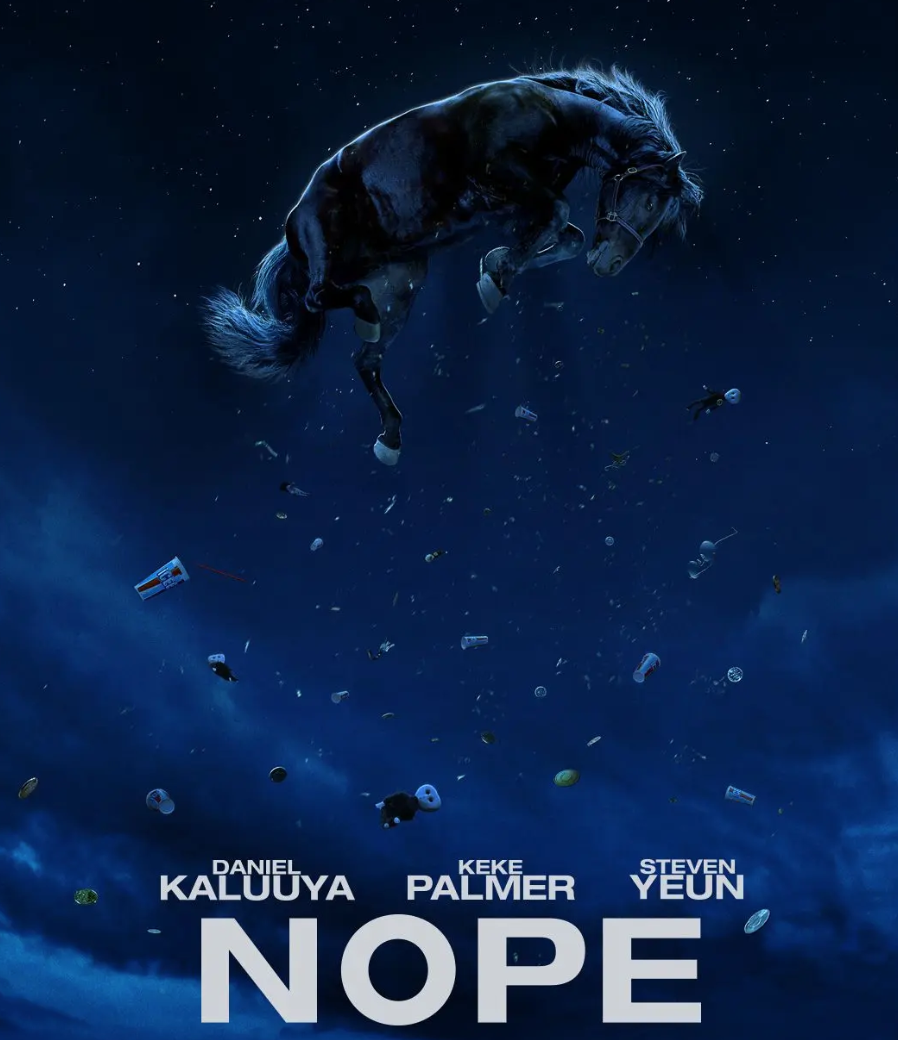

As it’s widely known that Guy Debord already has the claim on the title The Society of the Spectacle, maybe Jordan Peele was feeling just “fuck it” enough to go for something more catch-phrasey and simple like Nope (which now means there can never be a biopic called Knope about Leslie Knope, much to the dismay of Amy Poehler and Parks and Recreation fans). Even if Daniel Kaluuya said Peele named the movie as such because “that’s the reaction that Black people will have when they watch it.” And yes, OJ (Kaluuya) does say it many times throughout the unfolding of the plot.

But before we even get into OJ Haywood’s realm (where he’s called out by a white woman for having the name OJ), Peele sets the stage for the entire crux of what the film seeks to reflect: the collective obsession with spectacle. No matter at what cost. From the moment we’re given what appears to be an extremely random, non sequitur opening involving a chimp, the tension we feel is mitigated only, perhaps, by our perverse desire to see more. Know more. And because knowing more means being exposed to more potentially bleak shit, we start to become desensitized to the spectacle. Grotesque and horror show-oriented as it is (see: the January 6th hearings).

