The “gap years” between each Baz Luhrmann film have grown longer over time. Made obvious by the statistic that Luhrmann has “only” directed six movies in the span of thirty years. But when you watch each one—their sweeping depth, their attention to every detail, the music—it becomes evident why he needs to take his time. Elvis is no exception to the rule. And, with the eponymous singer being such an iconic and problematic figure (the latter quality addressed in certain ways while glossed over in many others), Luhrmann’s brand of “putting a sheen on things” is perhaps the most well-suited approach for such a delicate subject as “The King.” Unless one were opting to go the full-tilt #MeToo angle on Elvis’ notorious antics with women, and especially his would-be child bride, Priscilla (who herself often has some blind spots about the inappropriateness of the relationship). But no, that’s not what this film is. That can perhaps be reserved for some other auteur to tackle. A female one, preferably (but not Greta Gerwig… ideally, Issa Rae).

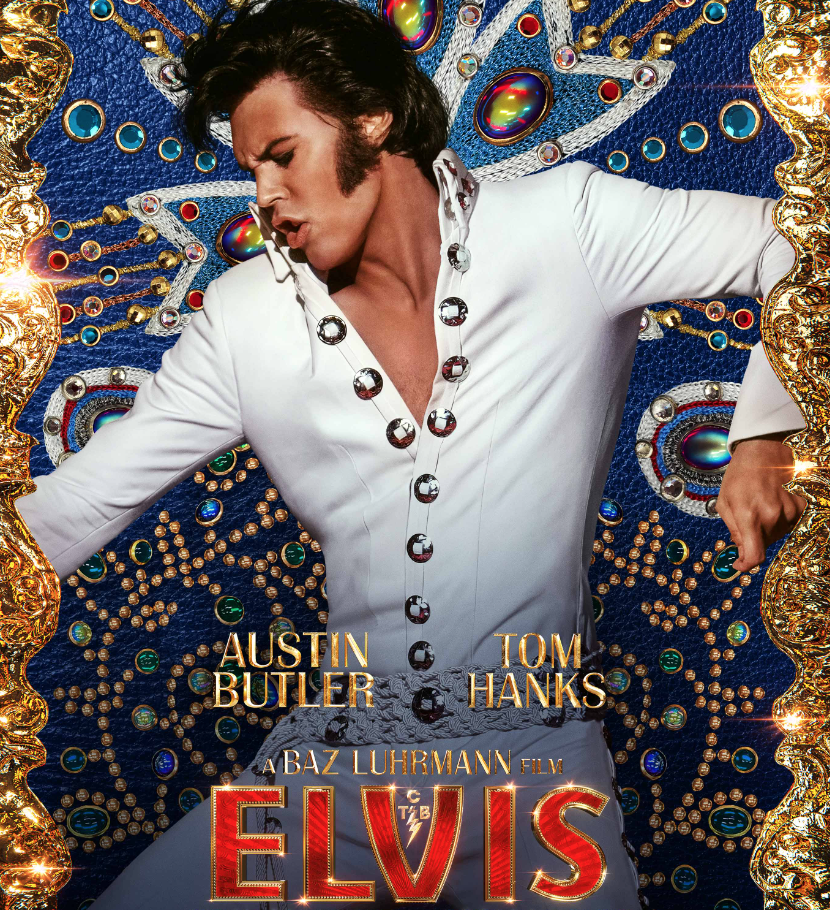

It makes sense to go this “serious Hollywood production” route after so many films about Elvis that have either been parody-like or Lifetime-like. In the former category, Tom Hanks had already orbited the Elvis realm by playing a bit part in 2004’s Elvis Has Left the Building. No match for the likes of Bubba Ho-Tep, in which Bruce Campbell plays Elvis in a retirement home (for, in the novella it’s based on, he fakes his own death to start over without any leeches on him). The point is, there are so many approaches to Elvis. And the easiest to take in the modern era is one that pokes fun at the caricaturized identity that came to roost with the Las Vegas residency. With Luhrmann’s sweeping biopic, a sort of Moulin Rouge meets The Great Gatsby where music and aesthetics are concerned, the legend is both fortified and debunked. For no one has ever tried to tell the gigolo-pimp story of Elvis and the Colonel. Luhrmann, who co-wrote the script with Sam Bromell, Craig Pearce and Jeremy Doner, is also certain to make his audience aware of just how much Elvis, like his fellow 50s icon, Marilyn, signaled a complete cultural shift in Western society. A zeitgeist was afoot, and Elvis was the conduit for manifesting it completely.

