In 1982, Madonna had achieved what so many who once came to New York City dreamed of: local fame in the vein of the symbolists of the nineteenth century. She was known and talked about among the most important social circles of the day–that is to say, those that orbited the downtown scene, specifically the Lower East Side and East Village. Danceteria DJ Mark Kamins was about to find out just what kind of effect her aura of self-assured illustriousness had on people when Madonna literally inserted herself into his playlist by sticking the tape of her single, “Everybody,” in the cassette player before he could refuse. As he noticed the crowd vibing to it immediately, Kamins, as the story goes, promised to get Madonna a record deal with the provision that he would get to produce “Everybody” as the first single. Incidentally, the first song (and what would become another single), “Lucky Star,” was written by Madonna with Kamins in mind–her sort of final guardian angel in at last “making it.” The lyrical content would be in direct opposition to track two, “Borderline,” in which Madonna speaks of an oppressive, stifling and unfulfilling relationship–rather like the one she shared with Reggie Lucas throughout the production of Madonna.

Though Madonna paid tribute to Lucas after his May 19th death for his contribution to enabling success at the beginning of her career with a photo and caption on her Instagram that read, “So Sad to hear that Reggie Lucas is Gone………An important part of my musical past!,” much of the production process during the creation of Madonna (released in the U.S. in July of ’83) was very tense, with Lucas leaving the tracks as is without taking into account or seeming to regard at all Madonna’s extensive critiques (would one expect it any other way, even when she was still a “nobody”?). Thus, she called in her then boyfriend (boy toy?) Jellybean Benitez to finish producing the record, with his fortuitous addition of “Holiday” making the album achieve its full potential.

Despite the fact that Madonna had hand-picked Lucas from the list of producers Warner Bros. (the parent company of Sire Records that president of said label Seymour Stein had signed her to from his hospital bed) had available to accommodate her in the studio, the rapport between the two was undoubtedly the most enfeebled of all her recording forays when assessing her simpatico relationships with subsequent, more collaborative producers like Nile Rogers, Stephen Bray, Patrick Leonard, Shep Pettibone, William Orbit, Mirwais Ahmadzaï, Stuart Price and even Avicii (RIP). In fact, much of Madonna’s longevity has stemmed from her winsome partnership with whichever producer she’s working with at the moment. Thus, in many ways, her self-titled album is extremely anomalous–not just in style and cohesion, but in the very lack of Madonna’s control over the entire project from start to finish. As she stated of the debut, “The songs were pretty weak and I went to England during the recordings so I wasn’t around… I wasn’t in control. […] I didn’t realize how crucial it was for me to break out of the disco mold before I’d already finished the album. I wish I could have got a little more variety there.” That Madonna was already slightly rueful of the record that would introduce her to the world could only be abated by the fact that she still had all that raw star quality (read: sexuality) to assure her prominence in the music world–particularly the one that was just starting to become aware of how important image was with the advent of MTV in the late summer of 1981. And wield the power of MTV Madonna did, creating videos for every single except, strangely, “Holiday.” The visual pairings for “Lucky Star,” “Borderline” and “Burning Up” would ingrain viewers’ minds for most of the early 80s until the video for “Like A Virgin” came around in 1984.

Even so, Madonna was left with a sour taste in her mouth from working with Lucas, insisting upon Benitez’s remixing of “Lucky Star,” “Burning Up” and “Physical Attraction.” It was when Benitez became a part of the project that he unearthed the rejected by Phyllis Hyman and Mary Wilson (of The Supremes, in case you don’t know) track, “Holiday,” the pièce de résistance of the entire record–the thing that ties it all together in the middle. Unlike Lucas, Benitez was of the belief that, “You wanted to help her, you know? As much as she could be a bitch, when you were in groove with her, it was very cool, very creative.” But then, Lucas wasn’t getting any bedroom action out of the collaboration.

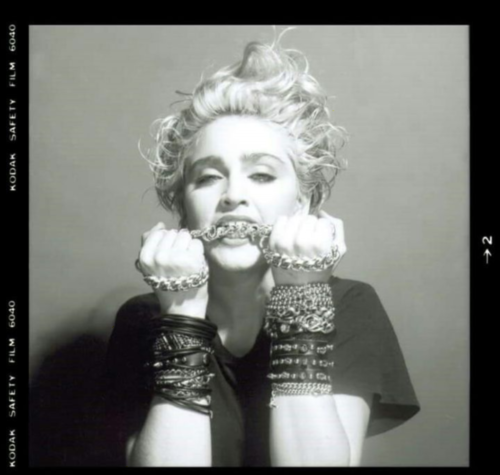

As for the now iconic photoshoot–photographed by Gary Heery and art directed by Carin Goldberg–the images of Madonna attempting desperately (yet seductively) to break out of her chains retrospectively feel like more of a metaphor for her desire for artistic freedom and expression behind the soundboards, where Lucas was all business and no pleasure. Nonetheless, he clearly “generated” a record that has endured as one of value in the evolution of modern dance pop.