In Debord’s signature treatise, he argues (rightly) that “all that once was directly lived has become mere representation.” He couldn’t have known how eerily accurate that assessment would be with the dawn of social media, itself an offshoot of what film germinally established in the 1890s. And it was with the advent of cinema that society changed gradually, then suddenly—like Mike in The Sun Also Rises said about going bankrupt. Suddenly “life imitating art” was everywhere, with art imitating life being a quaint notion of the painterly past. With that newly-minted philosophy, everyone wanted to be “discovered” (especially when that lore about Lana Turner at Schwab’s drugstore got out) in order to imitate the simulacrum that life in the twentieth century had become.

The continued evolution of “the screen’s” mesmerizing capabilities (still best evinced by Millie in Fahrenheit 451) when it came to luring the masses was all working in the film industry’s favor until television began to creep up on the movie moguls. At first, it seemed like a passing “curiosity,” shown at the 1939 World’s Fair. But by the early 1950s, the studio heads were starting to get the picture: their medium was old news. And yet, relying on that tried-and-true trick to entice the hordes, the studios thought to introduce new improvements to their films’ spectacle-driven capabilities that TV wouldn’t be able to compete with. Enter Technicolor, CinemaScope and stereophonic sound. All hat tricks designed to prove to the screen enthusiast that nothing could ever beat the sense of spectacle provided in a movie theater.

To that point, Peele was inspired by spectacle movies like King Kong when he was working on the idea during the pandemic, remarking, “I wrote it in a time when we were a little bit worried about the future of cinema [side note: most people still are]. So the first thing I knew is I wanted to create a spectacle. I wanted to create something that the audience would have to come see.” Hence, filming Nope in IMAX with the help of his trusty cinematographer, Hoyte van Hoytema. It is he who somehow seems to be the loose inspiration for Antlers Holst (Michael Wincott), the man eventually enlisted by OJ and his sister, Emerald (Keke Palmer), to capture The Shot. You know, the money shot that will send the masses into a frenzy over what they’re seeing: actual proof of alien existence. Because, while Peele might have transitioned to horror, he hasn’t lost his sense of humor by any means, playing up the comedic (though also extremely depressing) angle of how, more than being afraid of aliens attacking them, OJ and Emerald are first and foremost concerned with monetizing their presence on the ranch.

The very ranch where their dad, Otis Sr. (Keith David), just dropped dead, with some hospital in Santa Clarita citing the objects that fell from the sky and landed on his head as the cause of death. But where did the objects really come from? They were the detritus of a spaceship’s unwanted elements of a snack. Because, unlike other “alien movies,” Peele’s presents the spaceship itself as the sentient, animal meat-thirsting being. There are not “little green men” inside of it, per se. The thing itself is just a gaping hole of want and need. And in this regard, it is a mirror of humans gorging themselves on spectacle.

Case in point, when Emerald and Angel (Brandon Perea), the Fry’s electronics guy who shows up to install some camera equipment to capture the shot and then ends up getting majorly involved (because, of course, he can’t resist the potential spectacle), are trapped together inside the house to avoid being sucked up by the spaceship, the latter entity proceeds to play back the screeching noises of human screams. The shrieks of simultaneous horror-delight. When Angel asks Emerald what that sound is, she replies, “It’s us.” The foreshadowing to this sonic moment was already established at the beginning of Nope, when the dialogue from a 90s sitcom called Gordy’s Home is played back just before the aforementioned “random” chimpanzee scene. The chimp in question is bloodied, having clearly just snacked on some humans. Poking at the body next to him, we later see that same girl’s blood-stained shoe in an encasement in a secret room curated by a former cast member of the show, Ricky “Jupe” Park (Steven Yeun).

In the present day, Ricky owns the theme park called Jupiter’s Claim next to the Haywood ranch. He’s found a way to monetize Western “culture” and is looking to expand by purchasing some of OJ’s horses as he falls into his own financial disarray after Otis’ death. The fact that the majestic horses the Haywoods own are reduced to being shilled as “show ponies” for second-rate productions starring actors of dubious talent is another testament to the ways in which we are conditioned to taint everything that’s pure for the sake of profit, especially Nature. The chimp being pushed to its brink and snapping at the cast on Gordy’s Home is further evidence of that. But, of course, humans won’t think to blame themselves, instead merely choosing to bar chimpanzees (or monkeys of any kind, really) from being used on sets anymore as a direct result of that “incident.” The horse being wielded by OJ also has a moment where it looks like it could really snap because the director isn’t acknowledging that it’s an animal, one unmotivated by money. If it isn’t in the mood to do something, it won’t. And again, that’s because, apart from humans, money means nothing to the animal kingdom. It is not a “motivator,” but a decimator. When the camera flash goes off in the horse’s eye, it gets spooked and starts bucking. OJ is sensitive enough to his horse’s needs not to push him, but in the end, it gets Haywood’s Hollywood Horses fired from the job.

