While the term “yeehaw culture” (an oxymoron if ever there was one) has only recently become a “trend” (along with the phrase “yeehaw agenda”), Madonna was embodying it decades ago, with her 2000 album, Music (the vibe of which was presaged by her early 2000 cover of Don McLean’s “American Pie”). In fact, it seemed Madonna intuited George W. Bush’s presidential “win” in November months before (with Music being released on September 18th of that election year). For she had already decided on cowboy hats and other assorted “western regalia” for her first reinvention of the twenty-first century. Or rather, her photographer, Jean-Baptiste Mondino, talked her into it. The result was an instantly iconic, instantly recognizable identity from her many eras (back when people weren’t using the word “era” to describe phases of people’s careers).

And arguably the best part about Madonna’s so-called country era was that she didn’t actually try to sing country music at all. Apart from hints of it on “I Deserve It” and “Don’t Tell Me,” the latter co-written by her brother-in-law, Joe Henry. A country musician who had envisioned it as a “torch song” until Madonna decided it was much better to, like, invent the country-dance genre. Something that, of late, Beyoncé seems to think she created. Worse still, so do the legions of listeners obsessing over the “brilliant” “innovation” of Cowboy Carter. An album that, in every way—sonically and aesthetically—owes its debt to Music (just as the visuals from Renaissance do). A record that so astutely managed to anticipate the arrival of the “yeehaw president,” therefore the rise of conservatism yet again (evidently, eight years of a Democrat in the 90s meant the pendulum needed to swing the other way). Except that, in Madonna’s campy hands, those cowboy aesthetics associated with machismo and narrow-mindedness became, well, super gay. Ultra kitsch. As though Madonna was preemptively thumbing her nose at the repression and oppression that was to come with the Bush presidency. As usual, she was being ironic.