The question of his being overly influenced by “Negro music” was what made him political from the start. He was a clear symbol for a bevy of hotbed issues ranging from America’s flagrant white supremacy to appropriation. Regarding the latter issue, Elvis says to B.B. King (Kelvin Harrison Jr.), “I’d love to record that” while watching Little Richard (Alton Mason) perform “Tutti Frutti.” King replies, “You’d make a lot more money recording it than he would.” It’s a brief and small concession to the uncomfortable subject of Elvis’ legacy of, to put it mildly, “grafting.” A conundrum in terms of whether or not Black people should be “grateful” Elvis stole their sound and made gobs of money from it (at least for a while before the Colonel kifed it all). Because, on the one hand, without Elvis—a white man—to spread the literal Gospel of Black music, would change ever have come as “quickly” in America? Would the undeniable influence of Black culture and its saturation into “white culture” (apparently so nonexistent that it usually needs to take “aspects” of what it likes from others) have served as a catalyst for and backdrop to the revolution of the 60s? It’s a dangerous question to ask, mainly because the blunt answer is so unpleasant. And yes, there are many who say that Elvis certainly wasn’t the first Southern white boy to rip off blues, Gospel and folk to make it more “country” (read: cracker-friendly). That he was merely at the right place at the right time. Then again, maybe it was quite the opposite based on encountering the shyster that would become his lifelong warden.

But to write Elvis off only as being “lucky” would be to ignore his indelible talent. Like the majority of artists, Elvis cared most about the art itself. Which is perhaps why he “left the details” of money to the Colonel and his father, Vernon Presley (Richard Roxburgh). The latter being complicit in the squandering of his son’s funds in acting as Elvis’ so-called “business manager.” It was Vernon, in fact, who unwittingly spurred Elvis to become famous in the first place. Wanting to be the “superhero” that would save his family from poverty and the shame of his father being an ex-convict, Elvis took it upon himself to become the breadwinner by any means necessary. Somebody who could be the protector—and also buy his mama a pink Cadillac, to boot.

In an archival interview that appears at the end of Elvis, he remarks, “When I was a boy, I always saw myself as a hero in comic books and in movies. I grew up believing this dream.” This being at a point in his career before he tells Priscilla during his Vegas phase, “I’m all out of dreams.” One of the many hazards of achieving just about everything you ever wanted too soon. Well, almost everything. For he never did get to make that James Dean-esque movie worthy of an Oscar nomination or take that tour overseas—all because of the Colonel’s manipulations about “security risks” when, in truth, the only reason he declined the overseas tour offers was because he wouldn’t have been able to go thanks to being an illegal citizen in the U.S. with no passport to speak of.

Although the Colonel was the more grotesque one, Elvis was treated like a sideshow by his manager from the start. He was, once again, only going to do what he did best: be a barker. Shouting out “come one, come all” at anyone who might pay to get into the tent. But Elvis, for as much of a gigolo as he transcends into for the Colonel, has his limits now and again. Reaching a threshold when he knows he’s lost too much of his edge (as is the case when he played “Hound Dog” in coattails on The Steve Allen Show, at the encouragement of the Colonel, naturally).

Another “foot down” moment on his artistic integrity comes in 1968, just before his Christmas special (filmed in June, when RFK was assassinated) will be taped. At one point, Luhrmann lays the metaphor of Elvis’ washed-up persona on real thick when he sets a scene of “The King” having a secret meeting with the producers of the special, Steve Binder (Dacre Montgomery, who might have been able to play Elvis himself) and Bones Howe (Gareth Davies), behind the increasingly dilapidated Hollywood sign. Sitting inside one of the letters, Elvis remarks that that’s how a lot of things are nowadays—broken, rundown, decayed. It alludes to the nonstop series of tragedies and assassinations that occurred in the precarious decade that made Elvis come across as even more irrelevant for relying solely on “cheesecake” movies during which he was ostensibly content to play a parody of himself. All at the advice of the Colonel, who promised the Republican G-men Elvis would be a “good boy,” reformed once he served a tour of duty in Germany. This after being berated by conservatives as “Elvis the Pelvis” and an “infection” upon the “Good Morals of the White Person” with all that “Negro devil music” sullying the ears of white-bread Americans.

The only person less interested in this “deal” to leave America than Elvis is his mother, Gladys (Helen Thomson, though the role was originally going to be played by Maggie Gyllenhaal). Already equipped with a nervous drinking habit (sort of like Kirsten Dunst in The Power of the Dog), it ramps up when “her boy” gets too far away from her clutches. Her phobia of losing a son stemming from the death of Elvis’ twin brother at birth (hence the lore that Elvis was given the strength of two men). So it is that the drink drives her to an early death before Elvis even gets back. Indeed, without being sent to serve in the army, Elvis’ mother might not have died prematurely, therefore the Colonel might never have been able to take such a hold over his life. But, by the same token, had he not gone to Germany, he also never would have met “Air Force brat” Priscilla Beaulieu (Olivia DeJonge). So yeah, a real “sliding doors” moment (minus the part where things turn out the same regardless of the path taken).

