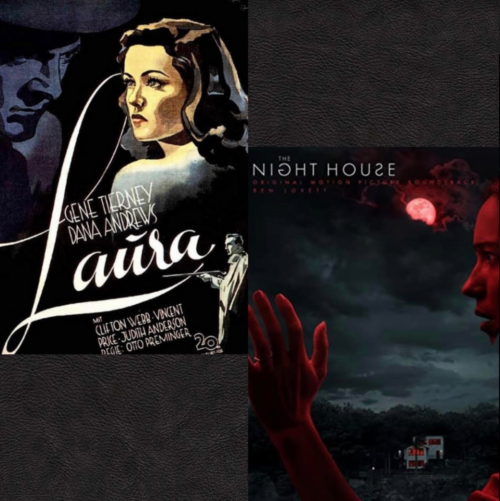

While Otto Preminger’s 1944 classic, Laura, and David Bruckner’s recent film, The Night House, might appear to be completely dissimilar, there is one essential aspect that connects these films intrinsically. The notion of everything—even murder—being justifiable with love as the reason. Indeed, the dramatic denouement of Laura finds Waldo Lydecker (Clifton Webb) being listened to by Laura Hunt (Gene Tierney) on the radio, as he broadcasts a similar rhetoric. Waldo himself has crept into her space to hear it as well. Although she’s briefly aware of some vague presence in her apartment, she seems to brush it off by simply brushing her hair. So it is that Waldo is able to approach her room as he hears the sound of his own voice saying, “And thus, as history has proved, love is eternal. It has been the strongest motivation for human actions throughout centuries. Love is stronger than life. It reaches beyond the dark shadow of death. I close this evening’s broadcast with some favorite lines from Dowson.” He then goes on to quote from Ernest Dowson’s poem, “The Shortness of Life Forbids Us Long Hopes” (translated from the Latin title).

As Laura listens to him recite, “They are not long, the weeping and the laughter,/Love and desire and hate:/I think they have no portion in us after/We pass the gate./They are not long, the days of wine and roses:/Out of a misty dream/Our path emerges for a while, then closes/Within a dream,” we watch Waldo get closer to her. Ready to kill her yet again (for he already thought that he did once, only to learn it was a different girl). It’s a classic, “If I can’t have you, no one can” moment. And everyone wants to have Laura, which makes her murder a fait accompli for Waldo. Yet it wasn’t always that way between them. Granted, as Waldo recounts to Detective Mark McPherson (Dana Andrews), assigned to investigate her murder, when they first met, there was a shaky start between them. He being so cattily rude (as is the gay man’s prerogative…no, Clifton Webb is not “passing” as straight) when she introduced herself and asked if he might help her get ahead at her ad agency by endorsing a pen. After berating her, his guilt gets the better of him and he proceeds to make it up to her by not only endorsing the pen, but also bringing her into his world of prominent New York “society.” Because of Waldo’s contacts, Laura transcends into a major player in the advertising industry.

Although she enjoys his company immensely, the tacit thing we’re meant to understand is that Waldo is, well, a gay man. Regardless of sexuality, it never stopped Hollywood before to pair someone of his age with someone of Laura’s. What’s more, the gay male narcissism of a statement like, “In my case, self-absorption is completely justified. I have never discovered any other subject quite so worthy of my attention,” cannot be mistaken. It’s almost as though Waldo took the words right out of Noël Coward’s mouth. Yet the only person who could ever take him out of his own self-absorption—much to her detriment—was Laura. The woman he calls “the best part of [him]self.” Perhaps loose code for, the person he would be if he was female. It is here that his obsession begins to make more sense for, like Buffalo Bill in The Silence of the Lambs, Waldo increasingly seems to want to possess Laura in an all too unhealthy manner. Going so far as to stave off every potential suitor by denigrating them in his column. Or, in the case of her latest “beloved,” Shelby Carpenter (a young Vincent Price), exposing him as a philanderer, a thief and a general cad. The near sick pleasure Waldo derives from informing her of these things upsets Laura almost more than the information itself.

And this is where the dynamic of their once ironclad friendship mutates. Hence, Waldo using an aphorism so indelible in our lexicon, “…the days of wine and roses.” A phrase that refers to, obviously, those sweet, pleasurable times shared with an object of one’s affection before things turn invariably sour. Because an object of affection can so rarely resist turning into an object of contempt when love is involved. Ergo that “thin line between love and hate.”

