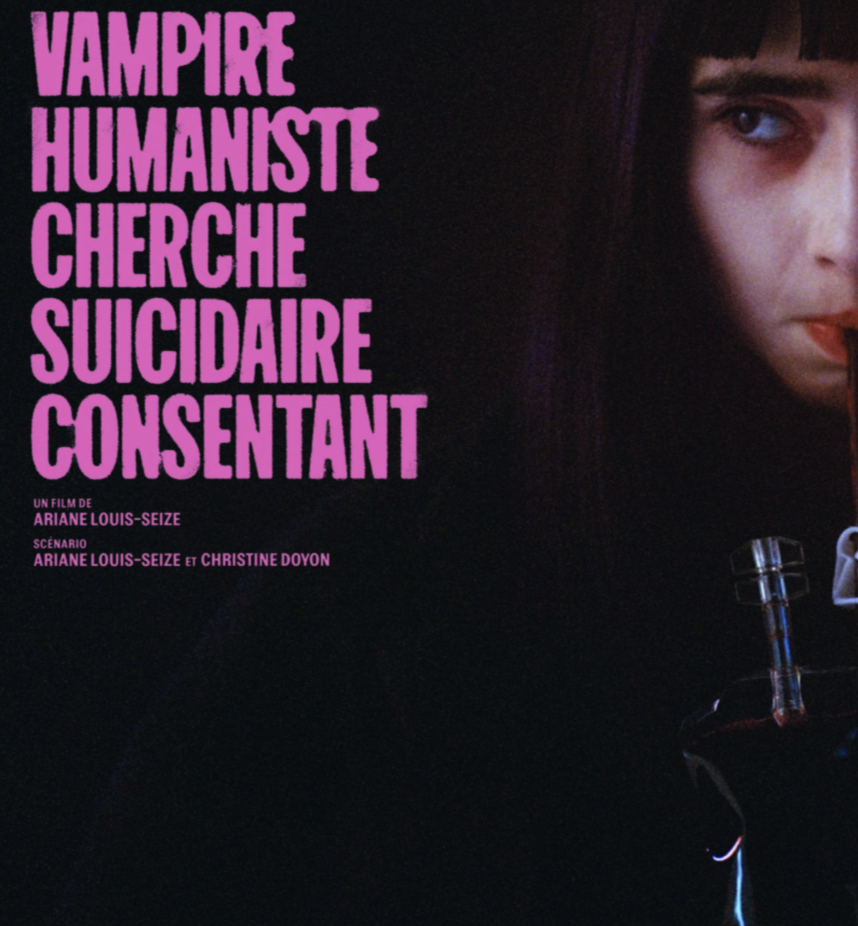

Ever since 2016, writer-director Ariane Louis-Seize has been building up to her debut, Humanist Vampire Seeking Consenting Suicidal Person (or, in French, Vampire humaniste cherche suicidaire consentant). This started with the Québécoise filmmaker directing a total of eight short films before finally transitioning into her “big one.” And it is that, despite its “quietness.” For the concept alone is something rather monumental despite its simplicity: a blood-dependent vampire is morally opposed to killing humans for sustenance.

The story begins during a birthday party, of sorts, for the humanist vampire in question, Sasha (played by Lilas-Rose Cantin and, later, Sara Montpetit), who is still just a child (one that channels a touch of Wednesday Addams as both a little girl and a teenager). Her parents, Aurélien (Steve Laplante) and Georgette (Sophie Cadieux), as well as her aunt, Victorine (Marie Brassard), and cousin, Denise (played by Valence Laroche and, later, Noémie O’Farrell), are all in attendance as they wait to reveal something very sinister to her: the clown that Aunt Victorine has “ordered” to entertain Sasha is actually going to be their dinner and dessert.

As Sasha’s first experience watching such a horrifying practice, rather than being delighted as her fellow vampires are, she’s absolutely traumatized. She continues to think about the brutal murder of the clown at the mouths of her barbaric family to the point where Aurélien and Georgette decide to take her to see a therapist (who knew, vampires have their own set of therapists and doctors). The advice given is that they should let Sasha stay there to be, essentially, studied and experimented on until they can get her to act like a “proper” vampire (this includes making her watch certain hideous scenes from movies to gauge her emotional responses à la Alex in A Clockwork Orange).

