I used to be comforted by the Madonna narrative. The one detailing her rags to riches story of rising to slow but surefire fame first locally in New York, then globally as a result of the NY stamp of approval. The one that fortified the folkloric notion that you could arrive in Times Square with thirty-five dollars in your pocket and, within the span of four-ish years, become famous. Of course, Madonna’s level of fame is of the variety achieved but once in a blue moon, particularly in New York’s already clogged sea of aspiring musicians. Going both in favor and against it at the time when she arrived in New York in 1978, there was not a wealth of females lined up at the door to become frontwomen, least of all pop stars, still a thing not invented until Madonna came along to define it.

That being said, the climate Madonna found herself in after a few aimless years spent still trying to pursue a dance career (she had dropped out of the University of Michigan, where she was studying the art), was one that forced her to put her love (of the talent) to the test of New York, an entity–not just a place–that, in her mind, was where “making it” truly mattered, as opposed to in the eyes of the collegiate powers that be. As Madonna and the Breakfast Club recounts, after a dalliance with Norris Burroughs (who would appear in the video for “Burning Up” in 1983, because Madonna has good use for all of her ex-lovers), it led her to Dan Gilroy, who Burroughs befriended after meeting him at a hand-painted t-shirt shop in the East Village. Burroughs, admitting to having the same taste in women as Gilroy, stated he wasn’t surprised that the two hit it off at the party he invited her to where he thought she might be interested to meet some other musicians and artists. As Gilroy tells it, Madonna got him into the bathroom, made some excuse about needing help to fix the clasp on her necklace and then turned around to ask, “Well aren’t you going to kiss me?” Another line that would be in character with Madonna’s persona, or at least the one she’s helped cultivate over the past thirty years in between rebranding herself as an ethereal mother of six (four adopted).

Still affecting a heavy Midwestern accent at the time (Gilroy’s recordings of their conversations certainly confirm that much), Madonna offers the calculated innocence (e.g. “crucifixes are sexy because there’s a naked man on them”) that would later appear most overtly in her 1985 TIME Magazine cover article entitled “Madonna: Why She’s Hot” for the intro to the Gilroy brothers’ take on the early struggles of M to get to the top, which began in their abandoned synagogue of an apartment in Corona, Queens (which, even now, isn’t a place where people want to live).

It was there that Madonna’s precious few moments of intimacy in NYC took place, as evidenced by her conversations with Dan, the film opening specifically with recording of her saying, “I’m awake now. Let’s go runnin’.” This simple announcement followed by an expression of desire is short but quickly describes M’s entire nature, even then: Things are on my schedule and I want this to happen now. With the recording segueing into reenactments of Madonna and Dan in bed together chatting, the danger of the half-documentary, half-narrative film is in its seeming authenticity. Yet it must be said that certain liberties are taken for the sake of explanation and not having to deal with anything too unwanted on the timeline. For instance, as the Gilroy brothers falsely tell it, Madonna came back from Paris because her “gig” with Patrick Hernandez was up at the end of the summer. In reality, she 1) didn’t want to be in a chorus line and 2) didn’t want to be molded into a “disco dolly” by his producers, wanted to be master of her own sound and career, ergo returned to New York with her tail between her legs (as much as M’s could be) to start over.

