“Why do people get so sentimental about old people? They’re arseholes,” says Derry girl Michelle Mallon (Jamie-Lee O’Donnell) at the funeral of Erin’s (Saoirse-Monica Jackson) vicious Aunt Bridie (Eleanor Methven). Remarking upon this when she and the crew are all trying to keep the old people in question from consuming any of the edibles that have just been confiscated by Sister Michael (Siobhan McSweeney), the stern headmistress, of sorts, at their Catholic school, it is the first sign angling toward pointing a finger at the fraught state of Britain in the present. Thusly would Britain’s current windbag prime minister seem to be proving Michelle’s point with the erratic, out of touch behavior of the old guard in considering the well-being of a nation whose future ought to be built with the present youth in mind.

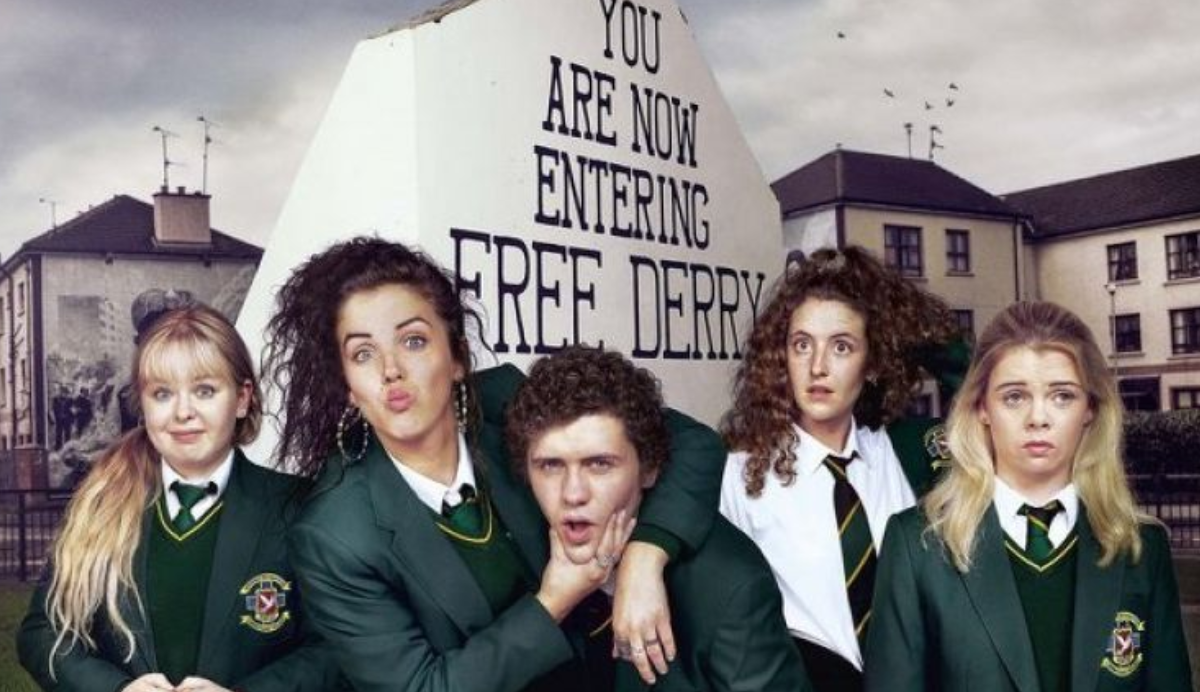

As the show has progressed from its plucky aloofness to the bombs and guns of the mounting Troubles of Irish civil war (for it’s merely the norm, after all), the Derry girls comprised of Erin, Michelle, Orla (Louisa Harland), Clare (Nicola Coughlan) and honorary Derry “girl” James (Dylan Llewellyn)–Michelle’s hopelessly mainland British cousin–can no longer be quite so enmeshed in the business of being 90s teens just the same (something that reaches a zenith when they go to Belfast to see a Take That concert).

This much becomes apparent in the series finale of season two (the show has rightfully been renewed for a third season), which writer and creator Lisa McGee very deliberately chooses to set during Bill Clinton’s historic visit to the town in the wake of a peace declaration. No longer can Aunt Sarah (Kathy Kiera Clarke) write off the inconvenient presence of a bomb on the bridge as a nuisance that might prevent her from getting to her tanning bed session. For yes, though the president’s arrival causes many blockades, it is an event that represents the culmination of all that previous chaos the denizens of Derry were all so wont to ignore.

The fact that James chooses to attend Our Lady Immaculate Girls School with his cousin for fear of getting beat up at the boys school “because of the English thing” is a testament to the lengths of avoidance this gang will go to in order to disregard all evidence pointing to death and destruction. On a side note, James incurs the wrath of the girls regardless when he deigns to go on a tirade about how disgustingly greasy their fish and chips are, getting him kicked out of their favorite eatery as a result.

