It’s a “fantasy” that keeps coming up again and again. Perhaps because it feels so close to becoming a reality, what with Grimes assuring us that AI is not the future, but the present. As such, the technology to create the “perfect” humanoid partner is something that those with morality-based misgivings, like Dr. Alma Felser (Maren Eggert, who has a certain Greta Gerwig vibe), will have to contend with as a demand increases. After all, human partners have shown themselves to be highly ineffective and disappointing, so why wouldn’t the average person want to try this new “foolproof” approach?

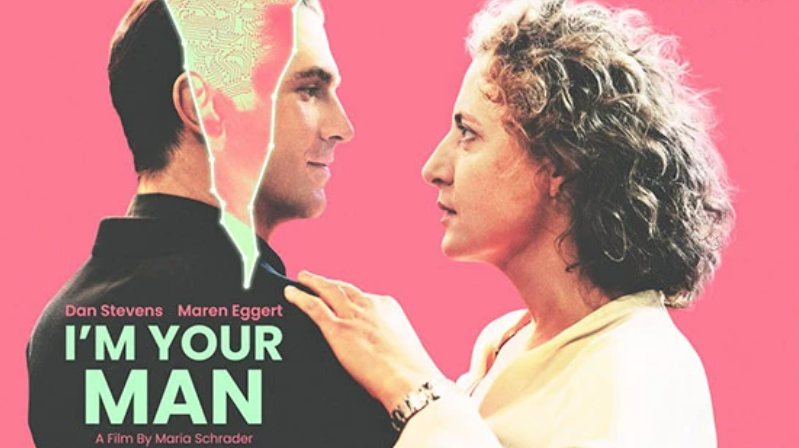

As one of ten people enlisted to critique their robots and provide an assessment as to whether or not they feel these “beings” should be given not only the “green light,” but also things like human rights, Alma is only obliged to engage in this cockamamie experiment because her supervisor, Roger (Falilou Seck), tempts her with the promise of more funding for her and her research team to go to Chicago and look at cuneiform tablets up close and personal. Although Alma is a woman of “reason” and “science,” it doesn’t mean she believes that love can be “generated” through an algorithm. Tom (Dan Stevens), on the other hand, is certain he was quite literally made for Alma. Alas, he was not prepared to contend with her unique brand of stubborn aversion. Nor the fact that a comment such as, “Your eyes are like two mountain lakes I could sink into” does not fill her heart with love, so much as complete disgust. Scoffing at the results after so much data and money were funneled into the project, Alma continues to reluctantly “humor” the experiment, but only to a certain degree. She certainly isn’t about to let Tom sleep in the same bed with her.

But it doesn’t take long for Alma to see that Tom does have some benefits that human men do not. For example, oh how lovely it would be to get a man to delete gross words from his vocabulary. Words he doesn’t even imagine to be gross. Like when Tom says, “Peachy” and Alma gives him a death stare that makes him realize he shouldn’t ever say it again. She confirms, “You can also delete ‘you betcha,’ ‘okie dokie’ and ‘toodle-oo.’”

As Tom learns more about Alma’s complexities, including her strained relationship with her ex and having to deal with her curmudgeonly father (who suffers from dementia), he seems to mold himself to her varying mood shifts. Yet this only enrages her all the more, as she wants him to have some sort of reaction. Not constantly be so “perfect.” Nonetheless, she can’t help but admit she’s grown used to this “presence” in her midst. And it’s more than the kind of presence that comes from simply having a dog or a cat. It’s deeper than that (as she phrases it at one point, “I wish I’d never met you. Life without you is now just a life without you”). Plus, Tom can fuck. Oh, how Tom can fuck. But rather than this “heartening” Alma, it only propels her further away from him. For she suddenly has the epiphany that everything she’s doing is nothing more than a performance—from putting a blanket on Tom even though she knows he can’t get cold to trying to make him the perfect egg even though she knows he doesn’t need to eat. Worse still, she’s only performing for herself, like a more elaborate form of self-delusion. And that’s what, to her, makes it all even sadder. To this, Tom asks, “Don’t humans say, ‘Love knows no bounds’?” She balks, “That’s always been a lie.” And she’s not wrong. Every human has a dealbreaker, one they simply can’t overlook for the sake of “love.” Even a “love” that’s as easy as it should be with a robot.

Co-written by Jan Schomburg and Maria Schrader (who also directed), I’m Your Man bears similarities to a Black Mirror episode that can no longer really be called “futuristic” or even “dystopian”—it’s merely “the next ‘logical’ step” in the technology available to humankind. Like Alma, there are many who feel, “There’s no doubt that a humanoid robot tailored to individual preferences can not only replace a partner, but can even seem to be the better partner. They fulfill our longings, satisfy our desires and eliminate our feeling of being alone. They make us happy, and what could be wrong with being happy?” Naturally, there’s often quite a bit wrong with what humans brand as “happiness.” Just look at the post-war boom in America that prompted the worship of capitalism as the end all, be all of pursuits.

The same goes for the instant gratification model of robots that can cater to every romantic and sexual whim. So it is that Alma adds to her evaluation, “But are humans really intended to have all their needs met at the push of the button?” On a side note, they certainly seem to think they’re meant to in the twenty-first century, hence all the disappointment in how goddamn ghetto this epoch has turned out to be. The rumination continues, “Is it not our unfulfilled longing, our imagination and our unending pursuit of happiness that are the source of our humanity? If we allow humanoids as spouses, we will create a society of addicts, gorged and weary from having their needs permanently met and from a constant flow of personal acknowledgement. What impetus would we have to confront conventional individuals, to challenge ourselves, to endure conflict, to change? It’s to be expected that anyone who lives with a humanoid long-term will become incapable of sustaining normal human contact.” Or is that mode of thinking on the level of paranoia that caused a movie like Reefer Madness to be made? What’s more, humanoids like Tom are, “these days,” actually more animated and lively than the human drones we see usually affixed to their screens.

Whatever the case, sooner or later, we’re bound to find out—since institutions would rather float money into enterprises such as these as opposed to maybe fixing all the shit that creates so many human problems before introducing a new ersatz race of them into the mix (presumably designed to stamp us out altogether whether intentionally or not—after all, humanoids don’t need food or cash to survive in a climate apocalypse; better still, they don’t “desire” things).

I’m Your Man is not the first to explore the concept of what it would mean to have access to such a, shall we say, “intuitive” and “attentive” partner (the recent HBO show, Made For Love, also explores that to a certain extent), but it is the first to do it with such a philosophical and morally obligated slant.

“What is the saddest thing you can think of?” Alma demands of Tom on their first “date,” wanting to throw him off in some way. Without missing a beat, he provides the cliché answer, “Dying alone.” But, like Troy Dyer in Reality Bites says, “Everyone dies all by himself.” We might not crawl under the porch to do it or deliberately seek some other solitary place like most animals, but dying alone—regardless of being in a relationship or not—is bound to happen. No one can make the journey with you, nor can they “ease the pain” when it finally occurs. Regardless, most would prefer to do it with a humanoid at their side when the presence of an actual human that loves them is not accessible. And maybe that’s the core message of I’m Your Man: the importance of having even more advanced tools at our disposal to help sustain the delusions we cling to in order to cope with the one reality that no amount of power, prestige or money can negate: death renders everything meaningless.

When you’re in the ground one day, you won’t be conscious of whether someone ever loved you, if you spawned, if you were a societal failure. And that inevitable lack of consciousness, rather than being a comfort, seems to unsettle people more than anything else as they make the desperate scramble to “find someone”—anyone—who can imbue it all with “purpose” and “value.” Even if that person is really only a phantasm.