The tortured life of Vincent Van Gogh has long been discussed, examined and held up as a beacon of the ultimate definition of what it means to be a tortured artist. From the Academy Award-winning short Van Gogh in 1948 to the Kirk Douglas-starring Lust for Life, the fascination wrought by Van Gogh’s life and death has only increased over time. A new pinnacle of this curiosity about why the painter, seemingly so hopeful for the future just six weeks before his death, would kill himself manifests in Dorota Kobiela and Hugh Welchman’s entirely hand-painted (in the style of Van Gogh, naturally) Loving Vincent. With 125 classically trained painters involved in the creation of each dramatic frame (no need to take acid before seeing this film), the uniqueness of this biopic doesn’t merely lie in its aesthetic, but in the investigative angle it chooses to approach Van Gogh’s curious suicide.

As the postman who saw firsthand the intimate relationship Vincent shared with his brother and patron, Theo (Cezary Lukaszewicz), Joseph Roulin’s (Chris O’Dowd) commitment to delivering Vincent’s last letter before his death to Theo is of the utmost importance. Entrusting the task to his moody, chip-on-his-shoulder-wearing son, Armand (Douglas Booth), Joseph unwittingly sets in motion a personal investigation by Armand that leads to the physician that attempted to heal Vincent’s mental health in his final months, Dr. Gachet (Jerome Flynn).

Before landing in Auvers-sur-Oise, however, Armand makes a stop in Paris to speak with art dealer and supplies seller Père Tanguy (John Sessions), who informs Armand that Vincent was unique for a number of reasons, not just in that he was one of the only painters who didn’t make Paris his last stop. As Père Tanguy details, in the years before Vincent became a painter (depicted in drab black and white), he struggled to find a profession that would suit his temperament and please a family he already didn’t fit in with. In part due to his mother’s loss of her eldest son when Vincent was just a child, he could never measure up to his parents’ expectations of him–leaving Theo as his sole champion and source of encouragement.

The guilt Vincent experiences over being a financial burden to Theo only increases over time, and is speculated by Gachet’s daughter, Marguerite (Saoirse Ronan), to be a result of an argument that took place between Gachet and Vincent just before he shot himself. Armand remains incredulous, wanting to believe that someone had a hand in killing the master painter, rather than accepting that he was lonely and despairing enough to check out of this life of his own volition when he was finally on the precipice of potential fame.

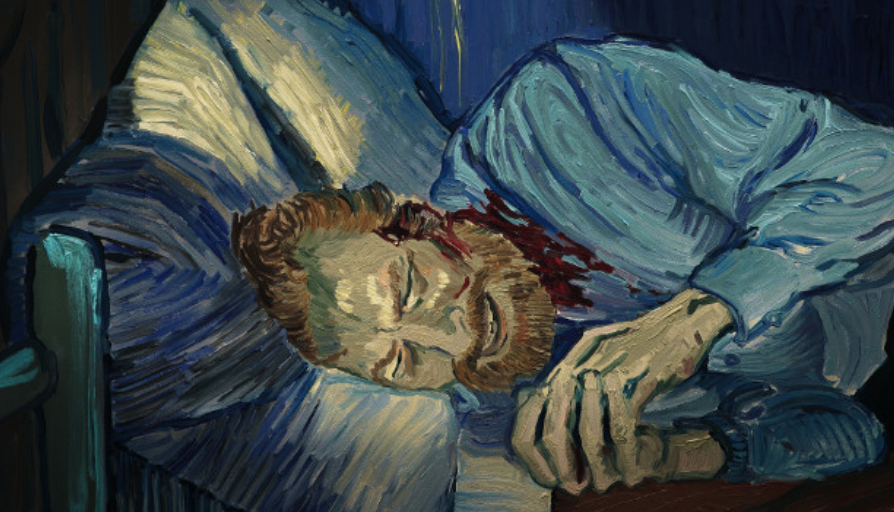

With each scene richly oil painted in a manner that makes it look as though the brushstrokes are in constant motion, the work of Van Gogh comes alive on the screen as we await to watch him die, painting to the very end in the fields of Auvers-sur-Oise. Armand, however, clings to the theory that a local hooligan, René Secretan (Marcin Sosinski), is responsible, as he was known to goad Vincent for his shyness and ineptitude with women, and was constantly waving around the very gun that Vincent ended up using to shoot himself in the stomach.

The unfathomability of such a bizarre suicide eats at Armand as he comes to grips with the extent of Vincent’s so-called madness. But there was nothing common about Vincent in life (e.g. giving his cut off ear to a prostitute as a gift), so why ought there to have been in the way he chose to experience death?

With the major takeaway from Loving Vincent being that the truest, purest artist can neither 1) have a normal life (least of all when it comes to romantic dalliances) nor 2) not somehow be a monetary drain on someone’s wallet in order to whole-heartedly pursue his medium of choice, we’re given an eye-opening view into the death of a man perhaps too sensitive and companionless to go on any longer. And maybe, somewhere deep down, Van Gogh always knew it would come to this, hence the manic prolificness of his oeuvre, turned out in a span of just eight years. For he lived and very literally died by the canvas, committed to the only thing that had ever given him a sense of purpose to the end.