From the frenetic, moody opening that is “I Want You to Love Me,” it’s clear that Fiona Apple is experiencing the same rat in a cage tendencies we all are at the moment. Of course, she couldn’t have known that during the eight years she spent making the record while in her Los Angeles home (like all sensible New Yorkers, she fled to the West). That her last record, The Idler Wheel…, was released in what was supposed to be the apocalyptic year of 2012 feels pointed. For now here we are in what seems like a far more tangible taste of apocalypse. Even if it is a slow burning rather than a crash and bang one. Perhaps something in Apple sensed the sea change afoot, or maybe it’s just another instance of happy circumstance in pop culture–for every track speaks to a certain form of imprisonment, paired with an insatiable desire to break free.

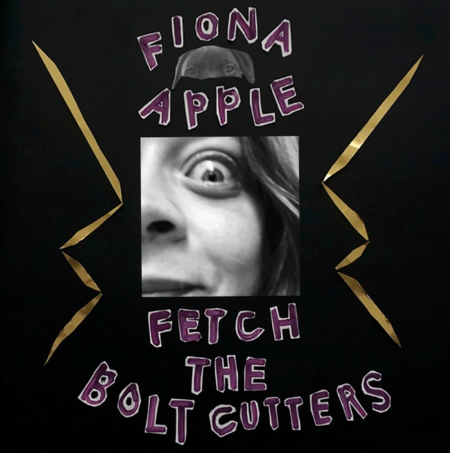

A title like Fetch the Bolt Cutters is also, of course, all too apropos, and stems from the British-Irish crime series, The Fall–the words taken from the mouth of main character Stella Gibson (Gillian Anderson). That Apple should take inspiration in naming her album from what has been heralded as one of the most feminist TV shows to date is telling of where head is at–and has been since we were first introduced to her in the 90s. Self-produced and unapologetically raw in its sound, the record is centered around a theme of not being silenced–something women remain all too versed in despite the “advancement” of society. And yes, Apple does well to bring up more “analog” issues in a news cycle that has been inundated with nothing but coronavirus doom and gloom. But beneath all that, we must not forget about the injustices that have not gone away (with COVID-19, in so many regards, still serving to highlight these disparities). The rawness of it all even extends to the cover art, showcasing a faint glimpse of half of Apple’s face staring madly into the camera, as though she’s parodying a profile photo for earlier iterations of social media (right, that basically means MySpace). A coloring book-like font for “Fetch the Bolt Cutters” further accents the “messiness” of it all. But it is a precise messiness–for that has always been the genius of Apple: a controlled chaos. One can consistently tell she’s the total owner of her tumult. The disarray is part of her therapeutic process. Just as one pictures it to be in homes throughout the world right now as people rage and rebel in their own quiet ways as a means to cope.

The method of her creation–in near total isolation (as all great artists must create)–is manifest in the lyrical content, even something as seemingly love song-ish as “I Want You to Love Me.” As a piece she worked on over a period of years, Apple has stated that it became about different people at different times (including on again, off again boyfriend Jonathan Ames). Yet, ultimately, it became about, “the nature of things. That whole thing of, ‘If a tree falls in the forest and no one’s around to hear it, does it make a sound?’” By Apple’s estimation, “Yes, it does. Because a vibration happens. Whether or not you’re there to hear it. I exist whether or not you see me. These things about me are true whether or not you acknowledge them.” As someone who was raped at twelve and likely had to live with the “did that really happen to me?” weight of something so egregious, Apple knows all about keeping something to oneself and the awareness that just because no one knows about it (at least not right away) doesn’t mean it didn’t happen. Doesn’t mean it won’t affect and damage–again this can be extended to the quarantine metaphor: just because we aren’t seeing other people gradually unravel in isolation does not imply they aren’t. The poetical and the divine are present in the lyrics, “I move with the trees in the breeze/I know that time is elastic/And I know when I go/All my particles disband and disperse/And I’ll be back in the pulse/And I know none of this will matter in the long run.” These are wise words to disseminate to the masses (or at least the few with musical taste) at a moment like this where everything appears quite literally grave.