In contrast to Jupe, who learned long ago how to “alchemize” any sense of trauma into comedy or profit, OJ isn’t that amused when Jupe regales him and Emerald (who comes along for the business meeting to discuss the sale of certain horses) with “the story” of the chimp that went crazy on set. But rather than the real story, he keeps referring to the SNL sketch about it… mentioning Chris Kattan a lot—in fact, never has Kattan been given so much credit as a gifted actor. Plus, Kattan did have a recurring “monkey sketch” in the 90s centered on a character called Mr. Peepers. And, speaking of SNL, another relevant sketch to the motif of Nope is one from 2011 featuring Bill Hader as the host of Dateline. As he proceeds to get off on every mention of bodily carnage, it’s easy to see society at large reflected back in his orgasmic reactions to horror. Tragedy porn, if you will. It’s part of why true crime as a genre has only continued to flourish. Why a company like TMZ still thrives (much to Britney Spears’ dismay). Certainly, Peele isn’t going to let a commentary on said tabloid journalism pass him by in Nope, as a small plot point about a TMZ reporter appearing on the ranch serves to both contrast and complement Antlers’ fixation on getting the perfect shot—spurred by the arrival of “golden hour.” This is what ultimately kills him the in the same fashion as the TMZ reporter, making them indistinguishable from one another even if Antlers’ “craft” is deemed the more “legitimate” one because it’s “true art.” In the end, however, both are in pursuit of the footage that will get the audience’s rocks off.

The continued allusion in Nope to Debord’s tome and the fact that we’re all performing versions of reality for ourselves was best described in a meme posted by Julia Fox to her Instagram story. That pixelated vomiting image, this time captioned with something to the effect to, “Me thinking about when I was living in the moment when I could have been using it for content.” This idea that everything we do—even the most mundane of shit—is meant to somehow be “monetized” for mass consumption is Debord’s The Society of Spectacle as even he could never have imagined. In another recent commentary on our spectacle-obsessed society, Billie Eilish’s single, “TV,” explores the grim nature of humanity’s schadenfreude-oriented fascination, so enraptured and entranced by something like “movie stars on trial” (Johnny Depp and Amber Heard) that they barely notice when their human rights are gradually then suddenly stripped away (i.e., the overturning of Roe v. Wade).

The meta element, of course, is that Peele makes his living off spectacle, using this very film to draw audiences in and digest the more “wowing” scenes while agog. Despite this, Peele seeks to affect on a deeper level, and it wouldn’t be a Peele movie without a searing racial commentary. Hence, the repeated story about how the Haywoods’ great-great-great-grandfather was the jockey riding in the first film strip ever made (“since the moment motion pictures could move, we had skin in the game”). The Haywoods’ legacy of their great-great-great-grandfather being the subject in the first assembly of images to create a film strip is based on the photographs Eadweard Muybridge took of an unknown Black man riding a horse in 1878. The setting of the film is additionally part of Peele subverting the stereotype that anything with a Western or ranch “flavor” can’t include Black people—because if you think of any Western, it’s always white men that come to mind. This being relevant to the inherent racism of Hollywood, despite its frequent claims of being woke, liberal, progressive, etc. Obviously, that’s not the case. What’s more, Peele would like to remind everyone of a Sidney Poitier Western called Buck and the Preacher, remarking that it was “the first film that I know of that had Black cowboys represented in it. The myth that cowboys were just white guys running around, it’s just not true, but we don’t know that because of Hollywood and the romanticized view of a very brutalized era.” It seems even Beyoncé wants to reclaim Blackness in a Western tableau by getting on board with the Black cowboy motif for Renaissance (nonetheless, let us not forget that Madonna blazed the “fabulously glamorous cowgirl” trail via 2000’s Music visuals).

Regardless of re-inserting Black people into “white spaces,” Peele can’t change the fact that creepy goings-on will always take place at a remote ranch. For Agua Dulce might just as well have been the milieu where Charles Manson raised his “fam” were Spahn Ranch unavailable. And as he turns to Emerald at one point to ask, “What’s a bad miracle? They got a word for that?” we have to wonder if, maybe, in the modern age, that word is spectacle.

At the beginning of Nope, Peele uses a quote from a prophet named Nahum in the Bible to establish the impending tone: “I will cast abominable filth at you, make you vile, make you a spectacle.” But in truth, humanity doesn’t really need a carnivorous spaceship to do that, they already do it to themselves just fine.