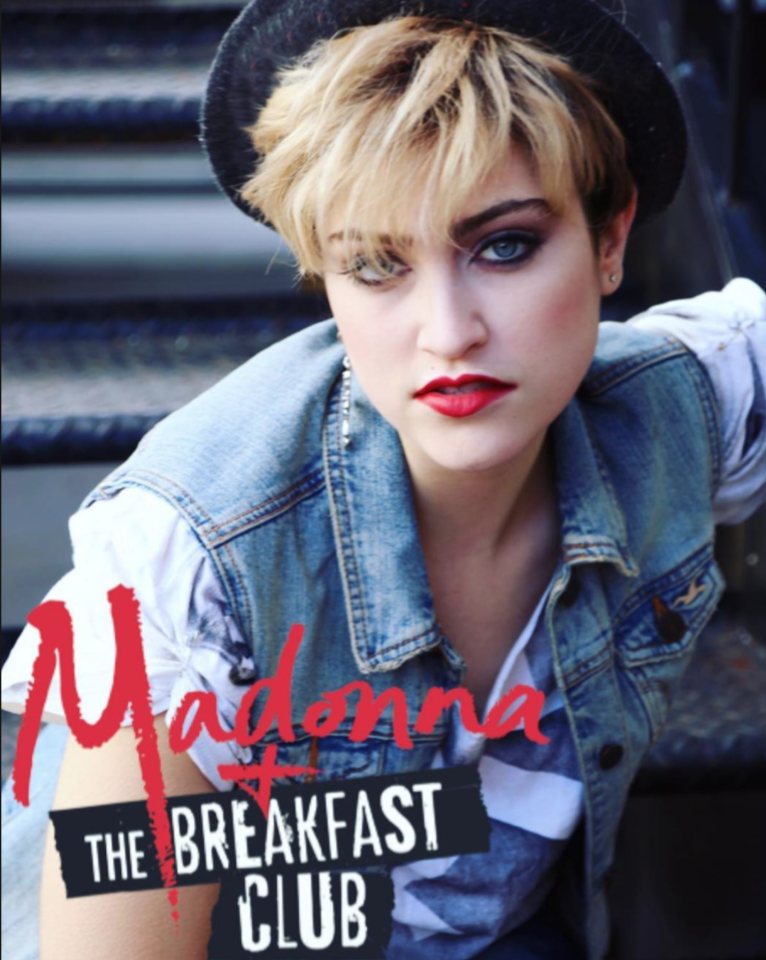

Though there are certain moments when Madonna and the Breakfast Club–clearly a labor of love–falls short in honestly (instead of white male biasedly) portraying the pop star’s ascent, the one thing it gets 100% right is casting, specifically Jamie Auld as Madonna. When hearing her tell the casting story of how writer-director Guy Guido (about as Italian-American of a name as someone can have) discovered her when she was working at Doughnut Plant, one immediately understands the kismet nature of her playing this part (and not just because Madonna, too, worked–albeit briefly–in the less bougie “donut shop” that is Dunkin’ Donuts). It’s perhaps the only touch of femininity to a background story that once at least included the likes of Pearl Lang (RIP), Whitley Setrakian (M’s college roommate at University of Michigan, but apparently only Peter Kentes could still be dug up again from that era), Erica Bell (a friend and backup dancer on her early club tours) and Camille Barbone. As for the latter, this is another subject all too cursorily broached for the sake of keeping the film about “The Breakfast Club years.” Gotham Management (renamed to “August Artists” in the movie was also located in the Music Building where Madonna and her new band (after deciding to break off with the Gilroy brothers for not letting her be in the front) shared a rehearsal space with another group of musicians. It was run by Barbone and her partner, Adam Alter. Madonna, in all her wisdom, honed in on Barbone, aware of her homosexuality and the attraction she had to what would become her star client. Or at least treated as a star, with Camille paying for M’s living expenses and even, at one point, for her to get her wisdom teeth removed.

With scenes shot in the present day iteration of the Music Building (a poster of David Lynch’s Eraserhead being a dead giveaway of that lapse in time and, more timelessly, a wheat-pasting, unfortunately, of Michael Jackson in his Jackson 5 incarnation), Auld easily gets into the character of a pushy, take no prisoners, hustling early twenties Madonna as she insists that Adam pass along her demo to Camille. In fact, watching how much she struggled to be noticed and carve out a place for herself, one wonders if it would have been harder or easier for her in the age of Instagram and YouTube, platforms which, theoretically, democratize the hustle for fame. Would her raw energy and ambition have been enough in the twenty-first century New York where everyone is flaccid as fuck with zero performing charisma (which you’ll find at any given DIY venue in Brooklyn, or what’s left of them anyway)? Or would it have made her get lost in the sea of seemingly preferred banality? Would provocateur comments like, “You know, everybody in the bible was foxy, you know what I mean? They were pretty fine” have no place in the climate of the entertainment industry’s political correctness (which still hasn’t seen fit to view Madonna with due reverence as opposed to grudging acknowledgement of being influential)?

Rather than delve into the years Camille put into grooming M to become the next Pat Benatar, Gilroy reduces it to: “And the rest of the breakups that happened she had to go off on her own–that was just the way it was.” Although the sparse amount of men interviewed (most of whom just wanted to have sex with her or did have sex with her) give her more credit than they might have in the past (in between saying things like “practicing her little songs”), it all feels boiled down to Madonna being fame-hungry, bursting with an almost off-putting eagerness to be recognized. And then, of course, attributing her musical trajectory to The Breakfast Club (a new incarnation of the band which coasted on M’s laurels after Stephen Bray produced some tracks on Like A Virgin, landing them video airplay on MTV). But Madonna was always going to achieve success regardless of who helped her along the way. In this regard, the lyrics from Evita‘s “Goodnight and Thank You” proved to be tailored to Madonna in the lines, “There is no one, no one at all/Never has been, nor ever will be a lover/Male or female/Who hasn’t an eye on/In fact they rely on/Tricks they can try on their partner/They’re hoping their lover will help them or keep them/Support them, promote them/Don’t blame them/You’re the same.”

