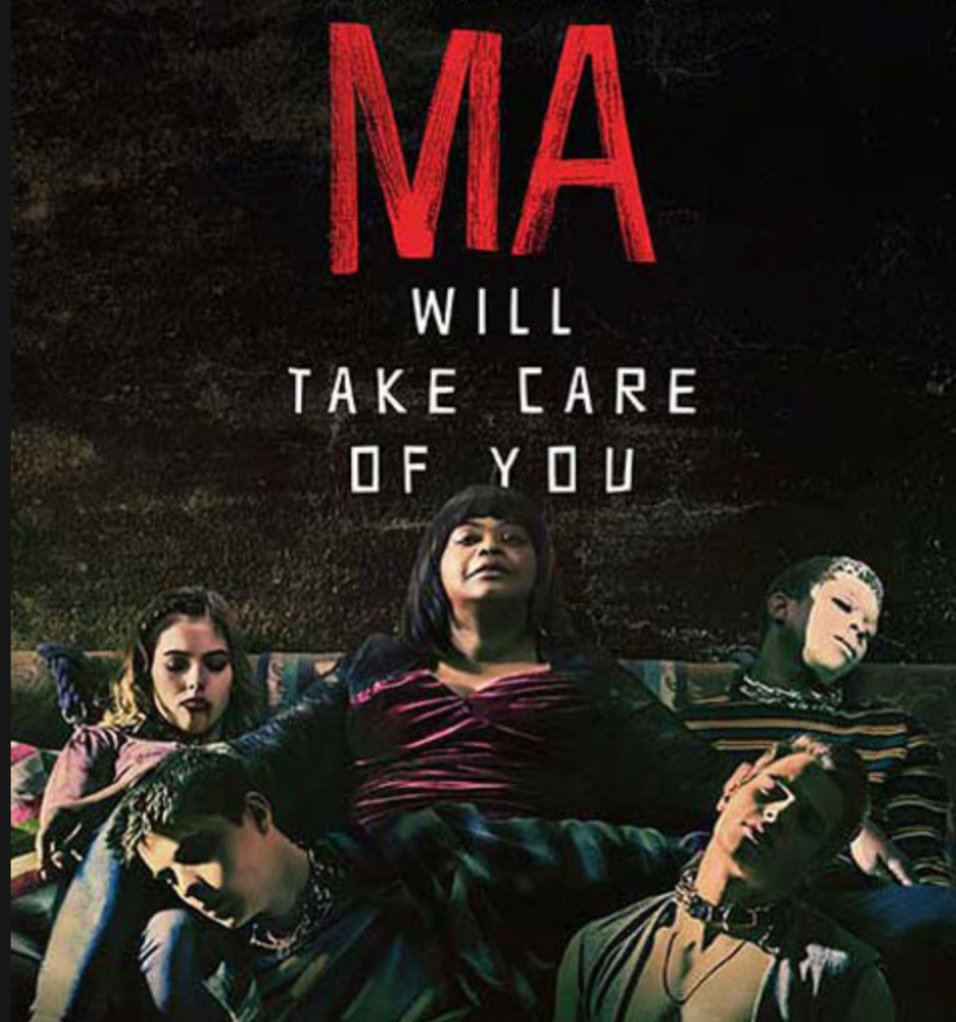

As one of the elements of bullying still largely unaddressed by the so-called bleeding hearts of primarily liberals, ostracism factors in heavily to the lifelong insecurity and mental damage of those who are deemed “not worthy” enough to participate in that sadistic ritual known as adolescence, specifically high school. For Sue Ann “Ma” Ellington (Octavia Spencer), it’s clear that wound has only augmented over time, manifesting into her bizarre need to feel a part of a new generation’s “gang” that takes shape in the form of Haley (McKaley Miller), Darrell (Dante Brown), Chaz (Gianni Paolo), Andy (Corey Fogelmanis) and Maggie (Diana Silvers). The latter has just moved into town thanks to her mother, Erica’s (Juliette Lewis), divorce from her father.

Fleeing from San Diego to start over in the place she ran from, Erica takes a job at the local casino, often leaving her absent from Maggie’s day-to-day, ergo making her the perfect candidate to fall prey to Ma’s pied piper of partying charms. It all begins innocently enough, with Maggie enlisted by her group of friends to ask Ma to buy them alcohol while they’re parked outside the liquor store. But oh how they’ve asked the wrong “amenable” adult, as Ma’s obsession with the quintet quickly escalates to Facebook stalking (do people in Gen Z even still sign up for Facebook accounts?) so as to confirm that Andy is the son of Ben Hawkins (Luke Evans), the popular quarterback type of her high school days. Flashbacks to his manipulation of her blatant crush on him slowly build to the final one in which we see just how fucked up the lengths of “youthful folly” a.k.a. cruelty can go when it comes to assuring the proverbial outsider/loser knows just how unwanted they are by the groupthink mentality that somehow rationalizes away treating someone who has done nothing wrong like total shit.

As Ma’s fetish for having parties in her basement as a place for “the cool kids” to drink the alcohol she’s providing escalates, she begins to take her need to control the fun–to puppeteer all of her unwitting props for overdue social acceptance like marionettes–to new extremes. Such as wielding the benefits of the widely available drugs at the vet clinic where she works. Well, sort of works…her constantly irritated boss, Dr. Brooks (Allison Janney) often berates her for her spaced out ways but perhaps knows that good help is hard to find, therefore doesn’t fire her. Indeed, Ma’s proneness to reveries is a testament to the ways in which daydreaming transcends into a coping mechanism when one is ostracized. But this method of coping can only put a stop to the loneliness and rejection for so long before it gives way to more extreme behavior (shit, why do you think so many kids enact the school shooting as a means to get attention after being made to feel like the outsider?).

For Ma, the desire to exact revenge for the “sins of the father,” Ben, and mother, Erica, becomes too powerful to ignore, to not take advantage of through their children. Mercedes (Missi Pyle), the fake nice popular girl, might not have a child to pay for her sins, but Ma is sure to find another way to, shall we say, take her down. As she gives more and more into her freak flag behavior (because, fuck it, everyone thinks that’s what she is anyway), a scene of her sing-muttering an ominous rendition of Debbie Deb’s “Lookout Weekend” as she cuts pictures of her pretty subjects into a revamped version of her high school yearbook cinches the case for why ostracism is the surest way to turn someone insane.

Tate Taylor, best known for directing The Help and The Girl on the Train, doesn’t ever take it quite as far as he could in interpreting Scotty Landes’ script (the most gruesome scene involving someone’s mouth being sewn shut, Catholic style), but maybe that’s not the real point of Ma–more study in just how bad bad can get when one has been rejected by the society they so desperately want to feel as though they belong to. But reject someone enough, and of course she will turn against you.

One thing that does remain in keeping with the horror genre is just how clueless the parents are to what’s going on. But when Erica finally does learn the truth about Ma’s basement parties and confronts her about furnishing her daughter with alcohol and putting her in harm’s way, all she can derangedly seethe back without shame is: “How’s it feel to be on the outside looking in?”

While critiqued for underusing Octavia Spencer’s acting ability (though if anything, it’s Juliette Lewis’ that’s underused) and playing into a certain Mammy stereotype (though that in itself seems a reductive statement), the redeeming aspect of Ma is the severity with which it addresses the long-lasting effects of being excluded. Sure, one can’t really look at it as a full-stop horror movie or even psychological thriller so much as a character study in what happens to the “loser” after high school, how that damage bleeds into the rest of their entire lives. Because no, not everyone can take their pain and turn it into money à la Bill Gates or Mark Zuckerberg.