Yet this “dandy,” this “effete” man is not meant to be taken seriously as a “proper” suitor for Laura, so much as a mentor or, for those less naïve, an older gay gentleman obsessed with Laura in the way that many gay men are obsessed with women. But this was still Old Hollywood and Clifton Webb being a “confirmed bachelor” was not to have any bearing on whether he could ultimately be seen as heterosexually interested in Laura. As for that aforementioned “thin line,” it brings us to the plot of The Night House, starring Rebecca Hall as Beth, a recently widowed teacher living in Upstate New York. Specifically at a lonely lake house that didn’t feel so lonely until her husband, Owen (Evan Jonigkeit), shot himself on the boat near their dock.

Left to grapple with the inexplicability of it all—complete with a cryptic suicide note that reads: “There is nothing. Nothing is after you. You’re safe now”—Beth begins to dig deeper into Owen’s life when she goes through his phone and sees a photo of a woman at a bookstore who looks like it could be her, but not quite. It isn’t long after that she stumbles upon a “reverse floorplan” for their house, which she tries to write off until later unearthing an occult book called Caerdroia (not a real book, but based on the concept of Welsh turf mazes). That “maze” of a design gives insight into the reverse floorplan she saw, not to mention the reverse house itself, which she sees across the lake one night thanks to the windows being illuminated in the exact same way as they are at hers. Still confusing reality with dreaming (which is what happens when something so fantastical occurs at night), Beth truly can’t believe her eyes when she sees Owen at this house with various other women who resemble her. Doppelgängers that she also saw pictures of on Owen’s computer, leading her to believe he had some kind of weird fetish for this “type.”

After finding out the name of the occult bookstore where Owen bought Caerdroia, Beth also finds out that the woman he took a picture of on his phone works there after showing up to investigate more about his purchases. She confronts Madelyne (Stacy Martin) angrily, getting straight to the point about how she knows Madelyne had an affair with her husband. Madelyne is quick to assure they never slept together, but of course Beth is skeptical. Until Madelyne shows up at her house to explain further. Referring to the grotesque “voodoo statue” Beth also found among Owen’s freakier personal effects, she describes how he asked her to hold it before they embraced and kissed, leading to him starting to choke her. Just as he had choked so many other girls before her as part of the “distractions” and “diversions” to keep Death at bay. Otherwise known as the “Nothing.” The same Nothing Beth saw when she got in a car accident as a teenager in Tennessee. Clinically dead for four minutes, she later tells Owen there was nothing on the other side—something he can’t believe until the Nothing starts whispering in his ear to kill Beth.

Lo and behold, that’s when the idea for serial killing strikes him. Anything to keep the Nothing (a.k.a. the reaper) away from the woman he loves. Ergo proving, once again (just as it is the case in Laura): “…love is eternal. It has been the strongest motivation for human actions throughout centuries. Love is stronger than life. It reaches beyond the dark shadow of death.” And, in Beth’s case, that’s quite literal. There’s an instant when she truly does believe Owen has managed to reach beyond the dark shadow of death so they can have their “Ghost moment”—only to be totally sketched out by the realization that it’s Demonic Death, seducing her into killing herself by showing what Owen did. The idea of Death as the ultimate sexual release is also presented in these scenes, particularly when the Nothing binds Beth in the same position as the voodoo doll as she writhes and moans while suspended in mid-air, looking up at two different moons meant to indicate the two different dimensions she could choose between: life or the Nothing. The Nothing that has come back for her after she managed to evade it the first time. And if Death is merely the absence of life (in other words, total unconsciousness and blackness), to choose it is to choose the opposite of love. Ironic, considering how many deaths occur in Love’s name.

Owen, believing that killing himself will force the Nothing to stop pursuing Beth because it can no longer get her husband to do his bidding, ends up sending Death right into her arms. Tired of this game of cat and mouse, it announces that it wants her. Ergo, Owen evidently killed all those women for, um, Nothing. Or rather, we can look at it as him killing in the name of love—the reason that, even in modern cinema, seems to validate all psychotic behavior.

Love—whether for a human or an ideal (which extends, of course, to religion)—justifies the means to any end in both of these films. And possibly even to those viewers who might agree with the extremism that such an emotion can cause.