Considering that screenwriter Ebbe Roe Smith himself was born in Southern California, he knew all too well the ripple effect that transpired when the aerospace and defense companies left town. The ones that had surged in the post-war boom so much that it entailed the building of what can best be described as “artificial communities” throughout Southern California. Places that didn’t really exist until a slew of cookie cutter houses were plopped down into a cul-de-sac. No one seemed to mind the ersatz feeling–this manufactured life to mirror a manufactured class. But what happens when the buttresses for that manufactured class–companies like Lockheed, Raytheon and Boeing–decide they’d rather take their business elsewhere? More to the point, to a city and state with more political and financial incentive. In the early 90s, the migration of Raytheon and Lockheed out of Southern California made massive dents in the economy of Los Angeles County that, for whatever reason, people (read: blancos) would have preferred to pin on the seismic shift that seemed to be timed right after the Rodney King riots.

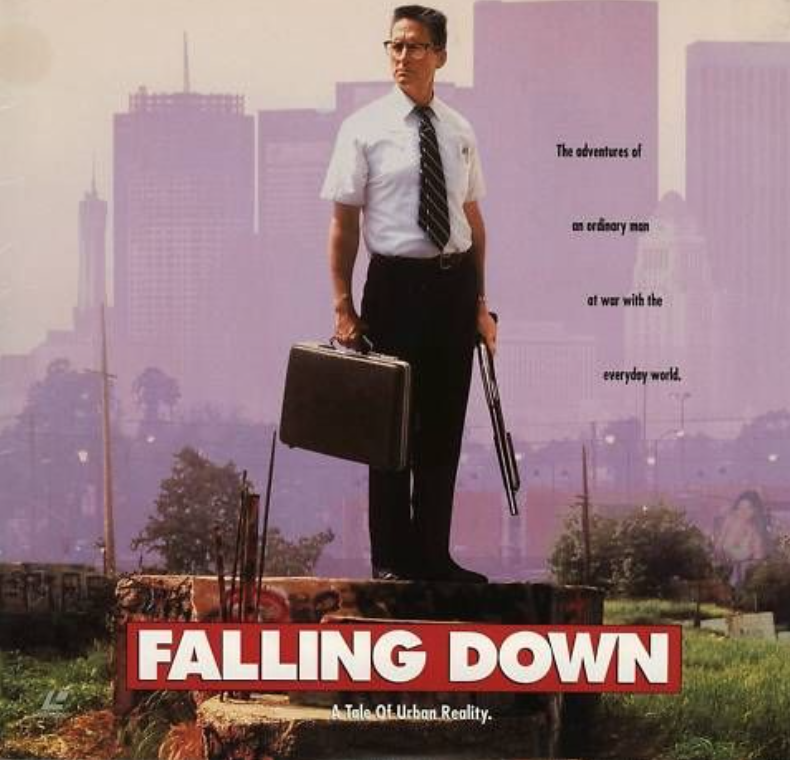

Maybe even people like William “D-FENS” Foster (Michael Douglas), the prototypical irrelevant white male, would have preferred to place the blame on an event so recent and palpable. But the truth of the matter was, a sea change in the city (and the country it reflected) had been brewing for years. A collective and conscious decision on the parts of the very companies that shaped the landscape to rip the cushion of “luxury” out from underneath the middle and working class–and, with it, the veneer that once shielded how only two classes ever remain: the congenitally rich and everyone else. To compound matters for Bill, however, he’s faced with the stark realization that being a white middle-aged male no longer bears any standalone power either. Stripped of his livelihood and the clout of his color and gender that he once thought was immutable, Bill is tipped over the edge the moment we’re introduced to him sitting in his mediocre car, saddled with a less than mediocre life. As his eyes scan his oppressive surroundings, a bumper sticker advertising a number to call for “Financial Freedom” is just one of many entities (along with a grinning Garfield attached to the inside of a window) that seem to mock Bill as he suffocates and sweats in his vehicle–all in a scene highly reminiscent of the opening traffic jam in Fellini’s 8 ½.

Unable to withstand the heat literally or metaphorically for another second, Bill exits his car and walks off the freeway, announcing to the angered man behind him that he’s going home. A police sergeant named Martin Prendergast (Robert Duvall) happens to insert himself into the drama when a highway patrolman is called to the scene to invoke a tow truck. Prendergast insists they instead move the car to the side of the road, intervening despite the fact that it’s his last day on the job, something he tells the patrolman only after he’s gotten him to agree to his will. Call it the innate intuition of that rare thing–being a good detective–but Prendergast gets the sense that towing the vehicle will somehow cause more harm to whoever abandoned it. It is also his first kismet intertwinement with Bill, whose subsequent activities will sound major alarm bells in Prendergast’s worried gut feeling throughout the rest of the day.