However, at least Madonna had the attractiveness (on a side note: one has to marvel at how much older all these cronies look than she does at the moment–poverty really does age a person) and sexual energy to back up being supported by her various conquests as she stayed afloat long enough to make something come out of the blood, sweat and tears that New York extracted from her–though she was at one point low enough to consider giving it all up, going the surrender Dorothy route. Thank god or whoever she didn’t, or all we would have from the OGs of pop music would be Michael Jackson, ergo no Britney, no Ariana, etc.

One of the only new interview subjects from this period of M’s early years is Freddy Bastone, a former DJ at Danceteria who gets far too much screen time considering his insignificance in her life. This portion of the film also leaves out the tale of how Madonna kissed Mark Kamins (the DJ at Danceteria who would professionally produce “Everybody” for Sire Records once Madonna got signed) to distract him long enough to slip her demo into the tape deck. When the crowd didn’t hate it, but instead responded favorably, he let the track keep playing.

The reluctance about praising Madonna for anything beyond her looks and sheer force of will (code for promiscuity, one supposes) is what becomes most palpable as the movie goes on. “She looked like Bowie and Elvis to me” is perhaps the most directly complimentary thing said about her by Dan Gilroy.

While Madonna is consistently painted as cold and calculating on her rise to success, a man in her position doing the same thing would never be painted in the manner that she continues to be. Despite the post-#MeToo movement and the twenty-first century notion of feminism, the same story about Madonna’s early days has been told again and again. And no matter how much time passes, how “progressive” we become about women being “equal” or “viable” in the music industry, it seems that with Madonna’s incredible story, nothing changes. It’s still everyone (primarily the mostly white men she forged a flirtation or short-lived relationship with) vilifying her for doing exactly what a man would have in forging a path to fame by any means necessary.

What’s more, every time a “documentary” about Madonna comes out, the same people (especially Stephen Jon Lewicki, “director” of A Certain Sacrifice) are always dredged up to discuss what they think the knew about her: she oozed ambition and nothing–least of all emotions or personal attachments–was going to dilute that until she got what she wanted.

Putting a full-circle tilt on it, Dan and bassist Gary Burke recall Madonna visiting the set of the video for The Breakfast Club’s “Kiss and Tell.” Gilroy rehashes how she told him, “Remember how all I wanted was for people to notice me? Now I find myself just hiding most of the time.” It was a prescient assessment to set the tone for 1998’s “Drowned World/Substitute for Love,” in which she sings, “I traded fame for love without a second thought.”

It was a trade that also somewhat detracted from her original street credibility. The kind that made her a fixture in the clubs of the Lower East Side and East Village. Becoming rich and famous can quickly make one lose their edge, but Madonna has seemed to continue to exist with the memories and meaning behind those early days within her–forever coloring her “irreverent” persona. Even though she’s fled NYC (while still, of course, maintaining an Upper East Side residence there) in favor of Lisbon most recently (a city that has inspired the sound her forthcoming record), there can be no denying that learning the ropes of how to survive at one of the hardest times in the city’s history forged the icon the world has come to love (even when that love is occasionally peppered with the hate of naysayers).

Over the years, Madonna’s story has become less comforting, I’ve realized. And more of a reflection of my own inadequacies. My own inability to make the most out of my time in New York in the period known as one’s twenties when being beaten to a pulp by the city feels like a privilege rather than a constant burden. In turn, Madonna’s entire being, filled with raw energy and the unrelenting will to succeed is a tale both inspiring and dangerous. For when those who watch Madonna and the Breakfast Club (though, to be frank, you’d be more galvanized watching the VH1 Driven episode about her, the 1998 version of her Behind the Music or Madonna: Rising), are led to believe they can achieve the same goals, they might be slightly disappointed when more years pass than they bargained for and they’re still struggling to make it in an art while also focusing most of their energies on how much money is going to rent.

And yet, even more than being about Madonna’s relationship with New York and how it colored the personality that would become illustrious to all, Madonna and the Breakfast Club is about the sweetness of first real love, for that’s clearly what she had with Dan, or at least that’s what he wants us to believe as the film bittersweetly concludes with a letter from her that reads: “I never went away my sweet Danny. Love your Emmy.” And maybe she never did, for the music is what proves that much. Taking from him what she needed and moving on, as many great artists have proven to be essential to actually getting paid for their art.