In the early 90s, Hollywood was becoming more self-aware of its own ageism. Perhaps in a manner not seen since Billy Wilder’s groundbreaking 1950 film, Sunset Boulevard. The first movie of its kind to truly lambast “the biz” in a manner that had never been done before. So damning, in fact, that the luminaries of Hollywood were not ready for it, with Louis B. Mayer reportedly yelling at Wilder, “You bastard! You have disgraced the industry that made you and fed you! You should be tarred and feathered and run out of Hollywood!” In the wake of its release, other “anti-Hollywood” movies would follow, including 1952’s The Star, with Bette Davis in the lead role that smacked of Norma Desmond (Gloria Swanson) in terms of the whole “aging, irrelevant star clings to former glory that can never be recaptured” angle. Tellingly, the movie came out eight months after Singin’ in the Rain the same year (as did The Bad and the Beautiful, the story of an insufferable producer named Jonathan Shields [Kirk Douglas]). This, too, being a condemning tale of how fickle and merciless the industry is when it comes to tossing out “irrelevant women” without a second thought. After all, movies aren’t about making “art” (contrary to the MGM saying, “Ars gratia artis” a.k.a. “Art for art’s sake”)—they’re about the bottom line.

Perhaps the industry didn’t want to allow an entire genre to be carved out about itself right away, because it wasn’t really until the 90s that self-referential movies of a meta, satirical nature started coming out again. 1992 being the year of both The Player and Death Becomes Her. Then there was Swimming With Sharks in 1994, the tale of a dastardly movie mogul named Buddy Ackerman (the then socially acceptable Kevin Spacey) and the new assistant he abuses daily. Barton Fink and Bowfinger would provide bookends to the decade as well, each coming out in 1991 and 1999, respectively. Additionally, Hollywood provided the mid-90s “romp” Get Shorty and, two years later, another pièce de résistance of the genre via 1997’s L.A. Confidential. But out of all of them, Death Becomes Her was the most tailored release vis-à-vis addressing the lengths a woman feels she must go to in order to stay looking “forever young.”

Of course, a resurgence in self-mockery didn’t mean Hollywood was actually going to do anything about its ageist proclivities in terms of making a significant change—a.k.a. rendering the industry as more friendly to the “aged.” To be clear, in Hollywood, “aged” means pretty much any number over thirty. Even to this day. The only thing women, actresses or otherwise, have on their side at the moment is the advancement of various anti-aging “remedies” (i.e., expensive creams and/or plastic surgery). But even those “tactics” tend to end up doing her a disservice as she can be equally as ribbed for her attempts at looking younger (see: the malignment of Madonna after her 2023 Grammys appearance). As Madeline Ashton (Meryl Streep) is by the time we reach the midpoint of Death Becomes Her. On her last legs as a “viable” (read: fuckable) actress, her long-time frenemy (but really just enemy), Helen Sharp (Goldie Hawn), comes to see her at the beginning of the film, written by Martin Donovan and David Koepp, and directed by Robert Zemeckis. Because perhaps no one understands better than men just how much women are valued for their youth and looks above all else.

Commencing in 1978, Death Becomes Her wastes no time in introducing its audience to the rampant ageism not only against women in general, but women in the entertainment industry in particular. Zemeckis sets the scene on Madeline’s opening night performance of Songbird!, a Broadway adaptation of Tennessee Williams’ Sweet Bird of Youth (in truth, one wonders if Williams didn’t get his own inspiration from Sunset Boulevard). The irony here being that the part of Alexandra del Lago a.k.a. Princess Kosmonopolis was written for Tallulah Bankhead, who would have been fifty-four years old when the play first came out in 1956. Not exactly the “age group” Madeline would want to be associated with, and yet, a job is a job.

