Erotomania is a subject often addressed in film, though rarely from the female perspective. For the most part, it is male-oriented obsession that drives the plot of a thriller or even rom-com (see: Fear, Love Actually or Say Anything–though not necessarily in that order). But one of the films that set the precedent for the all too common reality of women convincing themselves of a relationship with a man who actually has no interest in her is Alan Shapiro’s (as well as Alicia Silverstone’s) debut feature, The Crush. Released in 1993, at the height of the “erotic” thriller genre’s bankability, the narrative follows Nick Eliot (Cary Elwes) after freshly moving to Seattle for a researching job at a magazine called Pique. His decision to move into the guest house of a mostly absent, high-powered married couple, Cliff (Kurtwood Smith) and Liv Forrester (Gwynyth Walsh), with a precocious only child named Adrian (Silverstone) sets off a chain reaction of dramatic events he could never have anticipated.

Chiefly, of course, it’s Adrian’s swift preoccupation with his comings and goings that gradually–almost too gradually, but hey, that’s the curse of needing to stretch out a three-act structure–begin to make Nick feel uneasy. Initially, he writes off her seemingly dopey girlish crush as nothing more than a transitory fetish. It isn’t until an age appropriate co-worker, Amy (Jennifer Rubin), shows up for a barbecue at Nick’s that he’s forced to look at her “enthusiasm” with new eyes. Erotomania, defined as “a delusion in which a person (typically a woman) believes that another person (typically of higher social status) is in love with them,” punctuates Adrian’s every action, right down to the secret hidden shrine of his pictures and their initials thrown together repeatedly.

As Amy makes her way through the woods in search of “sticks for the marshmallows,” the lurking feeling of being stalked by another presence pervades the screen as she becomes startled by the sight of a beehive. The surprise continues when Adrian appears to “soothe,” “They all sting. Bees won’t bother you unless you bother them. Wasps are different. They’re territorial, and they’re social.” Amy counters, “Social? Like they want to be friends?” Foreshadowingly, Adrian cautions, “Like they attack in groups.” As Adrian’s line of questioning veers toward Nick, it becomes clear to Amy that there’s something “a little off” about the nature of her crush. Particularly when Adrian cuttingly remarks, Oh, don’t worry, Amy. Some guys really like girls with small breasts.” Later, Amy asks Nick point blank, What’s with your friend Adrian?…she gives me the creeps.” Thus she warns Nick to make the parameters of their relationship clear to Adrian before things get out of hand.

Yet that’s already the direction they’ve long ago gone after Adrian lured Nick to a secluded point near the water and somehow finagled a kiss earlier in the narrative. Of course, she later wields this fact against him, skewing it as part of her logic for believing he could truly love her. That she’s also stolen a high in sentimental value photo of him and his grandfather from the outset of him moving in later appears like small potatoes compared to the subsequent wrath she’s about to inflict. Using the combined resources of her intelligence and mask of innocence, Adrian is able to exact revenge upon both Amy–for her attempt at taking Adrian’s so-called place–and Nick. For if she can’t have Nick, then obviously no one else can. Always one step ahead of him, she even manages to con him into watching her undress from the vantage point from her closet, soon after acting complicit in a lie with him after he runs into her father on the way out and corroborates Nick’s story that he was just returning a book (“you must mean Wuthering Heights”). The depth of her conniving, psychotic ways are made all the more powerful by the mask of her chastity and virtue–two qualities she accuses Nick of corrupting when he won’t reciprocate her very overt sexual advances.

With only two people on Nick’s side willing to believe that a “little girl” like Adrian would never be capable of the diabolical things he claims, he is utterly at the mercy of her erotomania–a disease that can only be quashed by transference to another person.

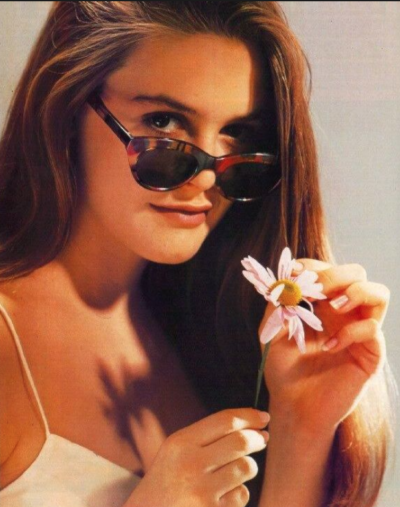

For the most part, 90s films with regard to female delusion pertained to the anti-heroine in question getting overly obsessed with another woman (e.g. Single White Female, Poison Ivy, The Hand That Rocks the Cradle). The Crush, on the other hand, established a new prototype for the cinematic world, presaging the likes of He Loves Me…He Loves Me Not (indeed, the ending to this film is very similar to the one in The Crush), Homecoming, Obsessed, The Bridesmaid, Closer and The Spectator. In the days of Golden Hollywood, the obsessing was always left primarily to the man (with rare exceptions to the rule like Leave Her To Heaven), and usually only because he was out to con her for reasons of financial gain (Sudden Fear, Nights of Cabiria). But Shapiro firmly shattered this previously established norm in a momentous way, creating some sort of reverse Lolita meets Fatal Attraction (Disclosure starring Michael Douglas and Demi Moore the year after would also prove the chain The Crush set in motion). Because that antiquated maxim detailing men as the overly amorous ones in novels like The Sorrows of Young Werther, The Red and the Black and Anna Karenina simply doesn’t hold true. Just look to the petal falling from Adrian’s fingertips as she gives her crush a knowing and appetitive glance for confirmation.