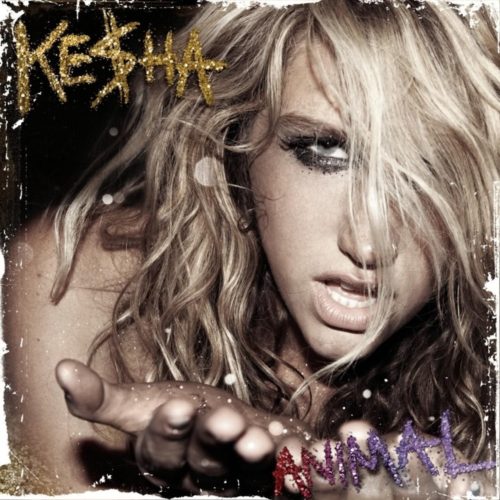

Despite indications of the apocalypse/living in a simulation being manifest at the outset of 2010, Ke$ha decided to ignore those early signs of it by blowing glitter onto all of our faces and telling us to follow her into the night. As in the night of literally day one of January, when Animal was released–for it seemed Ke$ha (as it was styled during the germinal phase of her career) was determined to make the statement: I am here to shape and reflect the narrative of this decade. One that saw millennials come of age into their version of adulthood, or as close as they could come to it in a post-financial crisis world that had run out of resources and much in the way of “plentiful” job options. That said, Ke$ha was the first to openly declare her adeptness at juggling daily responsibility with nightly fun, admitting, “When I leave in the morning I ain’t comin’ back.” Thereby announcing a work ethic for a new kind of generation, one more sloppily unabashed than Don Draper’s slicker, more discreet Silent Generation.

In contrast, millennials and their wasted wench of a pied piper had decided theirs would be a lifestyle filled with frivolous fun if it must still require work obligations. Ones that would be alleviated by a bottle of Jack intermixed with spontaneous sexual encounters (as Ke$ha elucidates on “Blah Blah Blah,” “Meet me in the back with a Jack and the jukebox/Don’t really care where you live at/Just turn around boy, let me hit that”). In every way, Ke$ha was illustrating and sanctioning the behavior of a generation that had nothing left to lose, that simply wanted to party through the world’s assumed end in 2012 (hence Britney Spears’ “Till The World Ends,” which Ke$ha also jumped on the remix for with Nicki Minaj). Little did they know, the end would be a slow burn, best served cold for Gen Z in the next Ice Age, and that they would have to live with the mistakes and random flashbacks of their trash-tastic behavior. Behavior that wouldn’t sit so well with them as they advanced into their thirties (a time in which philosophies such as, “Got a water bottle full of whiskey in my handbag/Get my drunk text on/I’ll regret it in the mornin’/But tonight I don’t give a, I don’t give, I don’t give a” didn’t transfer so well).

And yet, you can’t keep a bona fide millennial down, or away from un certain penchant for puerility. Particularly when a lack of adequate finances prevented many a millennial from ascending into a more classic iteration of adulthood. Ke$ha, too, seemed to refuse to “grow up,” and certainly had her trailblazing fourth-wave feminism moments (a retrospective irony considering her abusive situation with Dr. Luke at the time), citing in the months leading up to Animal’s release, “I think I am really irreverent and I pretty much just talk to and about men the way men talk to and about women. I just think it’s a double standard that unfortunately still exists. Because if I were a man… on pop radio, [I] could say the things I say about men and women and nobody would even think about it twice.” Yes, in many ways Ke$ha revived an aesthetic and persona that favored the long dormant raunchiness of late 70s/early 80s female rock icons like Heart and The Runaways. A reminder to female millennials to take back their power and give in without shame to the temptations of the night.

So it was that with more than a slight daub of glitter, worn like some sort of armor, Ke$ha took on the darkness with the rest of her millennial militia, each one trying to obliterate the notion that wealth was something to aspire to when embracing the sleaze of a low-income paycheck could be so much more fun (Ke$ha even later had a song called “Sleazy”). All they could do was surrender to inherent trashiness (of a purer kind than the 00s Ed Hardy one) in a fledgling economy that made low-budget “personalities” like Kim Kardashian somehow transcend into “stars.” And for those who might at this point say “OK Boomer” to any deference for what Ke$ha did with Animal, let us not forget her own ultimate boomer-shading track, “Dinosaur,” on which she spat, “You are a dinosaur/An O-L-D M-A-N/You’re just an old man/Hitting on me, what?/You need a CAT scan.” Ah yes, a pioneer for anti-old white man “rants” of the 10s if ever there was one (further elaborated on 2019’s “Rich, White, Straight, Men”). As well as flipping the script on the trope of slut-shaming, reversing it to be from the perspective of the woman calling out the man for his philandering behavior with the lyrics, “I never thought that you would be the one/Acting like a slut when I was gone/Maybe you shouldn’t oh oh oh/Kiss and tell.” Calling out men a.k.a. fuckboys for their bad behavior while welcoming her own would serve Ke$ha well over the course of her next few albums (namely the Cannibal EP and Warrior), as well as galvanize all those many acolytes looking for a savior to lead them into a new decade of decadence and debauchery. A feat she seems determined to accomplish again this January of another new decade, poetically bringing Animal full-circle with High Road.

To be sure, whether given credit or not, Ke$ha shattered a glass ceiling not just for herself but other pop stars after her as she thumbed her nose at those who would actually deign to be “scandalized” by her “outrageous” behavior–the very same kind that male musicians have been praised for since the dawn of the modern music industry. And it was Ke$ha who, in the midst of raging through her own anguish (something she couldn’t come to terms with until later on), gave fellow millennials the so-called permission they needed to party through the apocalypse–still, evidently, ongoing.

Did Animal age gracefully? No, probably not (though “Your Love Is My Drug” is still passable). But then, neither have the millennials it resonated with. And that, in truth, is what makes Animal one of the most seminal records of a decade, a genuine time capsule from an era when we were all so braced for it to end, not knowing that “the end” is never a grand bang and fade to blackness but an interminable fizzle out. Like a “party at a rich dude’s house” and the rich dude just wants to keep forcing everyone to do degrading things in exchange for money or drugs so as to keep beating the dead horse that is numbed out, simulative existence.