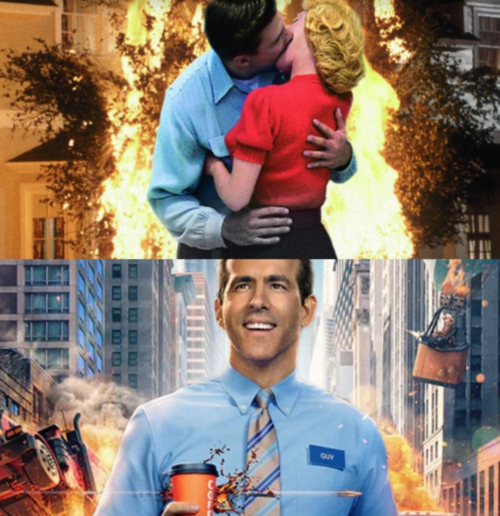

For a movie that could have theoretically been just another “blip” of the 90s, Pleasantville has clearly been on some people’s minds of late. First, there was WandaVision, and now, whether “intentional” or not (because not everything is when it comes to the osmosis of grinding out ultimately repackaged story ideas), Free Guy. Starring everyone’s favorite would-be husband based on how he treats Blake Lively on social media, Ryan Reynolds plays the eponymous Guy. A “man” who is totally unaware that he’s nothing more than an NPC (non-player character) in a massively multiplayer online game called Free City.

That’s certainly a time period-oriented upgrade from being a character in a TV show—the crux of Pleasantville’s premise apart from a grand allegory for what happens when people eat from the proverbial Tree of Knowledge (and yes, there is an apple-eating scene in the movie). The same knowledge that Guy comes to understand as he achieves “self-awareness” thanks to a lingering AI code from Free City’s original creators, Millie (Jodie Comer) and Keys (Joe Keery). And yet, unlike Guy, when the characters in Pleasantville are “awakened,” it isn’t to the idea that they’re just characters in someone else’s narrative, it’s to the prospect of everything that’s been censored out of their existence up to now. Made literally black and white. With the arrival of David (Tobey Maguire) and Jennifer (Reese Witherspoon)—thrust into the show by a remote control given to them by a “TV repairman” (meta-ly played by Don Knotts)—as Bud and Mary Sue Parker, the son and daughter of Betty (Joan Allen) and George (William H. Macy), it is initially Jennifer who goes rogue about introducing things into the town’s sanitized life that they “shouldn’t” know about.

With Pleasantville opening on the channels changing through various TV networks, “TV Time” is very clearly supposed to be the movie’s answer to Nick at Nite. Offering a twenty-four marathon of Pleasantville that’s “chock full of family values,” Bud’s obsession with the show seems to stem more from wanting to live in that wholesome, carefree existence in such direct contrast to his own life and the epoch he exists in. The narrator advertising the marathon urges, “Flashback to kinder, gentler times.” Of course, that’s the great fallacy of “the past,” hence a preference for the totally utopian world of video games in the present—filled with their own (violent) problems as they might be. And as people once disappeared into the television set, so, too, do they now disappear into their “VGs.”

It’s easy to see why David is so eager to retreat into his marathon, what with a man at school giving a presentation on the bleakness of the job market by the time his class graduates and another teacher saying things like, “The chance of contracting HIV from a non-monogamous lifestyle will climb to 1 in 150.” In another scene, a teacher talks about climate change in what now feels like an even eerier forecast.

In contrast, when Jennifer attends a “geography” class once she and her brother have been sucked into the TV, all the teacher can impart is the difference between Elm Street and Main Street. This prompts Jennifer as Mary Sue to ask casually, “What’s outside of Pleasantville?” The whole class turns around and looks at her like she’s a commie. She persists, “Like what’s at the end of Main Street?” The teacher replies, “Mary Sue! You should know the answer to that. The end of Main Street is just the beginning again.”

This close-mindedness to any notion of something “bigger” existing outside of their own small world is also omnipresent in Free Guy, which highlights the idea of free will as well. And while Free Guy’s soundtrack is slightly more limited, the repeated use of Mariah Carey’s “Fantasy” iterates how they’re all living in one. And perhaps that’s part of why Guy is so attuned to the song, being already latently aware of some utopian ideal of people being able to do whatever they want with their time. A phenomenon, incidentally, that still doesn’t occur in real life.

As for Bill Johnson (Jeff Daniels), the owner of the soda shop where David now works as Bud, he would love to do what he actually wants with his time—for he quite literally goes through the same motions (specifically wiping) and doesn’t know what to do if one element of his schedule is thrown off, like when Bud shows up late so he doesn’t feel like he can stop wiping down the counters and start making the fries. This “preprogrammed” roteness in the characters of Pleasantville are less easily “deprogrammable” because they’re human. Whereas the beings in Free City are just codes and algorithms. Granted, Millie and Keys designed their original game, Life Itself, to consist of complex characters with the ability to possess the sort of emotions that come with self-awareness.