After the audience lambasts her as they walk out, with such commentary as, “Madeline Ashton! Talk about waking the dead,” we’re given a glimpse of her supposedly cringeworthy (no more than usual for something meant to be set in the 70s) performance before Zemeckis cuts to her in her dressing room, staring at herself in the mirror as she reworks a famed lullaby into: “Wrinkled, wrinkled little star…hope they never see the scars.” Her lament over watching her youth fade is augmented tenfold as a result of being damned to see that youthful version of herself forever immortalized onscreen. Constantly making her yearn to be that girl again, as opposed to appreciating what she had when she had it. The same parallel can be found in Norma Desmond, with her boy toy/hired personal screenwriter, Joe Gillis (William Holden), observing the way she watches herself so lovingly onscreen. This prompts Joe to remark in a voiceover, “…she was still sleepwalking along the giddy heights of a lost career—plain crazy when it came to that one subject: her celluloid self.” The only “real” self, as far as Norma (and her delusions) is concerned.

But Madeline isn’t so naïve. The Hollywood of the 70s and beyond would hardly allow her to be. Which is why she knows that when Helen reemerges after a seven-year disappearance from the public eye to throw a book party (taking place in then-present 1992) that Madeline’s been invited to—very deliberately—she’s fully aware she needs to look her best. Knows that it’s an opportunity to prove, once again, that she’s “superior” to Helen, if for no other reason than because she’s still “the hot one.” What she can’t fathom is that the entire motive for Helen to put on the fête is because she wants to parade just how amazing she looks and how well she’s doing to an ever-dwindling-in-importance Madeline (reminding the latter of as much when she tells her condescendingly at the party, “Gosh, I’m glad you came. I didn’t know if you would. I spoke to my PR woman and she said, ‘Madeline Ashton goes to the opening of an envelope’”).

Even before arriving and realizing that she’s been outdone aesthetically by Helen, she senses the urgency of needing to go to her med spa and seek another treatment. But when her “specialist” refuses to give her the procedure she wants again so soon and instead offers a collagen buff, Madeline retorts, “Collagen buff? You might as well tell me to wash my face with soap and water.” Trying her best to keep her customer calm, the aesthetician then offers to do her makeup. Madeline balks, “Makeup is pointless! It does nothing anymore!” Not for “mature skin,” as it’s “politely” called in the world of foundation and concealer. She then verbally lashes the youthful aesthetician with, “You stand there with your twenty-two-year-old skin and your tits like rocks!” In other words, this bitch couldn’t possibly understand what Madeline is going through (but oh, how she’s going to). The scent of Madeline’s desperation is evidently potent enough for Roy Franklin (William Frankfather), the owner of the spa, to materialize out of nowhere in the same room and slip her a business card that contains only an address in elegant script: 1091 Rue la Fleur. Never mind the fact that L.A. doesn’t have French street names, the decision to name it after a flower is entirely pointed. After all, flowers are frequently used as metaphors (especially in poetry) to represent the “budding” of a girl’s youth (a gross phrase, to be sure) followed by the eventual decaying of that bloom. The one that makes her ultimately repugnant to men (and women) of all ages.

Even so, Madeline persists in doggedly ignoring this reality—able to do so with the perk of having enough cash to pay a boy toy…à la Norma Desmond. Dakota (Adam Storke), however, is growing weary of Madeline’s cloying nature. This much is apparent when she shows up at his door unannounced looking for false comfort in the wake of Helen’s book party. Unfortunately for her self-esteem level, she finds that he’s with another (younger) woman. When she acts upset about it, he finally snaps, “I’m sick of this shit, you know that? I am doing you a favor here.” She asks incredulously, “Doing me a favor? I gave you—” “Yeah, you gave, I gave. Big deal! Somebody told me we look ridiculous together. How do you think that makes me feel? You never think about my feelings. Go find someone your own age, Madeline!” If Joe Gillis had been a colder sort, he might have said the same thing to Norma…except he knew all too well of her suicidal inclinations at the drop of a hat.

