A shiva after turning a trick is bad enough, of course. But a shiva where the john you just turned the trick for shows up? Unbearable. Alas, this is the fate that befalls our fraught heroine, Danielle (Rachel Sennott), in Emma Seligman’s feature debut, Shiva Baby. Adapted from her own 2018 short film, the story still doesn’t clear the ninety-minute mark despite being “fleshed out” (no prostitute pun intended). Yet that doesn’t mean Seligman doesn’t cram as much psychological action-packedness as possible into the one-location narrative.

Before the primary milieu—someone’s house for a shiva—takes over, Danielle appears briefly in the SoHo apartment of Max (Danny Deferrari), her seemingly favorite sugar daddy. After she finishes banging him, he asks, “Busy day?” She lies, “Yeah… I have this brunch thing I have to get ready for.” He probes, “Another client?” She lies again, “Yes…” He ribs, “Does he have hair? Does he have teeth?” She assures, “Yes.” He goads, “How are you gonna get through law school when you’re busy screwin’ around with these guys?” She mock repeats his paternalistic concern that apparently no Jewish man can resist emanating. He then reminds her to put back on the bracelet he gave her—an expensive-looking gold trinket that clearly means they’re more than just people who met on an app for a few one-offs.

For Danielle, it’s a source of affection she can’t seem to get from anyone else in her own life. Mainly because everyone else is aware that she’s totally rudderless and without a plan. Instead, Max thinks she’s going to law school to make big things happen in business, or whatever. “I think it’s really great to support females, particularly female entrepreneurs,” he says to her in a way that can only come across as belittling after slipping her the cash. She glibly retorts, “Okay, cool.” She’s not really in a position to lecture him on the nuances of microaggressive misogyny. In the meantime, her mother, Debbie (Polly Draper), has already been calling and leaving her a message about getting to the shiva on time. Since she couldn’t seem to be bothered to make it to the funeral.

Showing up to the house, Danielle is met with what will be the first in a series of stressful dialogues—and it’s a stress level that’s immediately exacerbated when she catches sight of her longtime (ex) best friend, Maya (Molly Gordon), across the street. Yes, she, too, is about to enter the house to mourn. Seeing the already sexual tenseness between them, her mother warns her not to do anything embarrassing today. When Danielle makes a crack about how she should feel “so grateful” she didn’t get kicked out of the house when her parents found about her “little dalliance” with Maya, Debbie retorts, “You’re not in our house, you’re just on our payroll.”

Debbie then turns on her heel to follow Danielle’s dad, Joel (Fred Melamed), inside. Danielle calls out, “Wait mom! Who died?” Cut to the interior of the house where Danielle wings it with generic phrases like, “So sorry for your loss.” In short, she basically showed up for the food (and to “sing for her supper,” as it were, in terms of giving her parents something for the money they pour into her). That’s certainly the inference made by all the overbearing Jewish mothers who see how “emaciated” she looks.

As Danielle walks through the room, trying to keep the exchanges as cursory as possible, someone accidentally mistakes her for Maya. Indeed, their “similar appearance” (really, just brown hair) will be remarked upon by Max later as well—which is how it comes out that the two were also lovers. The Jewish girls as lesbian “trend” began most overtly with 2017’s Disobedience (Rachel McAdams’ follow-up lesbian foray after 2012’s Passion), and it’s long been a speculative secret that the religion provides something of a “breeding ground” for lesbianic experimentation.

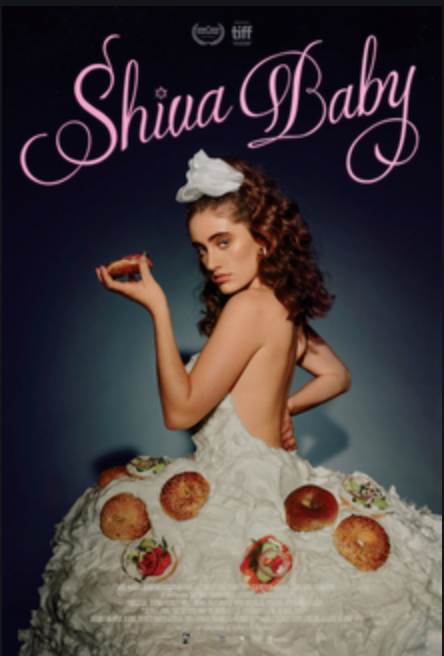

Whispers (by Jewish women’s standards) of, “She’s lost so much weight” and “Is she okay?” indicate Danielle might have been much more… zaftig in the past. A fact that, if not indicated by her sudden stress eating (hence, the now iconic movie poster), is later confirmed when her father describes Danielle’s “awkward” (read: plump) phase. It is here that one is reminded another Jewish staple from the past year: Melissa Broder’s Milk Fed. Also exploring a Jewish woman’s struggle with her eating habits and sexuality, there are undeniable parallels between this film and Broder’s coup de grâce in Jewish literature.

Turning tricks a.k.a. being on a Seeking Arrangements-type app, for Danielle, translates to telling her parents she “babysits”—which isn’t that far off the mark. You know, considering most men are perpetual toddlers. As the plot unfolds, the revelation that she gets money from her parents while also doing this endlessly affronts the likes of Max and Maya, the former being unable to wrap his head around a girl doing something so “base” without “needing” to.

In the background of it all is Max’s wife, Kim (Dianna Agron). Not just any wife, but a shiksa, “girl boss” wife. If that previously concealed information wasn’t bad enough for Danielle, he also has a newborn child (who happens to look just as Aryan as her mother). The anxiety of all these mounting social pressures begin to weigh increasingly on Danielle—eating another bagel here, trying to suck Max off in the bathroom there. And it all adds up to knowing just one thing for sure about her directionless existence: she really does still care about Maya.

While the premise of Shiva Baby is such a simple concept, the fact that every detail is imbued with the tightly-wound nature of Jewish psychosis—particularly at a shiva—makes the film feel laden with more action than it technically has. This, too, is additionally heightened by Ariel Marx’s thriller-esque score.

As the fever pitch of Danielle’s anxiety (therefore the viewer’s) reaches a crescendo, a scene of various shiva attendees stuffing their faces through the lens of a close-up shot only adds to the tenseness and overall grotesquerie of the day. In short, at every turn, she’s met with some fresh horror to add to her anxiety.

Maybe that’s why the only thing that has ever really made her feel “in control,” thus far, has been “hooking.” “It felt nice to, like, have power and, like, be appreciated,” Danielle sums up of her “whoredom” when Maya asks why she did it. Perhaps because being stifled and subjugated by her parents (and the religion that created their propensity for this kind of parenting) for so long drove her to try to experience this feeling by any means necessary. And in the end, the shiva serves as a sort of rebirth for her own future purposes—even if enduring it meant being forced to have, in essence, a public mental breakdown. Which everyone will likely be talking about for years to come.