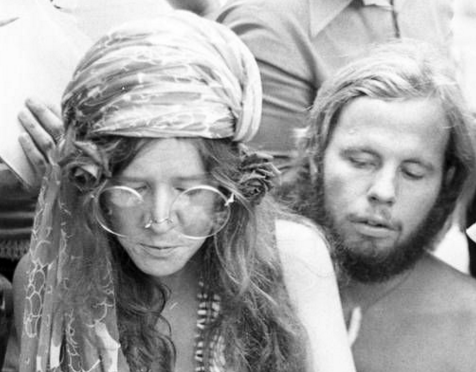

Everything emanating from Janis Joplin’s being suggested the specific sort of brokenness that can only come from being insufficiently loved. Amy J. Berg’s latest film, Janis: Little Girl Blue, puts a spotlight on this fact more openly than any other piece that has explored the nature of Joplin’s greatness.

Unfortunately, it came from the condemnation of being an outcast, and the pain inflicted on her by the men she loved, who could never seem to stick around. Narrated by Cat Power through old letters Joplin sent home to her parents from San Francisco and other parts of the country, we’re given a snapshot of her loneliness and uncertainty not just through her own words, but through the interviews of people like Powell St. John, who Joplin played in Austin clubs with in a band called The Waller Creek Boys in her pre-fame days. As St. John puts it, “Janis became one of the boys.” St. John then recounts how, while Joplin was at college in Austin, the fraternities came together to nominate her as the ugliest man, a crushing blow that did nothing to help repair Joplin’s already damaged self-image and sense of self-worth (she had spent her whole life feeling ugly and un-feminine). It was soon after that she moved to San Francisco, settling in the North Beach area where she would hang around a bar called The Anxious Asp. It was here she met a woman who she would move in with and briefly dabble in homosexuality–perhaps a strong indication of how ill-at-ease she felt trusting men. That is, until Peter de Blanc came along. The two built a torrid love affair around drugs, with Joplin favoring methedrine. Her emaciated appearance eventually led to her friends pooling their money together for a bus ticket to send Joplin back to her hometown in Texas, Port Arthur.

Though she tried her best to fall in line again, get clean and graduate from college, it didn’t help matters when de Blanc betrayed her by marrying someone else–even though he was engaged to her and had come to her house to ask her parents for her hand in marriage. Maybe it was in that moment that Joplin remembered hearing that record by Odetta that led her to discover her talent as she burst into a perfect imitation of the under-appreciated blues singer. And even though she had tried her hand at the choir before, there was something different and special about this moment. It was an instant in which she knew she was not built for the conventional lifestyle of what was expected of a woman. This, however, did not stop her yearnings for a man.

Even in the content of her lyrics, there was the quality of feeling second best, of being a woman a man could turn to if he had been thrown over by another. This is well-exhibited in “Tell Mama,” in which she sings, “You thought you had found yourself a good girl/One who would love you and give you the world/Then you find, babe, that you’ve been misused/Come to me, honey, I’ll do what you choose/I want you to/Well, tell mama/Tell all about it.” She’s even clever enough to invoke the not so subconscious Oedipal need most males have–that’s how accustomed she was to using every line to attract a man’s interest.

Back in San Francisco, the momentum began to pick up for Joplin, especially after she joined Haight-Ashbury beloved band Big Brother and the Holding Company. It was after performing at the Monterey Pop Festival that Joplin broke completely into the limelight. And yet, it wasn’t quite enough. As she states in one of her letters at the beginning of the documentary, there’s more to being famous than talent. “The deciding factor’s ambition. Or how much you need. Need to be loved and need to be proud of yourself. And I guess that’s what ambition is. It’s not all depraved quests for position or money. Maybe it’s for love, lots of love.” Joplin was never able to find that love. Even when she thought she had in David Niehaus, a fellow wanderer who happened upon Joplin at Ipanema Beach while she was in Rio for Carnival and fell in love with her enough to divert his plans for going to North Africa. But when they returned to the United States together, her reversion to heroin sent him packing. It was a betrayal she would never get over.

Niehaus describes, “She could feel everybody’s pain. That’s one of the reasons she did heroin was so she didn’t have to be involved with everybody else’s life. Most people can be oblivious to what’s going on around them, but Janis couldn’t. She couldn’t block it out.” It wouldn’t be until, tragically, one day after Joplin’s death that Niehaus reached out to her with a telegram asking her to go to Kathmandu with him. But, as Janis: Little Girl Blue illustrates, people never took the time on Joplin that she required until it was too late.