With Dakota’s scathing rejection being the last straw, Madeline gives in to going to the address she was slipped at her med spa. A house that belongs to one, Lisle von Rhuman (Isabella Rossellini). To Madeline’s surprise, Lisle is already expecting her, having her muscular lackeys invite her in and then diving into her philosophical ruminations on aging, such as, “We are creatures of the spring, you and I… You’re scared as hell—of yourself, of the body you thought you once knew.” The one that’s changing and mutating like some kind of cruel science experiment. As Iona (Annie Potts) in Pretty in Pink laments, “Oh, why can’t we start old and get younger?” (otherwise known as: Benjamin Button’s disease).

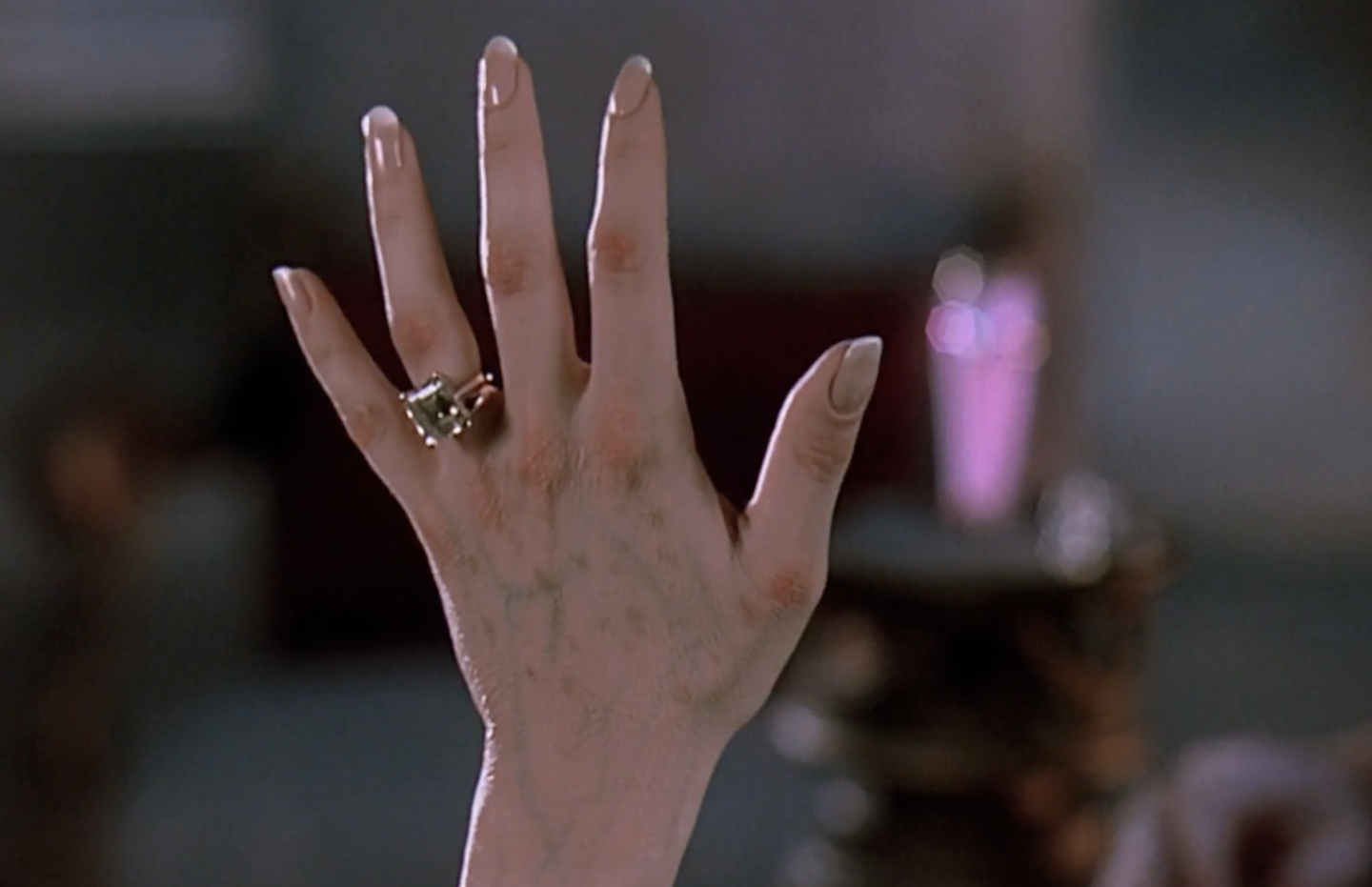

Lisle continues to make strange overtures as she caresses Madeline’s hand and muses, “So warm, so full of life. And already it ebbs away from you. This is life’s ultimate cruelty. It offers us the taste of youth and vitality…and then makes us witness our own decay.” With no amount of money ever being able to truly stave off that degeneration.

Even our early forebears couldn’t help but be concerned with aesthetics amid basic survival concerns, considering the first plastic surgery procedures have been documented all the way back to ancient Egypt. And that’s really saying something when taking into account the lifespan for most people at that juncture. A majority was prone to dying young, with the average life expectancy in ancient Egypt being nineteen years old (which certainly meets the “die young” criterion presented in the book and movie version of Logan’s Run). Richies, like the pharaohs, however, could typically count on a longer lifespan (quelle surprise), usually between thirty-five and forty years old. And obviously, they would want to look their best while outliving the hoi polloi. There is something to be said for that same desire in the celebrity set, our modern version of the pharaohs, one supposes. They, too, are youth-obsessed for the same two-pronged reason: 1) being in the public eye means perpetual scrutiny/people seeking out flaws as a means to belittle the work itself and 2) they want the commoner to understand that they are not the same. Even if, as some would like to speculate, “I don’t think people want perfection out of celebrities anymore. I think they want celebrities that they can see themselves in.”