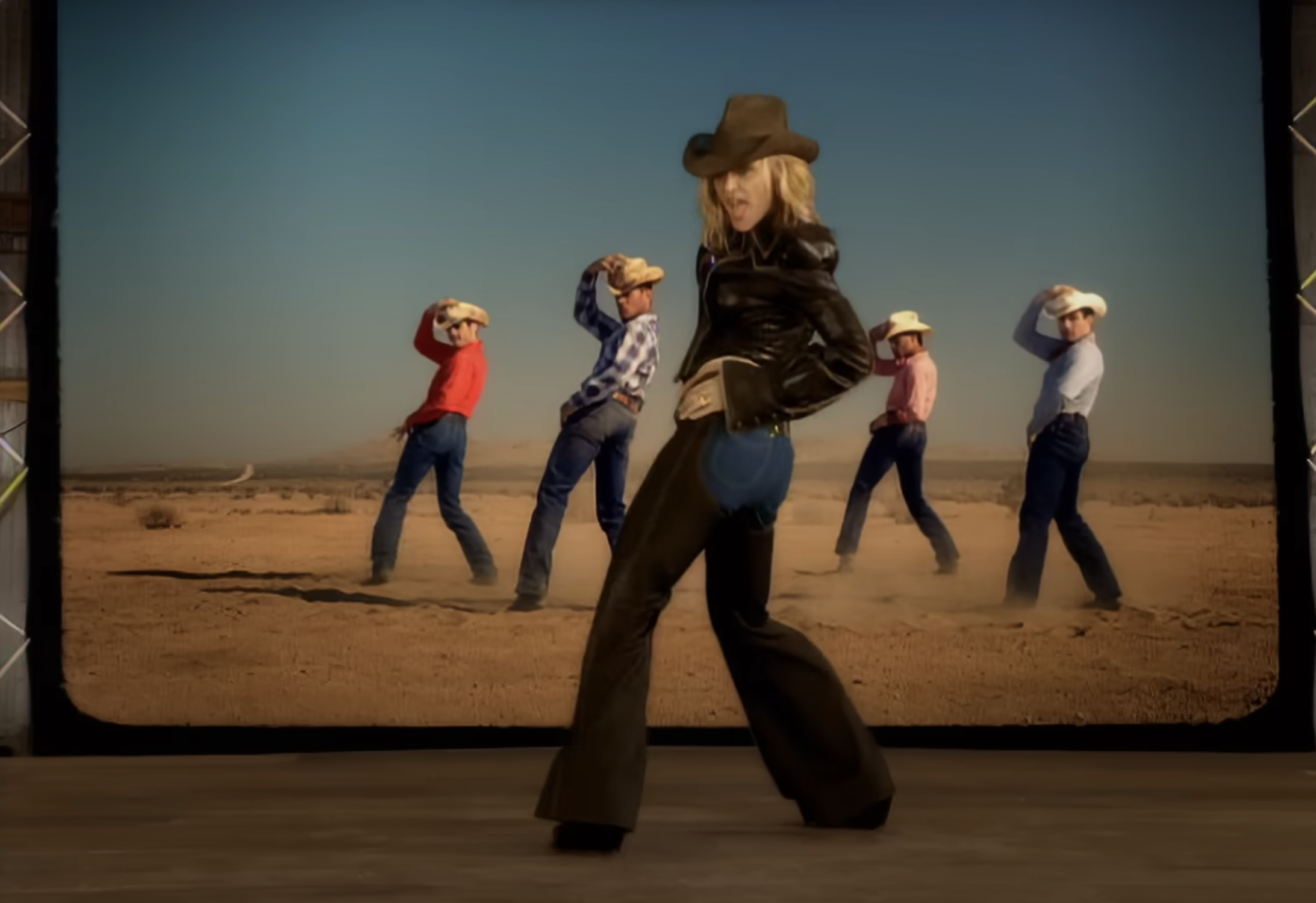

That much was made crystal clear on her album cover by pairing her “butch” denim jeans not with cowboy boots, but with ruby-red sequined high heels that riffed on Dorothy Gale’s a.k.a. Judy Garland’s famous ruby-red slippers in The Wizard of Oz. Because if anyone supports “friends of Dorothy,” it’s Madonna. And Lawd knows Dubya (and his entire administration) wasn’t going to during his two long terms in office. In this way, too, Madonna predates Beyoncé (and everyone else) in subverting/“perverting” the semiotics of western culture (a.k.a. “yeehaw culture”) in order to make it more accessible to groups (like the gays) who were typically marginalized from “participating” in it (read: being able to freely dress up in the sartorial trappings of a cowboy). One could even argue that Music was influential on spurring (no pun intended) the screen adaptation of Brokeback Mountain, released in 2005. Forever to be known as the “gay cowboy movie.” But who made it safe for cowboys to be gay five years earlier? Madonna. The Mondino-directed video for “Don’t Tell Me” solidified that fact as Madonna “bucked around” with some very fey cowboys as her backup dancers.

In fact, the only “pure archetype” of a straight cowboy is the man shown toward the end of the video, who eventually endures the humiliation of being thrown from his horse (meanwhile, Madonna relishes her seamless “ride” on a mechanical bull). After getting up from the ground, it’s obvious his pride has been wounded. And it’s also obvious that Madonna’s underlying intent is to wound the conventional straight male ego with this symbolic image. Taking it down a peg, as it were.

In addition to the album artwork and the “Don’t Tell Me” video, Madonna spent the majority of the Music promotion cycle dressed in her cowboy attire (often of a “ghetto fab” nature, like the style displayed in the video for “Music,” directed by another go-to of M’s, Jonas Åkerlund). Whether performing at the Brixton Academy or the MTV EMAs, Madonna was committed to lending a flamboyance to the conventional cowboy look that no one else before her—least of all a pop star—ever did. Here, too, one can make the case that she was even a blueprint for the fusion of pop and country that Taylor Swift would become known for by the time 2008 rolled around. And all without Madonna ever having to prostrate herself to the genre of country at all. In this regard, too, she set a new precedent for solely culling the images of western/country/Americana without feeling the need to back it up with some claim of “deserving” to wield this imagery (e.g., the way Beyoncé and her supporters keep being sure to tout how she’s from Houston and spent her childhood at rodeos).

Granted, Madonna has far more working-class roots than most of the people who have dabbled in country of late, with her salt-of-the-earth Midwestern background also being an indication of “country-ness” beyond the South. But needing to insist she was “worthy” of being deemed country was never part of her game plan for Music. Instead, she wanted to play up the idea that artifice is a key aspect of the personas people try on. Even “real” cowboys who, sooner or later, have to take off their costume at the end of the day. The “Don’t Tell Me” video amplifies this concept of western culture and lore being a construct by briefly deceiving the viewer into thinking Madonna is walking on a real deserted road in the heart of the West before Mondino pans back to reveal that it’s nothing more than a screen projecting the image while Madonna walks in front of it.

Unlike the proponents of “yeehaw culture” in the present, Madonna never felt obliged to make some grand claim about her “legitimacy” as a “country western star.” The point, instead, was to lightly poke fun at the hyper-masculinity of the “culture” and put her own feminine (/homo) stamp on it. Alas, it seems many people have quickly forgotten her major contribution to the mainstream-ification of cowboy chic. In such a way that she did make it safe for non-white male conservatives to want to partake of it. Though not everyone might be thanking her for making this style extend beyond the backwater roads of the West, Midwest and South.