Throughout the series, one of the key points of nostalgia speaks to the 90s phenomenon of “bleeding heart” charities and organizations every child of the decade will remember being advertised on TV. With Clare going on about fasting for a child in Ethiopia in the pilot episode or the Our Lady Immaculate Girls School welcoming the “Children of Chernobyl” as they host a group of students from the contaminated area to “breathe in some fresh Derry air” (yes, that sounds innuendo-laden), the decidedly 90s trend of helping others so as to make one feel better about themselves is pervasively comical throughout the series.

Along with the requisite jokes about the Catholic-Protestant divide that has spurred much of England in general and Derry specifically’s tensions. For anyone familiar with the history of Derry knows that the religious schism traces back many centuries, when the Siege of Derry in 1689 found William III of England’s supporters holding out against James II’s Catholic supporters for a total of 105 days. The event is still commemorated to this day by the Apprentice Boys of Derry (notice there are no mention of girls in the title to indicate being so petty about the whole affair). With Northern Ireland’s formation into a separate state in 1922, Catholics were the overt majority in Derry. This was no match for the gerrymandering power of the Protestants, who took control of the government regardless. All this deeply rooted bad blood, however, is hilariously written off in “Friends Across the Barricade,” season two’s premiere episode. Tasked by their school with meeting up with “rivals” at a Protestant school, the Derry girls and their fellow students are asked to come up with even one thing that Protestants and Catholics have in common. In the end, it turns out to be parents. It’s an especially 90s angst-ridden sentiment that Angela Chase could get behind.

And, speaking of Angela Chase, the episode entitled “Ms. De Brun And The Child Of Prague” is not only a riff off the Dead Poets’ Society effect that a “new teacher”/substitute can have on their class, but also bears a strong resemblance to the My So-Called Life episode, “The Substitute,” in which, similarly, an educator that inspires in school is not so inspiring when viewed within the context of their personal life.

While McGee is careful to make the coming of age themes of Derry Girls feel universal, the distinctiveness of what it means to be Northern Irish shines through at every turn, as the clan does its best to avoid the traffic of the Orange parades or Erin and her friends get swept up in doing a dance to Hues Corporation’s “Rock the Boat” at the wedding in “The Curse.”

Yet most salient of all–well, almost as salient as the show’s soundtrack itself, punctuated by the likes of Whigfield and The Cranberries (obvs)–is McGee’s decision to conclude season two on November 30, 1995, when Clinton momentously arrived in town, causing a far greater frenzy in Derry than constant news of bombs going off. And as Clinton was introduced by John Hume with the highlight on Irish-American ties, therefore making his presence not one’s standard instance of American showboating, it was reminded that “thousands upon thousands of our people left to emigrate and lay the foundations of Irish America… Our links with America are powerful and strong” (just watch Brooklyn again to remind yourself). As such, the U.S.’ interest in the peace of Ireland was not a total non sequitur. And, in the spirit of JFK–mentioned several times in the episode–Clinton would take the stage to tell the people of Derry, “This city is a very different place from what a visitor like me would have seen just a year and a half ago. Before the ceasefire. Crossing the border now is as easy as crossing a speed bump. The soldiers are off the streets, the city walls are open to civilians. There are no more shakedowns as you walk into a store. Daily life has become more ordinary, but this will never be an ordinary city.”

No, so it would seem not with its endless hard-won charm, even if Erin and her friends have big dreams to leave it one day, maybe even for America, at that point in time not such an overt hellmouth. Clinton goes on to say, “The deep divisions, the most important ones, are those between the peacemakers and the enemies of peace. My friends, everyone in life at some point has to decide what kind of person he or she is going to be. Are you going to be someone who defines yourself in terms of what you are against, or what you are for? The time is come for the peacemakers to triumph in Northern Ireland.” Clinton then goes on to further butter up the town by citing Brian Friel’s play, Philadelphia, Here I Come!, remarking, “It’s all over and it’s about to begin” with regard to the end of an era and the beginning of a new one. So it goes for the Derry girls as well, faced with the potential loss of one of their own, and realizing just how important “she” is to them. So important, in fact, that even after Clare fights to the death for a spot up front near the podium, the lot of them surrender it without a second though to run back to their friend up above triumphantly shouting, “I’m a Derry girl!”

At the same time, Bill’s speech begins at its conclusion as he urges, “And so I ask you to build on the opportunity you have before you, to believe that the future can be better than the past. To work together because you have so much more to gain by working together than by drifting apart. Have the patience to work for a just and lasting peace.” How that comes to pass in the Derry girls’ world could likely come in the form of the advent of the “Macarena” by season three.

Ultimately what “The President” episode iterates about Derry Girls is that, although a comedy on the surface, much of the narrative is a more than subtle knifing at the notion of history repeating itself. Except, in this case, it’s difficult to feel the emotional ties of nostalgia to the present, so lacking in anything to sentimentally cling to other than Lana Del Rey’s early career. Hence, maybe it is with the winsome perspective of Derry Girls that the Brits can start to get a clue from that nearby island they once undercuttingly helped fight against the IRA, and maybe understand themselves better in the process. Because, whether you’re from Londonderry (this name being yet another source of contention and debate) or not, like everything else, “Being a Derry girl, it’s a fucking state of mind.”