Maybe it is because Lamb immediately establishes itself in something like a far-off universe—Iceland—where Ingvar (Hilmir Snær Guðnason) discusses time travel now being a possibility and half-human, half-lamb hybrids are born without much fanfare that we can believe in the reality co-screenwriters Sjón and Valdimar Jóhannsson present us with. And clearly, it’s an overt parable for the reality we actually live in. One in which humans take whatever the fuck they want from Mamma Natura without much fear of the consequences. Which, as it’s been made repeatedly evident, will be increasingly dire. Unfortunately, it takes the lid blowing off someone’s own house for them to really believe.

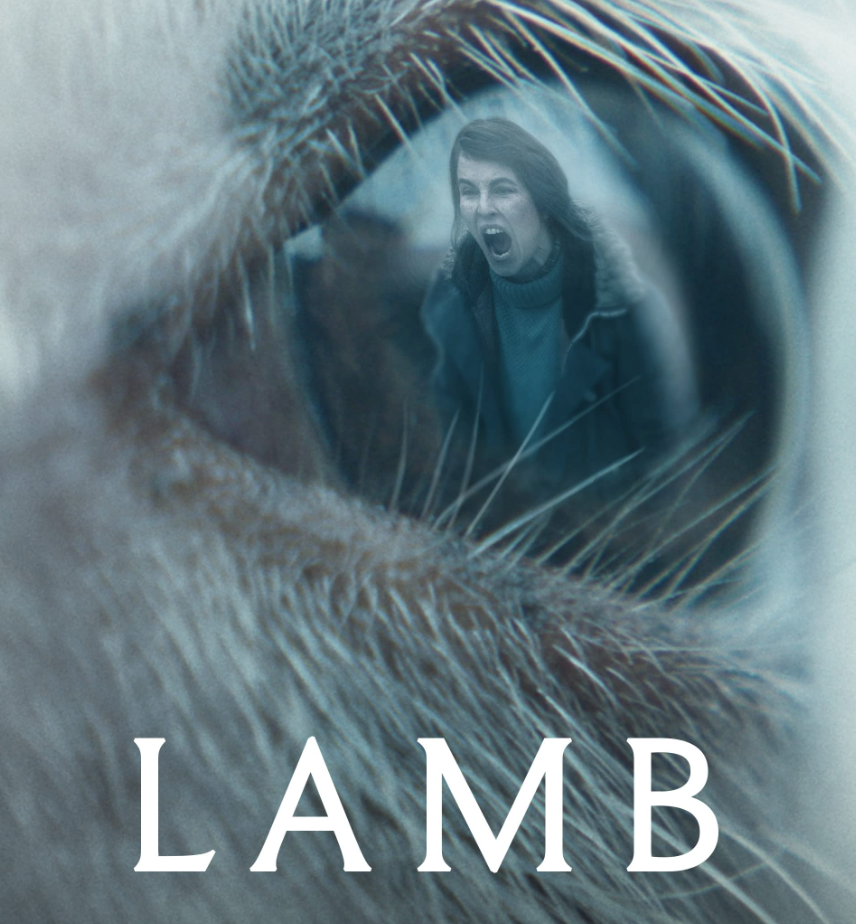

Just as it takes María (Noomi Rapace) a few personal cataclysms to understand that no good can come of plucking “Ada,” as they come to call her, from her mother. A very protective ewe who isn’t so quick to just let her little lamb go—even if that lamb is very different indeed. For, after director Jóhannsson opens the film on a foggy hill on Christmas Eve (adding some biblical flair to the lamb’s birth), we see that what we’re looking at is from the perspective of a moving predator stalking toward a herd of spooked horses. Standing in the haze, they don’t need to fully see the creature to know they ought to be threatened—nor do we. And that’s what’s so effective about Lamb: the fact that we don’t see the half-man, half-ram hybrid that has his way with a ewe in the barn to create “Ada.” Whose name, creepily enough, is derived from María and Ingvar’s dead daughter. Needless to say, they’re trying to substitute her with this “gift” they see fit to give themselves despite the irrefutable fact that it—she—belongs to her real mother. And to Mother Nature. Speaking to that introductory moment, many subsequent scenes in the film promote the use of fog—a vapor that permeates the area as a mirror of the clouded judgment humans seem to have when it comes to their dealings with nature.

