Perhaps it’s the modern equivalent of a “casting couch.” This new trend of being cast on the basis of one’s social media prowess. Between Maya and Ethan Hawke commenting on how someone can now be cast in a movie so long as they have a high number of followers and Miquita Oliver telling Lily Allen (on the February 19th episode of Miss Me?) that the BAFTAs have succumbed to favoring the cult of celebrity (with Kylie Jenner’s appearance as Timothée Chalamet’s date being a contributing factor) over honoring the art of cinema, it’s apparent that a sea change has been happening in the world of film acting. More specifically, the “influencer-ification” of casting.

While it’s already been clear that the downward spiral in filmmaking (not film-generating) has been ongoing since the internet helped furnish “streaming supremacy,” it’s only gotten worse for the acting element of it since 2020, when coronavirus shut down most productions and movie theaters. Taking a hit like that was bad enough, but then came the 2023 Writers Guild and SAG-AFTRA strikes, which shut down productions for most of the year. A hardship that meant, for writers and actors who aren’t at, let’s say, a Julia Roberts level, moneymaking-wise, had to tighten their belts in order to survive during that volatile moment.

And it’s a volatility that’s making those who control the purse strings even less likely to “experiment” with their money by taking a gamble on a person or project that they don’t see as mainstream enough. Therefore, most likely to secure back their investment and then some. Which is why, increasingly, producers are unwilling to consider talent that doesn’t already have a “built-in following.” That includes, of course, nepo babies like Maya Hawke, daughter to Uma Thurman and the abovementioned Ethan Hawke. But even they aren’t immune to the vagaries of KPIs and engagement rates. Case in point, Maya Hawke mentioning on the Happy Sad Confused podcast, “I’ve talked to so many smart directors. I’m talking to them about how I’m going to delete my Instagram, and they’re like, ‘Just so you know, when I’m casting a movie with some producers, they hand me a sheet with the amount of collective followers I have to get of the cast that I cast.” Which means, of course, that not only does an actor (or, as is becoming more common, an influencer-turned-“actor”) have to stress about such an inanity—one that seems particularly inane if they’re in the profession expressly for the art of it—but they also can’t even “disconnect” if they want to.