But truthfully, the fact that Death Becomes Her remains as pertinent now as it ever was is a testament to that theory being another lie some prefer to tell themselves. That the film has also become a cult classic in the queer community additionally speaks to the gerascophobia of the gays. Per Peaches Christ, who has remade Death Becomes Her as Drag Becomes Her, “Let’s face it, gay men especially have this issue. It’s actually a real issue. It’s a real darkness in our community where we don’t talk a lot about the ageism that exists among us. And it’s a real thing.” But let’s not get it twisted: no one has it worse than women when it comes to aging and being cast out by (male-dominated) society as a result. So obviously, Madeline and Helen would take the potion offered by Lisle, regardless of what the potential ramifications might be—which is that they effectively turn themselves into non-bloodsucking vampires.

While Helen’s motives for doing it stem largely from her competitive history with Madeline and wanting to prove that the only thing Madeline ever had as an advantage is her looks (now fading), Madeline’s drive to take the potion is emblematic of what spurs most actresses (and pop stars). They’re all clamoring to remain seen (as they were) amid fresher, newer “talent” entering the fray. And “being seen” has only become even more of a challenge in the attention span-decimated present. As for Ernest (Bruce Willis), who the duo tries to convince to take the potion as well so that he can patch them up for eternity (he’s a plastic surgeon-turned-reconstructive mortician), he doesn’t want anything to do with immortality. Thus, he tells Lisle, “I don’t wanna live forever. It sounds good, but what am I gonna do? What if I get bored? What if I get lonely? Who am I gonna hang around with, Madeline and Helen?” Lisle sticks to the crux of the sales pitch by reminding, “But you never grow old.” Ernest bemoans, “But everybody else will. I’ll have to watch everyone around me die. I don’t think this is right. This is not a dream. This is a nightmare.” Or, as the first verse of Thomas Moore’s “The Last Rose of Summer” goes, “‘Tis the last rose of summer,/Left blooming alone;/All her lovely companions/Are faded and gone;/No flower of her kindred,/No rose-bud is nigh,/To reflect back her blushes/Or give sigh for sigh!”

So sure, staying young and vibrant has its pluses, but, in the end, caving to vanity means you’ll end up stuck with someone as narcissistic and soulless as the Hollywood machine itself. And the way Madeline and Helen end up in the final scene, it doesn’t appear as though the price they’ve paid for “youth” has been worth the fine-print consequences.