That Ingvar and María live on an isolated farm certainly helps fortify the delusion they’ve created. A self-made bubble that insists it’s perfectly natural that 1) a half-lamb, half-human exists at all and 2) that they should raise it as their own human child… seemingly more content that it cannot speak their language. What they view as a picturesque idyll is only interrupted twice. The first instance being when Ada’s mother, that persistent ewe, keeps coming up to the window where María has placed the crib. Crying out for her baby, Ada, too, seems to yearn to go back to her—that is, before she becomes too domesticated and seems to forget all about her core identity as an animal (much like humans are able to with the artifice provided by jobs and houses). María is sure to make Ada forget by coldly murdering the ewe after one too many interruptions that set her off. She’ll be damned if she’s going to be harassed by anyone threatening to take “her” baby. And she is, of course, damned. As all humans are when they decide they can go up against the natural world and order. Which will always come back to claim its “vengeance” by simply restoring that order.

Much to María’s dismay, the second intrusion upon her bliss with Ada comes in the form of Ingvar’s brother, Pétur (Björn Hlynur Haraldsson). Down on his luck, he happens to show up in the night seeking shelter just in time to witness María killing the ewe. Being clever enough to hold onto that information, he doesn’t lord it over María until the time comes when he wants to leverage it to extract a sexual favor from her. Because, yes, apparently they had an affair in the past that he keeps wanting to rekindle. María, on the other hand, just wants to focus on her “family.” Repairing the emotional damage caused by the loss of her human child with this new one. But Pétur is quick to remind both of them, “It’s not a child, it’s an animal!” This exclamation perhaps an undercutting commentary on how humans treat their domestic animals more and more like children. Ingvar is quick to shut down his brother’s “naysaying”—meaning any mention of the objective reality. That’s sort of how many humans are able to function in the present climate, wherein the sky is falling, but so long as we don’t talk about it, it’s not (a major premise in Don’t Look Up).

Pétur is not so quick to accept their “rules” as he feeds Ada a clump of grass to remind her of her true self. Her animal instincts. Still vexed by her very existence living as a human, Pétur takes her out into the field and tries to shoot her while María is asleep, but even he can’t bring himself to decimate that adorable face. Elle est simplement trop précieuse. And it’s a preciousness meant to embody all of Nature. How can any of us, when we stare directly into its face, be so cruel toward it? Again, unless you’re María competing with a ewe. Or a corporation determined to make more profit.

As the ominousness of it all builds with the kind of quiet horror that A24 has made itself known for, the karmic balance comes back to bite María in the arse when the ram-man returns to reclaim the child that is now, more than ever, rightfully his—what with the ewe having been slaughtered and all.

At a certain moment toward the end, Ingvar grabs the hoof side of “his” baby, while the ram-man grabs the hand side of Ada for an inverse twist. The symbolic permutation is highly effective in conveying that, indeed, something has gotten very twisted up and out of sorts in this thing called post-Industrial Revolution life. With the only “revolution” really occurring being the one in the fat cats’ wallets as they seek to destroy every last bit of Earth for profit. All under the new guise of doing it “greenly.” But, whatever the greenwashing would like to brainwash the masses with via “feel-good” advertising, there can be no “environmental-friendliness” so long as capitalism endures.

Accordingly, Lamb is the environmental allegory we need to pay attention to now more than ever, as we continue to fuck with nature in ways that will come back far more than thrice. COVID-19 itself being one such example of what happens when humans keep encroaching upon animal territories merely because, well shucks, they feel like it.