Although Georgette is all for allowing Sasha to remain “institutionalized,” Aurélien is appalled by the idea of leaving his daughter there, deciding that she’ll simply have to drink from pre-made pochettes of blood until she can learn—in her own way and on her own time—how to be a real vampire. One that gleefully attacks and bites the shit out of human prey.

Alas, by the time Sasha is a teenager, there’s still no change in her behavior. She remains reliant on her parents, mainly Georgette, to hunt her food and provide it for her in what amounts to a sanitized “blood juicebox.” She’s sort of like an American who can only eat their meat or seafood if it’s provided in the least “messy” way possible (you know, like no heads on shrimp or fish—that sort of thing). When she’s not drinking from her “ready-made” pochettes, she’s playing her keyboard for a bit of extra money in front of the twenty-four-hour copy and fax place (it’s Quebec, so, no matter what year it is, there’s always this sense that we’re still in the 90s). It is there that she first catches sight of Paul (Félix-Antoine Bénard) across the street. More specifically, Paul perched on the roof of the bowling alley where he works, contemplating jumping to his death.

This sight ignites something in Sasha that she didn’t know was dormant: the urge to kill—but humanely. Because, yes, her human side seems to have far more control over her emotions than her vampire one. That is, until noticing that Paul obviously wants to kill himself. Waiting for him to finish his shift at the bowling alley, Sasha stalks him into the night, following him to the next high place he wants to try jumping from. Only this time, he can feel her presence, running in terror when he notices her hovering above him like a ghoulish serial killer. The only problem is, he runs right into a shipping container and knocks himself out.

When Sasha approaches him and sees the blood trickling down his forehead, something unprecedented happens: her fangs actually come out of their own volition. The “automatic response” her family has been waiting years for. Scandalized by the sudden appearance of her “inherent nature,” Sasha leaves a semi-conscious Paul on the ground and scurries back home, where she tries to hide from her parents the fact that her fangs have come out. Unfortunately, they corner her in her room just as she returns, wanting to talk to her about the shocking thing they found in her room: food made for humans (namely, a cookie that someone threw into her keyboard case).

Forgetting to talk in such a way so as to keep her top lip covering her fangs as she insists she wasn’t going to eat the cookie, Aurélien and Georgette gasp at the revelation of her teeth. Immediately after, it is Georgette who talks Aurélien into forcing Sasha to go live with Cousin Denise so that the latter can show her the ropes of hunting. Now that Sasha’s fangs have emerged, she has no excuse. Despite all her best efforts to avoid it, she’s a vampire. In this sense, Humanist Vampire Seeking Consenting Suicidal Person is very much a movie about coming to terms with, let’s say, your “heritage.” About how trying to deny it or suppress it will never work—but that perhaps acknowledgement is the first step toward amending how “your kind” can behave.

Over the course of the narrative (which, at times, offers faint shades of Xavier Dolan’s work paired with What We Do in the Shadows), Sasha comes to realize, with Paul’s help, that there is a “workaround,” so to speak, to being a vampire who despises the idea of killing humans. Or at least humans who don’t want to die. Indeed, it’s Paul who comes up with the concept of being a “humanist vampire.” For, after Sasha abandons him on that first night, the two cross paths again at a suicide support group (with Sasha getting the bright idea to hunt for humans in this setting instead). Paul, a fellow outsider among his own kind, soon takes a shine to Sasha (and vice versa) despite what she tried to do to him. In fact, Paul insists she still wants her to kill him. Bleed him dry, as it were. But the more time Sasha spends with him, the more she realizes she can’t hurt him. Not just because she doesn’t believe he really wants to die, but because, well, she’s fallen in love—the most human “foible” of all.

With this element of the story, there’s a certain Romeo and Juliet (not Twilight) angle that develops…after all, how can a human and a vampire be together without one of them making a very significant sacrifice (usually, the human)? Unless, of course, doing whatever it takes to be with the one you love doesn’t feel like a sacrifice at all, but a necessity.

[…] Genna Rivieccio Source link […]