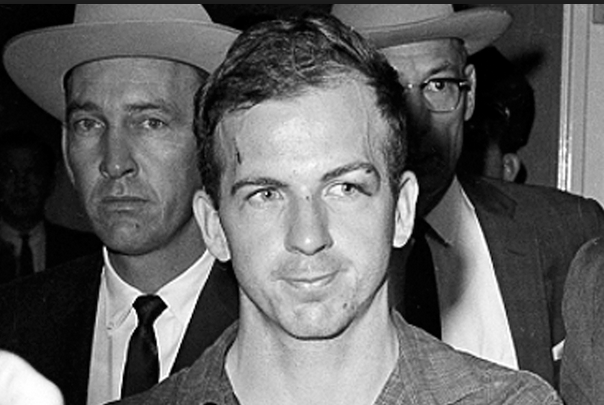

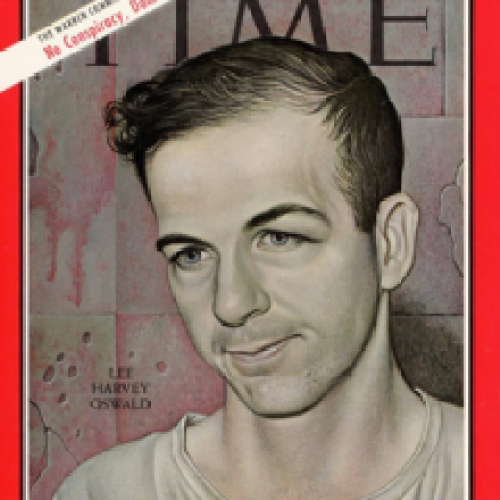

As an antisocial child who spent most of his youth being shuffled around and, ultimately, deemed a truant by the school system, Oswald grew up without a father figure and was prone to a fantastical imagination. DeLillo focuses heavily on Oswald’s childhood and, later, his defection to the USSR. Before this life-changing move, however, Oswald enlisted in the Marine Corps at seventeen years old. His brother, Robert Oswald Jr., acted as his guardian in signing the consent forms that would allow Lee to gain entry into the Marines.

It isn’t until DeLillo highlights Oswald’s time in Russia, however, that Libra becomes its most interesting. For someone who always felt like an outsider in his own country, Oswald seemed to believe that styling himself as a foreigner would somehow make him feel more at home. His allegiance to communism also showcased a proclivity for indoctrination–a factor that may have contributed to Oswald’s later cajoling into killing Kennedy (if this is, in fact, what happened). To his dismay, Russians were even more averse to him than Americans. Entangled in an elaborate web of deceit that involved playing both sides and appealing to the U.S. and USSR governments at different times depending on his purpose, Oswald seemed increasingly to be without a concrete identity.

It isn’t until DeLillo highlights Oswald’s time in Russia, however, that Libra becomes its most interesting. For someone who always felt like an outsider in his own country, Oswald seemed to believe that styling himself as a foreigner would somehow make him feel more at home. His allegiance to communism also showcased a proclivity for indoctrination–a factor that may have contributed to Oswald’s later cajoling into killing Kennedy (if this is, in fact, what happened). To his dismay, Russians were even more averse to him than Americans. Entangled in an elaborate web of deceit that involved playing both sides and appealing to the U.S. and USSR governments at different times depending on his purpose, Oswald seemed increasingly to be without a concrete identity.

His impromptu marriage to a Russian pharmacology student named Marina Prusakova proved almost as sudden as his decision to return to the United States and settle in the Dallas-Fort Worth area. Here, DeLillo picks up the pace of laying out the series of events that would lead to November 22nd. For as monstrous an act as Oswald committed, DeLillo’s conclusion to the novel is almost tender in its depiction, with Oswald’s grieving mother, Marguerite, attending a deserted funeral.

The title of the novel, too, is rife with astrological implications. Oswald, who was, of course, a Libra represents some sort of ironic imbalance in the annals of history–in spite of Librans possessing a sign that is supposed to infer the ultimate in fair and balancedness. Instead, Oswald’s scale tipped in favor of depravity. Or was he a victim of his own fate? This theory would presume the conspiracy aspect of Oswald’s involvement in the shooting, a mere pawn of the government, mafia and anyone else who wanted Kennedy out of office. DeLillo sums this up best in the final pages of the book:

“If we are on the outside, we assume a conspiracy is the perfect working of a scheme. Silent nameless men with unadorned hearts. A conspiracy is everything that ordinary life is not. It’s the inside game, cold, sure, undistracted, forever closed off to us. We are the flawed ones, the innocents, trying to make some rough sense of the daily jostle. Conspirators have a logic and a daring beyond our reach. All conspiracies are the same taut story of men who find coherence in some of criminal act.”