Maybe that’s why Apple chooses to lend a bit of levity with “Shameika,” a ruminative-on-the-past track that explores the origins of what Apple calls her “fucked up” relationship to women. For she never fit in with the popular, stick up their ass girls, making school feel all the more like a quarantine-esque prison as she sings, “In class, I passed the time/Drawing a slash for every time/The second hand went by a group of/Five, ten, twelve times is a minute.” The broad elasticity of time, indeed, seems to run heavily throughout. With Shameika, the requisite tough girl in school, assuring Apple that, somewhere down the line, she would be vindicated, not needing to settle for basics who didn’t want to be her true friend anyway. As the type of character in one’s life who only makes a brief cameo to deliver a life-altering revelation, Apple explains, “Shameika wasn’t gentle and she wasn’t my friend but/She got through to me and I’ll never see her again.” In the small span of a song, Apple conjures easy images of her little white girl existence in Harlem at a time when being white there wasn’t the expected norm of gentrification. She also references this period in her life by mentioning 1985’s Hurricane Gloria (New York’s then first major hurricane since 1960). And so, the deftness of Apple’s songwriting style is again underscored with each track on this record.

This, too, goes for “Fetch the Bolt Cutters,” one of the most defiant songs on the eponymous album. In many ways an echo of Lana Del Rey’s “High By the Beach” or Bobby Brown’s/Britney Spears’ “My Prerogative,” this is Apple’s staunch anti-media anthem. The one that declares she is no longer hemmed in by so-called public or critical opinion, a phenomenon she fell prey to at the outset of her career. So it is that she urges us all to “fetch the fucking bolt cutters and get yourself out of the situation that you’re in—whatever it is that you don’t like.” And no, Apple did not like being in the situation of media scrutiny and dissection. Ergo, the entire track feels like a direct address toward the collective entity as she fights back, “I’ve been thinking about when I was trying to be your friend I/thought it was then, but it wasn’t, it wasn’t genuine/I was just so furious but I couldn’t show you/’Cause I know you and I know what you can do/And I don’t wanna war with you, I won’t afford it/You get sore even when you win.” Effectively laying into the no-win situation any young female musician has in a dynamic with the press, Apple perhaps lights the way for other women not to make the same mistake in the beginnings of their spotlit journey.

This unabashed defiance persists on “Under the Table,” a title with an ironic duality, for we think of things hidden as being relegated to under the table, yet here Apple declares she will chase all such concealments out with, “Kick me under the table all you want/I won’t shut up, I won’t shut up.” Inspired by an actual bourgeois/social climbing dinner she was forced to attend, Apple’s contempt for certain guests is all over the song in isms like, “I would beg to disagree/But begging disagrees with me” and “I’d like to buy you a pair of pillow-soled hiking boots/To help you with your climb/Or rather, to help the bodies that you step over along your route/So they won’t hurt like mine.” Savage to the bitter end Apple is. And that’s what makes her brilliant. There is no “softening with age,” only a further realization that it was always as she said, “This world is bullshit.”

An endless relay of bullshit, to be sure. Which is precisely what “Relay” addresses as Apple talks about the vicious cycle of evil that gets perpetuated when an abuser turns his victim into the same. Inspired by a combination of her assault when she was barely a teenager and the feelings of that violation being rekindled by Brett Kavanaugh’s appointment to the Supreme Court, Apple insists in the end, “I know if I hate you for hating me/I will have entered the endless race.” A very Kabbalist perspective indeed. Yet the fifteen-year-old Apple who came up with the line, “Evil is a relay sport when the one who’s burnt turns to pass the torch,” was still enraged enough to reemerge in 42-year-old Apple when she finished the song. For, like the rest of us, she has been vexed to no end by Kavanaugh and his ilk’s genuine belief in their own innocence as she noted to Vulture, “The Kavanaugh hearings in 2018 brought on a lot of shit to deal with. I don’t know what it is, that guy. There are so many of them out there, but that one guy—the fact that he’s on the Supreme Court really is probably the thing, but his fucking attitude is just like—it was the externalized version of what you know a lot of them are feeling inside. Just this indignant, ‘How could you be mad at me? Don’t make me suffer. But I’m married, but I have kids, so I can’t be a bad guy. But I was just young, don’t be so mean to me, that girl’s being mean to me.’ Oh my God. Thank you, fucking Brett Kavanaugh, for letting my anger see the light of day: Thank you for being so horrible.” It is that anger that reaches a wondrous and resonant crescendo in the lines, “I resent you for being raised right/I resent you for being tall/I resent you for never getting any opposition at all/I resent you for having each other/I resent you for being so sure/I resent you presenting your life like a fucking propaganda brochure.” An undoubted allusion to the social media “influencer” cluster fuck, this propaganda brochure is, of course, increasingly difficult for people to feign in quarantine.

