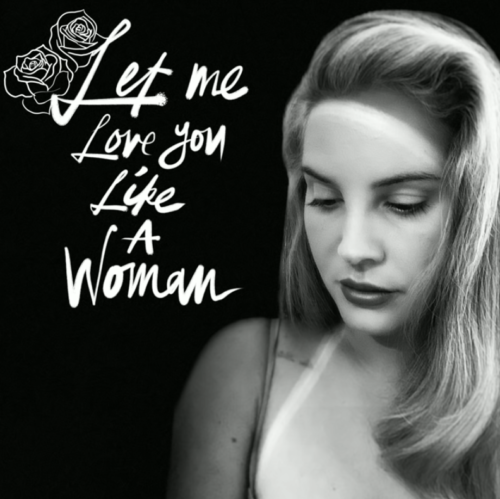

In a move that seems to continue to prove that Lana Del Rey doesn’t exactly have her finger on the pulse of what “the kids want” these days (apart from the die-hard acolytes that will question nothing she does), the title of her latest single is in and of itself indicative that she’s still trapped in a “golden” past that has given her too much tunnel vision. A past where white folk not only didn’t have to worry about petty concerns like “catering” to black people, but women were doting little servants who viewed their boyfriends or husbands as “the king.” Del Rey is most assuredly part of that latter category, particularly with the cloying content of “Let Me Love You Like A Woman,” serving as the lead track from what will be her seventh album, Chemtrails Over The Country Club.

Seven albums in almost as many years since she became famous harkens back to another singer who used to do the same: Rihanna. And it bears noting that Del Rey is all too pleased to borrow the cliche, “Shine like a diamond,” which immediately reminds one of Rihanna singing, “Shine bright like a diamond” on her 2012 single, called, what else, “Diamonds” (and let’s not forget how Del Rey already wielded a version of Rihanna’s simile on 2013’s “Young and Beautiful” with “he makes me shine like diamonds”). But Ri isn’t the only pop culture powerhouse Del Rey takes from, there’s also Buzz Lightyear (“take you to infinity”–it must have been really hard for her not to add the “and beyond”) and Prince (“we could get lost in the purple rain”). Elsewhere, she muses on being ready to leave L.A.–the very thing that has been her entire brand for the majority of her career, only for her to betray it when it needs celebrity devotion the most (in this sense, one supposes she’s not unlike Joan Didion). At the same time, maybe it’s best if someone who has lost this much of their edge goes on back to New York to hang out with James Murphy, rather than “eighty miles North or South.”

With a Bruce Springsteen storytelling shtick about how she’s from a small town, the piano instrumentation has echoes of “Video Games,” except here Del Rey transforms it (with the help of Jack Antonoff, whose balls we can assume she keeps in a Mason jar) into something more Joan Baez-oriented, which makes sense considering the pair’s recently made connection while Del Rey was on her Norman Fucking Rockwell Tour. Talking of Norman Fucking Rockwell, many have liked to speculate that the sound and lyrical themes of Chemtrails Over The Country Club will have a similar vibe, particularly since work on it already began at the time of NFR’s production. But “Let Me Love You Like A Woman” takes that 60s California hippie-dippy gimmick to a hackneyed place where the effect of Del Rey’s attempt at being “sweeping” and “grandiose” doesn’t translate as it once did.

While Del Rey’s entire canon has consisted of repurposed lines from other artists, this is the first time it so glaringly doesn’t work. Comes off as clunky and cumbersome, rather than seamless. Even those phrases that haven’t specifically been used by another already possess the genericness of the bromide. Not just the eponymous chorus in which Del Rey, in a manner that’s more cringe-worthy than endearing, insists, “Let me love you like a woman,” but also as she continues to repeat, “Let me hold you like a baby.” It’s quite uncomfortable (though at least the image of her holding Billie Eilish in her arms comes to mind before the image of her holding any man). Is this really the message she wants to reiterate after she’s already too long coddled men and their shit behavior? Evidently. After all, loving someone like a woman, in the nostalgic past where Del Rey’s sonics and narratives live, is rife with all the gender-specific tropes that entails. Like being expected to constantly forgive, and to take abuse, whether verbal, emotional or physical, with a smile.

It does feel prescient (though not in the way she had hoped–because hope is a dangerous thing for a woman like her to have) that Del Rey would comment on the song, “I feel like it’s going to be really important, but I don’t know why yet.” Perhaps because it firmly demarcates that 2020 has signaled a chasmic shift between this new decade and the last. Even with regard to LDR, who was, in the 2010s, a force to be reckoned with, at least with the baroque pop she was pushing. Here, we see a complete transmutation into some mewling wannabe version of Jewel (who also, incidentally, released a poetry book long before Del Rey). But then, one supposes it all speaks to Del Rey’s belief in the importance of (white) fragility that set off her first backlash of the year.