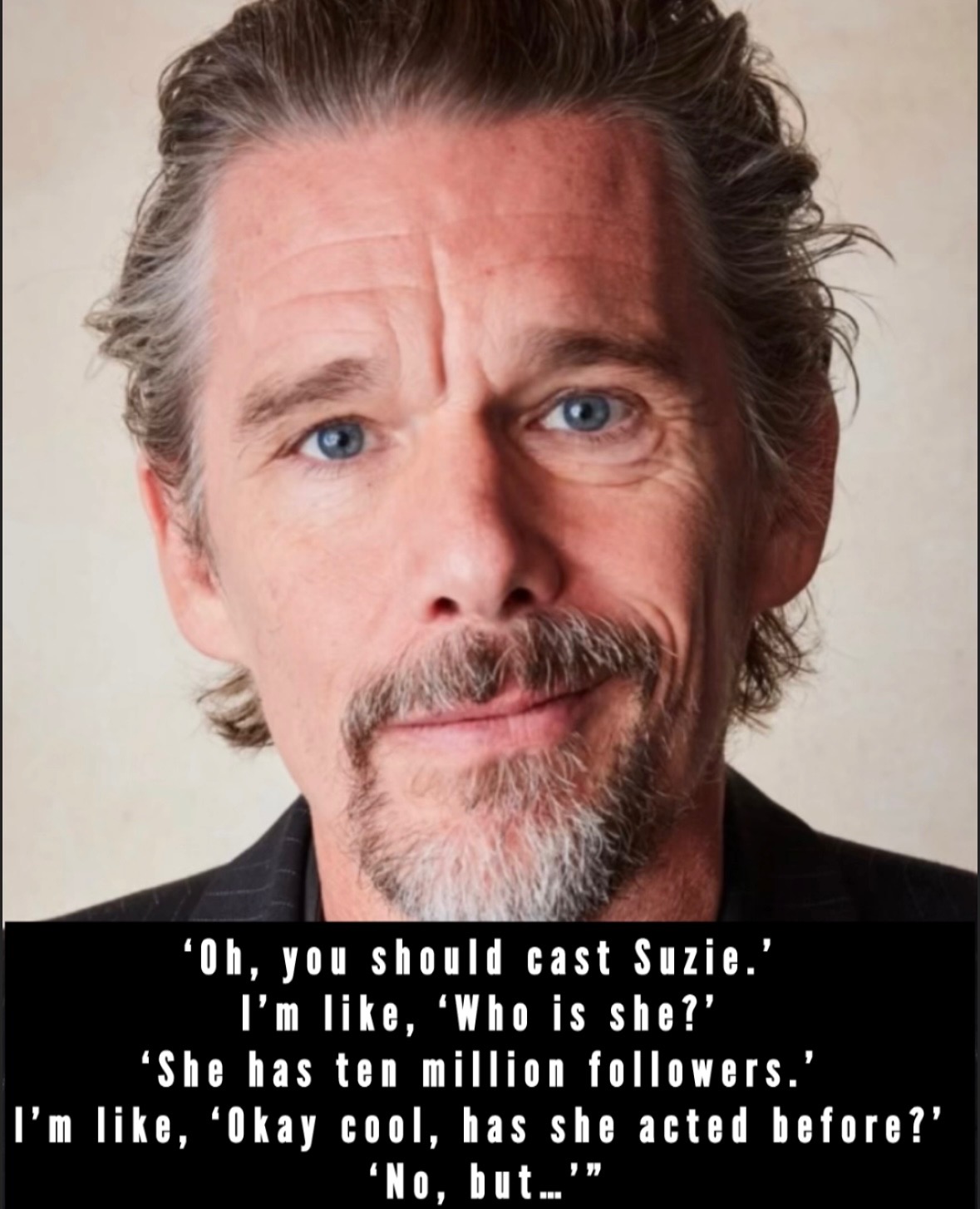

When Ethan Hawke was asked at the Berlin Film Festival (in support of his upcoming movie with Richard Linklater, Blue Moon) about what he thought of his daughter’s comments on the podcast, he replied, “I really feel for these people [a.k.a. the actors who just want to be actors without worrying about a follower count]. It’s really hard. Sometimes I’ll be setting a movie up and someone will say, ‘Oh, you should cast Suzie.’ I’m like, ‘Who is she?’ ‘She has ten million followers.’ I’m like, ‘Okay cool, has she acted before?’ ‘No, but…’ And you’re like, ‘Wow, so this is going to help me get the movie made? This is crazy.’” That’s one word for it. Another is: troubling. Or: horrifying. Along with the normalized phobia of creating any art that might be deemed “offensive.” Because to offend one group or even one person is to lose out on potential revenue. The fear that money (or, more to the point, losing money) has instilled in so many modern creators has come at an even greater cost: the compromise of art.

What’s more, as Hawke also brought up at the Berlin Film Festival, it’s the makers of film that play a key part in essentially sanctioning “being offended.” Ensuring that audiences are just that if they ever see anything that’s even slightly “off the beaten path.” The expected trajectory. Thus, Hawke added, “Audiences have to care. They don’t sell. You guys, the community, has to make it important. For offensive art to have a place in our conversation, it has to be cared about. And when we prioritize money at all costs, what we get is generic material that appeals to the most amount of people and we’re told that’s the best. It’s a dance we all do together. If you love offensive art and you want it, demand it. Right now, people don’t think they’ll make any money off it, so it doesn’t get made.”

It seems less and less likely that any such work ever will. Even in the realm of independent cinema, which has become increasingly “blockbuster” since the days when the Independent Spirit Awards first began in 1984. That Sean Baker should also feel obliged to speak on the state of “the business” during his big win at this year’s ceremony serves as an additional testament to how bad it’s gotten if even indie filmmakers have to concern themselves with how many followers their lead actors have. Hence, Baker’s shade-throwing comment, “We want complete artistic freedom and the freedom to cast who is right for the role, not who [we’re] forced to cast [when] considering box office value or how many followers they have on social media…”

So, clearly, this is becoming more and more of an issue. That is, artists’ input being trampled on by the suits when it comes to artists’ work. Alas, because of that odious adage, “He who controls the purse strings makes the decisions,” no one on the creative side of filmmaking is immune to the dictums of producers. Which, presently, insists upon leaning into the whole “influencer” phenomenon. Even if, with the Orange One’s recent temporary TikTok ban, people have been made aware how fragile that kind of “career” is. And if there ever is a Leave the World Behind-type scenario (i.e., a new Dark Age wherein the internet, de facto social media, “goes out”), well, an internet following isn’t going to mean much.

Hence, Ethan Hawke incredulously demanding, “So if I don’t have this public-facing [platform], I don’t have a career? And if I get more followers I might get that part?… What?” Further adding, “So many young actors that think being an actor is protein shakes and going to the gym…go to the gym if you want to, but that doesn’t make you [an actor]… Robert De Niro is not great because he has a six-pack. If the part calls for it, he’ll do it, and that’s awesome, but he’s so much more than that.” Certainly more than his followers—which don’t really exist as he’s not on social media (a choice that worked in his favor amid that gender discrimination lawsuit). But then, he didn’t come up during a time when every creative person was indoctrinated with the belief that they “need” to have social media. Not just as a means to “showcase their talent,” but to ensure they’ll even be considered by a “higher power” at all.