And yet, the treatment of Guy and his fellow NPCs is tantamount to David running down the street and shouting, “He doesn’t exist! You can’t do this to someone who doesn’t exist!” as Jennifer goes to Lovers’ Lane with Skip Martin (Paul Walker) with the intent to open his eyes to what sex is. The same might comment could be made of Guy—and yet, to Millie, who has fallen in love with him, he very much exists. That’s the thing about the “unreal”—it often feels the realest.

The one aspect of “awareness” Pleasantville never bothers delving into is how becoming such means being forced to address various class discrepancies. Case in point, Guy asking Millie, “How do I get to a higher level?” She wastes no time telling him, “Experience, guns, money.” Then come the classist implications of a man who suddenly manages to climb above his “station” despite the rigged game very clearly “banning” any such act—just as it is mostly the case in real life.

His co-worker, a security officer named Buddy (Lil Rel Howery), is one of many who are scandalized by Guy trying to interrupt “the flow.” When Guy tells him he’s been figuring things out, the friend snaps, “It is nothing to figure out. You go to bed, you wake up, you get some coffee, then you come to work—and then you repeat the same thing tomorrow.” Come to think of it, yes, that does sound like life for most people. But Guy counters, just as David eventually does to the Pleasantville universe, “What if I could tell you that you could be more? Your life could be fuller. That you’re free to make your own decisions—your own choices!” Well, absolutely nobody wants that, as life on this Earth has made apparent without the parallel of video games.

A sign that reads, “Big sale, always tomorrow!” says it all in terms of the day-to-day monotony that NPCs are expected to endure. Like the characters of Pleasantville, they are designed—just as humans in the modern world—to anticipate an endless barrage of sameness. Reliable “routine” (a form of slavery) that keeps capitalism bolstered and the masses complacent. But Guy no longer wants to live that way. When Millie questions, “Why are you doing all of this?” Guy replies, “I guess I felt trapped…in my life. I just felt so—” “Stuck,” Millie finishes for him. This is true of most of Pleasantville’s inhabitants, including Betty, whose infamous masturbation scene turns everything in the bathroom to color before setting a tree on fire outside. And no, Pleasantville had never had a fire before that instant. Nor any other “unpleasant” natural phenomena, like rain—which David and Jennifer additionally bring with them.

Almost speaking in the exact same style of David during the courtroom scene, Guy declares to Buddy, “Life doesn’t have to be something that just happens to us.” He then tries to present Buddy with a pair of glasses usually reserved for high-level players and tells him, “Just put the glasses on and you’re gonna see.” Here, too, we have a different parallel to another cult classic, They Live, during the infamous scene when Nada (Roddy Piper) tries to get his only friend and ally (who also happens to be Black like Guy’s bestie), Frank (Keith David), to see reality…which, of course, he fights practically to the death not to see, just like most. As Guy attempts to thrust a new world order into Buddy’s face, he can only say, “I can’t.” It actually seems physically impossible to him. To compute a world in which there is choice instead of a preordained “plan” is literally more to bear than staying in the dark.

Even Guy has to admit some form of regret when he finds out the full extent of the truth, asking Millie toward the end of the movie, “So the entire world is a game?” She confirms, “Yes.” Guy, still willing to accept this version of the truth, further demands, “And we’re all just players in the game?” Millie negates, “Not exactly.” The revelation that he and his NPC brethren are not real at all leads him to start berating the characters who keep saying and doing the same things every day, as he barrels through the streets screaming, “None of this matters! None of it! It’s fake! We don’t matter!” Funnily enough, someone should probably run through the streets screaming that in most places.

Elements of another 90s movie, The Truman Show, also come into play when Guy runs to the ocean—the edge of the fake Earth, as it were—and pierces his hand through the dimension during the moments when Free City begins to collapse on itself thanks to Antwan (Taika Waititi), the video game company’s CEO, wiping Soonami’s servers and then smashing them to prevent Millie and Keys from coming up with any evidence that he stole their code.

And yet, just as the black and white ilk—the ones who refuse to turn to color—of Pleasantville try to keep things “status quo,” once a Pandora’s box of this nature has been opened, it can’t be closed again. In fact, there is nothing that can be done to put such knowledge back inside. As David tells his TV father, George, after being jailed for helping Bill paint a scandalous mural in color, “Nothing went wrong. People change.” This in response to George asking, “One minute, everything’s fine, the next—what went wrong?”

The comfortableness of things staying the same is, in many ways, as intoxicating as the urge to blow up one’s entire life and do something completely different. For some, it will be the former that wins out, while, for others, it simply has to be the latter. Incredulously, George echoes, “People change?” David affirms, “Yeah, people change.” Not liking this answer, George further demands, “Can they change back?” Sympathetically, David offers, “I don’t know. I think it’s harder.” Like trying to put a butterfly back into a cocoon. Or, in Guy’s case, ever having to return to the NPC life he was saddled with for so long. He, just as the denizens of Pleasantville, has seen the light in glorious technicolor and there’s no turning back now. Would that we could all say the same after having decided to continue to stick with the oppressive and dysfunctional systems blacklighted in the wake of coronavirus.