Even celebrities are running out of rooms in their house to post in. Regardless of whether the rooms are filled with racks of guitars for added aesthetic show. That very image being where “Rack of His” was spawned, transforming into, in Apple’s wordplay aptness, a flipped script on objectification. Discussing her devotion in a relationship (again, knowing Apple, it refers to an amalgam of them), the descriptions come across as ennui-laden homages to being stuck in a toxic dynamic. Phrases such as, “I followed you from room to room with no attention/And it wasn’t because I was bored” and “That’s it, there’s a kick and you’ve given up/’Cause you know you won’t like it when there’s nothing to do” subliminally speak to the ways in which couples in the quarantined now are learning that, at the core of their “love” for one another, there isn’t really much to sustain it without the distractions of the outside world.

“Newspaper” opens with yet another round of ambient barking sounds (for Apple’s dogs in her self-isolated workspace are as much a part of the rawness of the record as anything else). With this canine contribution, Apple taps into another very “finger on the pulse” approach in her homemade musical stylings–for everything of late seems to bear this level of grit (Charli XCX, too, is in the process of making a “bare bones” record while also holed up in L.A.) as musicians and normals alike use only the crude tools they have available to them. Again harkening back to Apple’s self-admitted complicated rapport with other women–the competitive spirit of patriarchal conditioning being hard for most of us to stamp out–“Newspaper” unfolds a bizarre love triangle. Seeing a similar fate about to happen to a friend as it did to her with regard to the same man’s treatment, she seems to be speaking to both of them as she accuses, “You’re wearing time like a flowery crown/Sitting there, sitting that big cat down/And I’m alone on the summit now/Trying not to let my light go out.” Once more the queen of powerful, evocative imagery, Apple also laments the need for an unbiased witness in romantic relationships to rehash to others how it all really went down. In this instance, however, it sounds as though she needs the witness for both herself and her female friend as she rues, “It’s a shame because you and I didn’t get a witness/We’re the only ones who know/We were cursed the moment that he kissed us/From then on, it was his big show.” And yes, it is always his big show–whether we’re talking a bloated politician’s or coronaV’s.

To that end, the anthemic “Ladies” is a mutinous track against the patriarchy’s penchant for turning women against each other. As Apple noted, “This album is a lot of not letting men pit us against each other or keep us separate from each other so they can control the message.” The message Apple, instead, would like to impart is, “Nobody can replace anybody else/So it would be a shame to make it a competition/And no love is like any other love/So it would be insane to make a comparison with you.” For to do that is not only ultimately inane, but just another way to feed the depression monster. A monster that’s come out for many in this period of self-sequestering. And it’s a “Heavy Balloon” to bear, if you will. The analogy Apple so eloquently makes on the track of the same name as she sings in solidarity with the clinically crestfallen, “People like us, we play with a heavy balloon/We keep it up to keep the Devil at bay but it always falls way too soon.” That the rhythm has a certain clipped upbeatness is in keeping with Apple’s sardonic sense of humor: the ultimate armor and coping mechanism for the despondent. Her succinct description of how all that should be a source of “joy” when one is in the bell jar becomes only another source of agony puts Elizabeth Wurtzel to shame as she sings, “In the middle of the day, it’s like the sun/But the Saharan one, staring me down/Forcing all forms of life inside of me to retreat underground/It grows relentless like the teeth of a rat/It’s just got to keep on gnawing at me/And it constricts like a boa on a hose, nothing flows.”