The Colonel’s machinations to remake Elvis into a “clean-cut” persona having failed in music, he sets his sights on nothing but one cornball picture after another for Elvis to churn out once he returns to the States. Always most concerned with the profit potential rather than the artistic one. What’s more, because it remained the Wild West days of the music industry, complete with payolas still reigning supreme, managers—a relatively new phenomenon—could get away with so much more abuse. As The Beatles’ own manager, Brian Epstein, showed us as well. But Epstein, at the very least, was someone who loved, appreciated and understood music. Whereas, like Hanks noted of the Colonel, “He does not have an artistic bone in his body. He does not care about the output of his one client, Elvis Presley.” Nor did he ever care to admit to contributing to Elvis’ early demise. Case in point, during an interview in the 80s for Nightline, the Colonel made a rare later-in-life appearance to lie through his teeth, “I know one thing: when I told us to slow down, he said I wanna play more dates so I booked us more dates. I said, well I don’t think you should and he said well that’s what I wanna do.” The “snowman” spinning his yarn till his dying breath. Which, incidentally, is where Elvis commences.

Starting from the end of the Colonel’s life—most of which was spent skulking around casinos gambling away the fortune he had stolen out of Elvis’ pocket—he reflects on his first encounter with Elvis, and “just knowing” (after being assured that the kid wasn’t Black) that Presley was going to be his meal ticket. Some say there would be no Elvis without the Colonel, but surely another person would have come along to manage him sooner or later. Perhaps someone less bloodsucking and intrusive. When Elvis’ eyes are opened to what his “friend” and “father figure” truly is, he tries to cut and run. But the Colonel has all the literal receipts to insist that if Elvis really wants out of their contract, he’ll just have to pay the eight million-plus-dollar loan Colonel has “given” him since the beginning of their “partnership” together. And yes, the Colonel received a fifty-percent cut of certain aspects of Elvis’ earnings, obviously unheard of. Yet all Elvis ever really cared about was being himself.

At one moment during a visit to Beale Street for refuge, B.B. King tells Elvis of the Colonel trying to suppress his rebel image, “The Colonel’s a smart man, he must have a reason.” What he means is that the Colonel has some ulterior motive to want to keep the government off their backs regarding Elvis’ “indecency.” What that motive is, Elvis can’t really think about. He’s still too much under the spell of doing what he’s told because his career, so new, is something he doesn’t want to lose. For that would also mean losing his ability to “rescue” his family, which is all he’s ever desired.

The one thing he doesn’t go along with at the beginning is when they tell him not to move so much while recording in the studio. He replies, “I can’t move, I can’t sing,” omitting the “ifs” in his parlance. And yes, his ever-changing intonations are part of what Butler focuses on in his performance, with The Ed Sullivan Show debut being a prime example. One that also happens to provide another Tom Hanks-oriented meta aspect being that Forrest Gump was supposed to have been the one who helped Elvis learn his moves while he was staying in Mrs. Gump’s house.

Although Luhrmann remakes Elvis entirely into a sacrificial lamb without addressing some of his more dubious qualities, maybe the real purpose—apart from showcasing Luhrmannian glamor belied by rot—is that fame actually has come a long way since the “Dark Ages” of the twentieth century. A time when Elvis presciently said during a press conference in 1972, “I think there’s room for everybody [in entertainment].” Of course, he couldn’t have foreseen the over-saturation of “entertainment” on mediums like TikTok and just how significantly such “democratizing” outlets would apply Andy Warhol’s aphorism about everyone having their fifteen minutes of fame in the future.

A kind of fame that has little to do with bona fide talent or showmanship (as Jennifer Aniston recently got in trouble for highlighting). Few people are actually moved by what they do in the arts at this juncture, merely wanting to cash in on virality to avoid labor of the Amazon warehouse variety. Elvis, on the other hand, was forever moved by music. It’s what fueled him to keep going. Which is why the most fitting quote for Luhrmann to conclude the film with is, “I learned very early in life that ‘without a song, the day would never end; without a song, a man ain’t got a friend; without a song, the road would never bend—without a song.’ So I keep singing a song.” And because his legend keeps getting revived, he will until the end of time (sooner than we think). Because, like Michael Jackson (so obsessed with being the new “King” that he married Elvis’ daughter), apparently you can’t cancel Elvis.