As Lana Del Rey begins to roll out the audio for her spoken word poetry album, Violet Bent Backwards Over the Grass, while we await its release in literary form at the end of September, she has offered as its first “single,” “LA Who Am I To Love You.” Whether told completely from her perspective or as an amalgam of all the damaged girls who have come to LA after years spent dreaming of and idolizing it, is at one’s discretion. Knowing Del Rey, it’s a composite–autobiography meets the legend of others meets her own self-created folklore (even before Taylor came along).

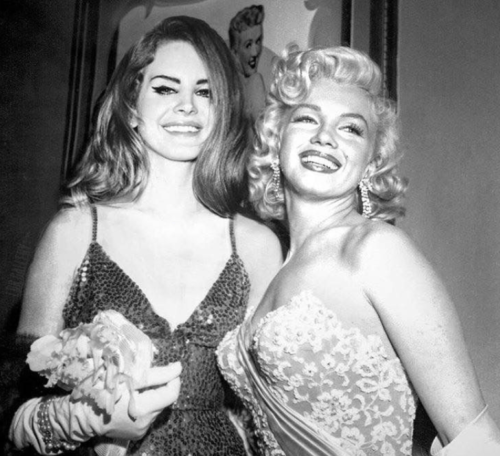

To the point of the latter speculation, the fact that she posted an image of herself with a typewriter getting on a private jet next to the presumed billionaire in question as a nod to mentioning this very scene in the poem leads one to believe it holds many truths about her own life. And yet, all over the narrative is the painted image and tragedy of Norma Jeane Baker, herself no transplant to the city, but born in LA and raised in nearby Hawthorne, always just at the periphery of Hollywood, where her increasingly mentally unstable mother, Gladys, worked at Consolidated Film Industries as a film negative cutter. What’s more, as Lana once said in another song, “Marilyn is my mother.” And Marilyn, for many reasons, is LA. Like Lana says of herself in this poem, Marilyn Monroe, the name that would get her all the love and admiration she so desperately wanted, never had a mother. Not really. Given up to foster homes and shuffled around, Norma Jeane was also sexually taken advantage of in her preadolescence. Through all the betrayals and the false hopes that she might have finally found someone to love her unconditionally, to never leave her, LA is, ultimately, the only place that has ever been true or steadfast in its loyalty and devotion to her. Del Rey, as though speaking through the same lens, entreats, “I never had a mother, will you let me make the sun my own for now, and the ocean my son? I’m quite good at tending to things despite my upbringing, can I raise your mountains?”

Monroe, always at her happiest and most authentic when pictured or filmed in the beach setting of the California coast, echoes the same aura of Del Rey in similar photos where she’s smiling in contentment on the sun-dappled beaches (paparazzi present or not). It was as though this was the one environment on the whole planet where she could just be herself, no questions asked, no demands or expectations wielded. That Del Rey and Monroe bear a certain inverse trajectory with regard to Monroe being from the West and going to the East and Del Rey being from the East and going to the West, it can be said that Monroe felt the same way expressed by LDR about wanting to return West when she was in New York, too long away from her natural habitat.

This much is encapsulated in Del Rey’s plea, “I’m lonely, L.A., can I come home now?/I took a free ride off a billionaire and brought my typewriter and promised myself that I would stay, but/It’s just not going the way that I thought/It’s not that I feel different, and I don’t mind that it’s not hot/It’s just that I belong to no one, which means there’s only one place for me/The city not quite awake, the city not quite asleep/The city that’s still deciding how good it can be.” While Del Rey might have been speaking from San Francisco when she said this, the sentiments it echoes of Monroe in her New York phase as she attempted to fit in with the “cognoscenti” of the Arthur Miller set and the so-called “serious actors” of the Actors Studio are all too real. For someone as glistening and glittering as Monroe–someone as vulnerable and sensitive–a place like New York was inevitably going to be too dingy (even during its so-called Golden Age of the 50s and 60s), too filled with the noise of its vexing “hustle”–infecting every inhabitant with a drive to make money, to be something. While her flight from LA was driven by studio head Darryl Zanuck’s treatment of her, she would never have left otherwise, and eventually came back anyway when New York proved to be a greater trauma epicenter (concluding with her lock up at the Payne Whitney Psychiatric Hospital).

Personifying her city, treating it as Anthony Keidis did when he said, “Sometimes I feel like my only friend is the city I live in, the city of angels/Lonely as I am, together we cry,” Del Rey remarks of how it will henceforth be her real home over New York–a rare “traitor” in the annals of the city’s cultish natives. So it is that she announces, “Also, neither one of us can go back to New York/For you, are unmoving/As for me, it won’t be my city again until I’m dead/Fuck The New York Post.” And fuck New York along with it. That overrated piece of shit that was decimated long ago at Robert Moses’ hand anyway. It’s the place that’s burning, even if LA is the setting that seems to be tangibly exhibiting its flames.

LA is the only one who has ever held her right (not too tightly, but just close enough to be felt), as it was for Monroe, content in her lonely Spanish hacienda in Brentwood during the final years of her life (before the pills or the Kennedys finally did her in). To live and die in LA. That’s all a girl like Marilyn could ask for. The purest, most giving relationship she had ever known, even if LA was immune to her gushing fervor. In this regard, Del Rey offers, “I’m an orphan/A little seashell that rests upon your native shores/One of many, for sure/But because of that, I surely must love you closely to the most of anyone/For that reason, let me love you/Don’t mind my desperation/Let me hold you, not just for vacation/But for real and for forever.”

LA, the city for orphans, the city for the damaged, the unloved, the person who will do anything to get the spotlight that will get them to be loved. This is the Norma Jeane everywoman explanation for why, year after year, so many girls have flocked to the City of Angels. Or, more accurately, the City of Fallen Angels. And now that reason is immortalized by Del Rey’s own inexplicable pull to this Babylon, this alternate dimension where nothing is real and so everything is. Including the city’s propensity to cradle those who were abandoned by everyone else in their life. This ode, this love letter is the closest the city has gotten to being so appreciated in quite some time, maybe not even since the days when Norma Jeane was riding through town in her Ford Thunderbird. The quintessential picture of Americana, tears about to burst forth behind the veneer of that smile. For LA is the same dichotomy of that bliss and that sadness.