She preaches more unbridled truth on “Cosmonauts,” a song originally intended for Judd Apatow’s This Is 40 (instead “Dull Tool” would be used). The song never materialized on the soundtrack because Apple, naturally, had difficulty in catering to the notion of two people being together “forever.” That difficulty in believing has been made all the more apparent in quarantine, with the divorce rate spiking despite the fact that there’s nowhere else to run to in this period of non-functioning lockdown. But still, couples who can’t ignore despising one another would like to at least have the knowledge that when it’s all “over,” they can flee. Alas, before that glorious moment, Apple illuminates that “oh fuck” awareness between couples recognizing they’re trapped with one another as she croons, “Now let me see, it’s you and me, forgive good God/How do you suppose that we’ll survive? Come on, that’s right, left, right/Make lighter of all the heavier/’Cause you and I will be like a couple of cosmonauts/Except with way more gravity than when we started off.”

The inimitable and affecting “For Her”–named as such for the specific woman Apple is referring to and the general abuse many women suffer in silence–features a gospel sound and twang. The deliberateness of this style cannot be ignored, for there is more than a tinge of the survivor tone present in the slavery songs that would go on to mutate in the milieu of Baptist churches. But Apple wants more than just the “badge” of surviving for herself and the women she knows (and doesn’t). She wants the abuser himself to know what he’s done. Really know. Like “Relay,” the song was spurred by the Brett Kavanaugh saga that unfolded in 2018. Only for him to be appointed to the Supreme Court regardless of what these women said. Regardless of a pattern of behavior that suggested Kavanaugh would take what he wanted whether there was consent or not. Based on a woman who started as an intern for a certain Hollywood asshole in the film industry, Apple wields the metaphor of a blow job to perfection with the lyric, “She’s tired of planting her knees on the cold, hard floor of facts/Trying to act like the other girl acts.” Here Apple posits that perhaps if all of us, collectively as women, stopped playing to the “expectations,” men would be the one on their knees in no time. It is at the end of the song that Apple delivers her coup de grâce with the jarring lines, “Well, good morning/Good morning/You raped me in the same bed your daughter was born in/(Like you know, you should know, but you don’t know).” Vicious in a way that few have dared to be, Apple touches on this idea that even men with daughters have the gall–the sheer lack of a moral compass–to rape another girl who is someone else’s daughter. And how would he feel if another man did the same to his own? Anything at all? Or would he pretend his daughter had “over exaggerated” the whole thing? If it’s Kavanaugh we’re talking, definitely the latter.

The album draws to a close with the interlude-like “Drumset,” an elegy for her relationship demise with Jonathan Ames juxtaposed against a misinterpreted slight from one of her band members who took away a drumset to use for another gig. Apple, in her fragile state, assumed that this was yet another rejection; that the band found her somehow too difficult and didn’t want to work it out with her the same way Ames didn’t. To the latter’s regard, Apple berates, “Now I understand, you’re a human/And you got to lie, you’re a man/And you got to get what you want how you want it, but so do I/And I wanted to try.” In the end, of course, it never matters what the woman wants (even when she’s the Queen of England). Though she can certainly put up a good fight about it before the final result is enforced. An unbelievable severing with the reality she thought she knew as jolting as a stay-at-home order.

An order that has the vast majority rethinking their priorities as they struggle to recognize that the bulk of their life was mindlessly running on a hamster wheel, aimlessly seeking some kind of validation (whether verbal, monetary or in the form of some bullshit award) at every turn. This was the case for the common man as much as it was for the artistic genius that is Apple, who has decided: no more. Unwittingly ending Fetch the Bolt Cutters with a mantra for how we live now, she chants, “On I go, not toward or away/Up until now it was day, next day/Up until now in a rush to prove/But now I only move to move.” Or rather, go to the grocery store.

I’m not convinced Hurricane Gloria is referring to Hurricane Gloria. IMO she’s acknowledging Patti Smith’s song from Horses: Gloria – official title “Gloria (Part I: “In Excelsis Deo”; Part II: “Gloria (Version)”