With 2023 marking the year of Luc Besson being legally cleared of all sexual misconduct charges brought against him by Sand Van Roy, perhaps it’s ironic that the movie he should choose to come out with posits that, in this life, you can only trust bitches. That is to say, dogs. And sure, there are some male ones in the film, too, but nonetheless, the antithetical-to-his-denial-of-misconduct quality is there. And yet, dichotomy and duality is at the heart of Dogman, which marks Besson’s twenty-first film since he began releasing them forty-two years ago (with the short film, L’Avant-dernier, serving as his 1981 debut). And it seems with this one, Besson is determined to have it characterized as a “return to form,” which, certainly, it is. Even if a form that borrows heavily from many other recent tropes. Not least of which is Joaquin Phoenix’s performance in 2019’s Joker.

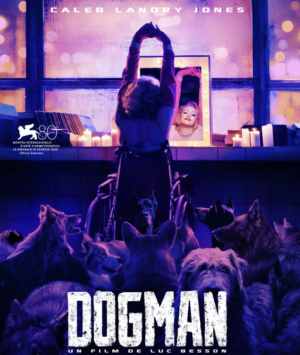

Caleb Landry Jones, who delivers the performance of his career thus far, is only too ready to emulate that trope as Douglas Munrow a.k.a. the eponymous “Dogman” himself. And yes, like Michelle Pfeiffer’s Catwoman (or even Danny DeVito’s Penguin), he gravitates toward this particular type of animal because it is the only living creature that has ever shown any type of kindness or affection toward him. This starts from an early age (as it did for Penguin with his penguins), which we learn about through the device of retelling it from the present to a psychiatrist named Evelyn (Jojo T. Gibbs). It is Evelyn who is called (in the middle of the night, of course) into the New Jersey detention center where Douglas is being held until they can decide, first and foremost, what his gender is. Initially arrested while wearing Marilyn Monroe’s “Diamonds Are A Girl’s Best Friend” getup (adding a dash of Harley Quinn in Birds of Prey into the pastiche), the police are too confused by Douglas to understand that he’s merely a cross-dresser who happened to be on his way to perform at a drag show that night before he was so rudely interrupted by someone seeking to destroy the perfectly imperfect insular world he had built with his coterie of dogs.

Naturally, we don’t get to that portion of the story until the end, after Douglas has rehashed his entire harrowing ordeal of an existence to Evelyn. Somewhat surprised that he’s so willing to talk to her (and often confess to various crimes in the process), he eventually tells her that the reason why he does is because pain recognizes pain. And for Evelyn, whose own story goes far more unexplored, that pain threatens to return in the form of her physically abusive ex-husband, who’s been skulking around her house to try to see their son, even though he’s been forbidden by a judge from doing so. But again, Besson isn’t making this movie about a Black woman. It is, as usual, the story of an alienated white man. But, at the bare minimum, Besson didn’t take the Todd Phillips approach by making him a conventionally straight incel. Granted, Douglas has his own romantic desires for a woman go unfulfilled, but it says something that he’s at home among the drag world after spending much of his youth in a cage studying women’s magazines. The ones his mother had to hide from the sight of Douglas’ violent father, Mike (Clemens Schick), behind the wall of the dog cage.

It is this cage where Douglas will be forced to make a home when Mike exiles him there. This because Douglas’ traitorous older brother, Richie (Alexander Settineri), snitches on him about feeding the dogs when they’re not supposed to be. For, in case you couldn’t guess, the only reason someone as hateful as Mike would own dogs is to use them in fights. Ergo, starving them just before one so that they’ll be extra bloodlusting. Incidentally, the word “Dogman” can also refer to a person who raises dogs for the sole purpose of dog fighting.