Bill’s acts of rage, of course, start out minimally enough, spurred first by a Korean convenience store owner who sets him off by over-charging for a can of Coke when Bill only buys it to get fifty cents change for the pay phone after being hung up on by his ex-wife, Beth (Barbara Hershey). Vexed not only by this form of very literal highway robbery, but also the owner’s accent, Bill finally berates him when he demands, “Eighty-fie sen.” He returns, “What? I don’t understand ‘fie’–there’s a ‘v’ in the word five. No ‘v’s’ in China?” The owner corrects, “Not Chinese. I’m Korean.” Bill shrugs, “Whatever. You come to my country, take my money and don’t even learn my language?” This age-old tension about “true assimilation” (an argument made since the dawn of boatloads of immigrants rolling up to both Angel and Ellis Islands) had been re-stoked during this era precisely because of the reason it always comes up: job scarcity. The feeling that said scarcity is only further worsened by the presence of “immigrants” a.k.a. “the other,” “the infector,” “the root cause of the problem.” The easy scapegoat, especially for increasingly anachronistic white men who never had to think about where (or how) they fit into the world until recently when “women and minorities started asking for too much.”

At the same time, Bill’s dichotomous persona shines through in moments when he relates to the black man outside of a bank with a protest sign that reads “Not Economically Viable.” His empathy for this man intensifies as he’s arrested by police and the man shouts out the window at him, “Don’t forget about me!” Bill assures, “I won’t.” How can he? He is him. Two men with no worth in society’s eyes because their ability to make money has been stripped from them, setting off the spiral of “falling down”–on the economic ladder, that is, and, consequently, the mental one. His contrary nature is highlighted again when a white supremacist at an army surplus store protects him from being discovered by Prendergast’s co-worker, Sandra Torres (Rachel Ticotin). Having heard about him on the police radio he listens in on after Bill shoots up a Whammyburger for not giving him a product that mirrors what’s advertised in the image, Whitey assumes Bill is “like him,” explaining as he hides him in his bunker filled with Nazi paraphernalia, “I’m with you, don’t you get it? I heard about the Whammyburger. Fucking fantastic! It’s a bunch of niggers, right? On TV, it’s always white kids, but you go in there, it’s nothing but a bunch of niggers. They’ll spit on your food if you’re not nice. I know all about it. I’m with you. We’re the same you and me, don’t you see?” But Bill doesn’t see.

He doesn’t view himself as racist or chauvinist or even entitled. To him, something has simply happened to the “great America” he used to know. One where considerations for others outside of the white male bubble of “supremacy” were never necessary. Yet it was during this so-called “Golden Age” of American life that the ugliness of society was ugliest of all because of sweeping under the rug the realities of those who really suffered to fortify the illusion of “the American dream.” So it is that this fear of losing all semblance of “dominance” and “preeminence” materializes in these hostile, “cry for help” ways of white men–seeming always, in the end, to result in the use of gunfire.

As the lengths of Bill’s rampage escalate, director Joel Schumacher, despite being born in New York City, captures the essence of Los Angeles during this period as few others could. Who knows? Perhaps the fact that one of his earliest gigs in film was working as a costume designer on Play It As It Lays seeped in permanently, based on his ability to evince the sweeping immensity of L.A., yet, at the same time, its intense microcosmic claustrophobia (particularly compounded whilst in traffic).

What neither Schumacher nor Smith could have predicted was that their unwittingly cautionary tale toward government institutions and major corporations in control of the fate of people’s livelihoods would go unnoticed and unheeded. For it’s clear that what we still haven’t seemed to learn is that regardless of your background or race, the branding of being “not economically viable” makes everyone susceptible to Bill’s fate of being “put out to pasture.” For you are useless to society if you cannot contribute to the machine of its taxes or other moneymaking interests. Yet such a notion gets caught in the vicious cycle of the government’s and The Corporation’s callous neglect, investing in their own profits rather than people. People who are mere numbers to them as supposed to someone to be nurtured and supported, even if it involves repurposing their role by training them in a new skill. Alas, in this world, particularly the United States, what purpose do you have if not to make money, therefore work at a job that likely has nothing to do with something you might actually be passionate about?

Furthermore, Falling Down taught us not to regard the rantings and mood swings of white men as something to mock or write off, for, it turns out, we still have to cater to their delicate sensibilities if we want to keep them from destroying the world, one melodramatic outburst at a time. The obvious incidence of this being the current sitting president, an ultimate beacon of toxic white (as orange) male culture mutated into something even more horrendous than we ever thought it could be back in the 90s. With Bill as something of a blueprint for the incel turned irate because he can’t “get what he wants” (usually sex) how or when he wants it, we see that this genesis kept progressing to the mutant point it’s at now (also elucidated by Joaquin Phoenix’s rendering of the eponymous character in 2019’s Joker). Along the way, a new benchmark for the anger of white males over their feelings of being “anachronistic” in a society that suddenly “favored” fags, nigs and sluts (what all women are, n’est-ce pas?) manifested in the form of the Columbine shootings.

At the same time, the “victimhood” of the white male is a myth perpetuated by representations like Falling Down. After all, there’s something to be said for the fact that it is still the privilege of the white male to have a “full-on Britney” meltdown (for even Britney could not have hers without it tainting the rest of her career by becoming an easy target for mockery), or even a Kanye-inspired one. Ergo, the Orange One running absolutely rampant and unchecked in his “eyes bugged out” level of psychotic mania.

Ultimately, what we still haven’t learned is that we remain perpetually subjected to the fallout–the accruing shrapnel–of the white male tantrum, whatever violent turn it might whimsically veer toward next. Apparently, it’s somehow still all of our jobs to teach him to accept that there are “others” on this Earth, and that privilege and outrage do not belong to him alone. Yet because of this–his trapped in the past mode of thinking–it’s ashes, ashes, we all fall down.