Asner), at the home she works in has died, Judy is not only sent further over the edge emotionally but, in one final gesture of showing her love for him, goes to his funeral. As a Jewish man, Abe’s service is presided over by a rabbi who moves Judy to ask what their prayer meant, the answer boiling down to one of the tenets of Judaism that largely distinguishes it from Christianity: the belief that there is no heaven or hell. Therefore, that we must spend what we have of this life trying to rectify our sins unto others before we leave this earth. “Making amends,” as the rabbi calls it. In essence, Judy has been trying to take this approach in her inexplicable, completely-against-the-norm-of-what-is-societally-acceptable decision to befriend Jen despite being the one who killed her husband (it’s not a spoiler, okay? It’s in the official summary of the show and quickly revealed at the end of episode one).

Her hippie-dippy California ways aside (saging the guesthouse, of course, included), Judy genuinely believes that she must serve a purpose in Jen’s life to have entered in this most unfortunate way. And as the trauma bonding of this traumedy heats up literally in episode five, “I’ve Gotta Get Away,” when the duo decides to go on a Palm Springs “grief retreat,” Judy has very clearly gotten into the spirit of embracing just how much so many people get off on their pain. From “Man to Man Yoga” to “Carry On-oke” (with Yolanda [Telma Hopkins] fittingly singing Thelma Houston’s “Don’t Leave Me This Way”), Judy is inspired to see how many ways there are to heal from grief, none of which Jen wants to partake of as she continues to process the knowledge of Ted’s affair from the previous episode. Part of that processing comes in pursuing a widower as Judy embarks upon her own retreat romance after hearing Nick (Brandon Scott) sing “Drive” by The Cars, which triggers some more flashbacks to her running over Ted. So yes, an interesting way to be “enthralled” by someone. Then again, Judy’s issues with codependency spur within her a natural need to please, so even if she’s not particularly interested in Nick in that way, once he gives off the vibe that makes Judy think he is, she kind of goes with it. And of course she still wants Steve. Because like her great TV character before Judy, Lindsay Weir (and her lust for similar shithead Daniel Desario [James Franco, still pretending to play it more straight]), she just can’t say no to a pretty face, no matter how cruel the mouth on it can be.

With Steve’s gradually interwoven narrative (mimicking the same elaborate puzzle that Abe has been working on for weeks at the rest home), Dead to Me is both provocative and avant-garde in terms of how it treats female friendship, which can, believe it or not, transcend mindless chatter and competitiveness over looks as they pertain to “catching a man.” And Steve himself isn’t even your average douche bag misogynist, cleverly concealing that side of himself much in the same way he does the true sources of his financial prosperity. As he comes face to face with Judy in a confrontation in the final episode, he uses the standard gaslighting technique all narcissists can’t resist by belittling, “Don’t turn this into some ‘blame the man thing.'”

Funnily, that’s all Jen wanted to do as she thought endlessly of finally capturing Ted’s killer, who she naturally assumed to be a man. It is in episode eight, “Try to Stop Me,” that Jen admits, “I never pictured it being a woman. What kind of feminist am I?” Nick, by now Judy’s full-time gentleman caller and conveniently a detective (“on leave”), reminds, “Women can be murderes too.” Jen quips, “I know, I saw that Charlize Theron movie.” Nick barbs back, “Which one?” They both chuckle together as apparently Theron likes murderous roles that help remind fake feminists like Jen that women can be murderers too. Not just dick chopper offers.

As everything comes to a tense crescendo and Jen is faced with the jarring truth about Judy, Dead to Me presents a never before seen version of how two women can fail the Bechdel test while still sharing a profound and meaningful friendship.