In a certain sense, that’s what Douglas ends up doing, too. For he raises his fellow brothers and sisters (telling his father he prefers the dogs to his own family, which is how he ends up being exiled to the cage in the first place) to fight for him. To serve as the protectors he never got in his parents—the people who are supposed to love and protect you at all costs. Instead, Douglas must receive that from the family he “makes” in his canine brethren. Retreating entirely into the pack after his father shoots a gun at him, not only clipping a finger off, but lodging a bullet in his spine that 1) can’t be removed without risk of death and 2) permanently paralyzes Douglas.

As the rest of his youth unfolds, Douglas is shuffled around, landing in a home where he meets the only woman he’ll ever love: Salma Bailey (Grace Palma). It is she who teaches him about theater, and how it is the gateway to being anything and anyone you could ever want to be. This is, undoubtedly, what affirms his love of dressing up as women, ultimately leading him to performing once a week at a drag club. But only for songs that allow him to remain stationary (he can stand without a wheelchair for the length of a song), thus performing as “old-timey” women like Edith Piaf and Marlene Dietrich (this being a very Besson touch). In the scenes leading up to Douglas’ eventual discovery of the club as a haven that will allow him to make some (legal) income, he admits to Evelyn that it was hard, at first, to find work. What with his wheelchair-bound status. This is part of what leads viewers to believe that it might have been a more discriminatory time in the U.S. (i.e., the 90s). But, to that end, perhaps the oddest aspect of Dogman is its sense of time. Although Douglas tells Evelyn he’s thirty years old, the year of his birth is shown as 1991. Theoretically, that ought to mean we’re in 2021, and yet, the use of VHS tapes for the security cameras that show his dogs stealing from rich people makes it feel like it’s meant to be set in some earlier time, when it was so much more difficult to catch a criminal (and, again, so much easier to discriminate in the workplace). But then, other details, like Evelyn talking on a cellphone with headphones while driving, continue to suggest a more current time period.

And yet, just as we don’t really question how or why his dogs can understand and react to the words Douglas is telling them, we don’t much question the holes in the fabric of Dogman’s space-time continuum. Besson is too good at delivering a filmic feast for the eyes to distract from such an anomaly. This includes using the Eurythmics “Sweet Dreams (Are Made of This)” to soundtrack Douglas’ fruitless job search before finally showing us a man in Annie Lennox drag (the suit and cropped orange hair, obviously) singing along. Eventually, Douglas finds himself in that same club where the Lennox impersonator is lip syncing and implores the owner for some work, declaring that if you can perform Shakespeare, you can perform anything.

But it isn’t just a Shakespearean or even Joker influence at play as the plot of Dogman progresses. There’s also some notable Home Alone booby trap action going on in act three, as Douglas rallies his canine army to defend him against a gang boss he enraged at the outset of the narrative. And all because he was trying to do a good deed for a sweet old lady who was being milked for too much “protection” money by these New Jersey goons. But, as it is rightly said, “No good deed goes unpunished.” Douglas has learned that time and time again, yet can continue to tolerate existence because of the purity and goodness he sees in dogs. And they, in turn, show him the loyalty and devotion he’s never found in any human. Indeed, they’ll go to the ends of the Earth to stick with their “master” (even if Douglas probably sees himself as more of an equal). In this regard, one could even bill Dogman as something like a deranged Homeward Bound. As another recent dog movie, Strays, also happens to be.

During the expectedly violent (because: Besson) denouement occurs, it’s apparent that Besson seeks to make his character Shakespearean in his fatal flaw of being a romantic, even after all he’s experienced to know better. And, because Besson loves martyr figures, he lays the Christ imagery on thick at the end, as though we needed to be reminded that Douglas most certainly possesses a bit of the Balthazar (though a donkey, not a dog) from Au Hasard Balthazar characteristic: being consistently beaten down by life despite doing no harm, yet continuing to persist in the face of his often literal bruisings. Unlike the Joker, however, this hardening of the spirit doesn’t turn him evil, per se, only makes him yet another threat to society and its insistence that “being a good boy” will get you far.

[…] Genna Rivieccio Source link […]