“I’m glad he doesn’t own a petrol station, you know? I’m glad he’s not a doctor.” So says a young M.I.A., rattling off potential stereotypes of her father, Arul Pragasam, a Sri Lankan revolutionary, key Tamil activist and founder of the militant group EROS (Eelam Revolutionary Organisation of Students), which would later become absorbed by the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam. And it’s true, M.I.A. would likely not be the iconoclast she is today without the example of her rebellious father (presented to her as her uncle for a considerable portion of her preadolescence for the safety of the family). With the constant upheaval that came with being the daughter of a revolutionary–in addition to the general chaos of the Sri Lanka Civil War at the time–M.I.A. left her semi-native land (she was born in London before her father brought them back to Jaffna when she was six months old) at the age of nine with her mother, Kala, a seamstress who struggled to make ends meet as she raised her three children during Arular’s–which he had changed his name to by this point–French leave (or, in this case, Sri Lankan leave).

In terms of having a sense of belonging, it wasn’t much better for M.I.A.–still Mathangi “Maya” Arulpragasam at the time–in southwest London, specifically the housing project known as Phipps Bridge Estate in the Mitcham district where she was just one of two Asian families living on the estate.

Beginning with visual arts and then documentary film as she began her years at Central Saint Martins (Jarvis Cocker was most definitely not referring to her rare breed type at that school in “Common People”), the jump to music was inevitable–and it was with her background that she was able to pull together all the elements for album artwork and music videos that made her such an instantaneous success using, what else, MySpace (even before Lily Allen rode that gravy train in 2005, M.I.A. forged the path for literal overnight fame in ’02). Unconventional means of ascension were, after all, nothing M.I.A. hadn’t already mastered. It was, in fact, how she managed to get into St. Martins, explaining to Arthur Magazine, “I didn’t have grades to get into St. Martin’s; I just totally emotionally blackmailed the head of the Art Department, told him that I’d be a hooker if they said no, and they let me in…He said I’ve got chutzpah, and maybe the person to change something about their institution was someone who had chutzpah, because everyone else conformed and filled out the application form six times to get into an institution that was supposed to teach people about becoming unconventional. He thought that compared to how everyone else got in there, I was what the institution needed.” Yes, that was and is for certain, the institution extending to mean something more global after St. Martins.

Explaining that one of her ways of coping through the turmoil of her existence during a period when she was forced to finally sit still for a solid year with her thoughts–at the insistence of Elastica’s Justine Frischmann–she finally gave the process enough time to pour out, commenting, “That’s when I started borrowing the four-track and having a go. I got really obsessed with it, more than art, film or anything. I became an information junkie. I’d go for days without brushing teeth, feeling like I’m learning so much, getting up at eight in the morning and on the four-track all day. Lost all my friends, wouldn’t comb my hair for days, just stick on my sweatshirt and have a go.”

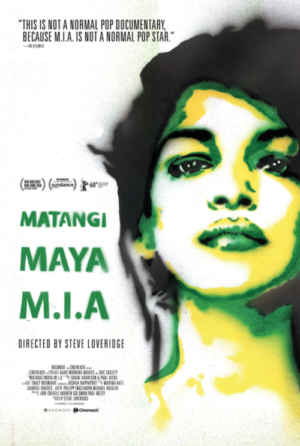

Strangely, friend and director Steve Loveridge’s four year absence from communicating regularly with M.I.A. to put together this film was something tantamount to M.I.A.’s own fascination with creating songs during that period–but did not mean he wasn’t living and breathing her and her origin story every day as he compiled the narrative direction and theme of the documentary, which M.I.A. had believed would simply be another “on the road” sort of rockumentary as opposed to an in-depth delving into the past that shaped such a unique and inimitable sound. One that was, though not addressed in Matangi/Maya/M.I.A., heavily encouraged by Peaches, who served as the opening act for Elastica during their final tour in 2000.

But even before these two women, there was the pinnacle of the strong female role model (which M.I.A. would later express some disappointment in after the Super Bowl): Madonna. With her early years spent listening to M on her headphones (and seeing her during those rare moments of access to the telly) before her radio was stolen, M.I.A. then heard the hip hop basslines of the likes of Public Enemy thanks to her neighbors blasting it from their windows. All the influences were coming together in the blender that would spit out M.I.A.’s unprecedented amalgam of sounds. All it took was a return to her homeland in 2001, wanting to make a film of some kind about Sri Lanka, that would cement the sounds in her mind.

It wasn’t just Frischmann and Peaches that were useful to M.I.A.’s germinal stages of music creation. There was also Diplo, who she met in 2003 at the Fabric nightclub in Farringdon. Though, of course, the two were already somewhat familiar with one another’s work through XL Recordings, eventually leading Diplo to produce Piracy Funds Terrorism as the two commenced an adversarial romance naturally not addressed in the documentary (though it would have been a pertinent plot point in speaking to the constant misogyny M.I.A. has come up against in her so-called outspokenness–most notably in her dealings with the NFL in response to her middle finger flashing during the 2012 Halftime Show in which Madonna featured her for the live performance of “Give Me All Your Luvin'”).

Through all of the “controversy,” which only augmented the richer and more powerful (therefore more dismissed as a hypocrite) she became, “the immigrant experience” was not something she could let go of in any form of her work–for it is a constant exploration of place, and of realizing that the best things happen when we show up to places where we “shouldn’t be” (which somewhat conjures some of the interludes from Janet Mock on Blood Orange’s Negro Swan).

Though probably not quite as surprised as she was by the condescension of her New York Times Magazine profile, crafted by Lynn Hirschberg to make her look like a bourgeois asshole, M.I.A. was more than somewhat jarred by the final result of the footage Loveridge put together, noting, “[He] took all the shows where I look good and tossed it in the bin. Eventually, if you squash all the music together from the film, it makes for about four minutes. I didn’t know that my music wouldn’t really be a part of this. I find that to be a little hard, because that is my life.” Yet one could argue that the documentary is only about the music–because you can’t fathom M.I.A’s beats and lyrics without grasping her origins. And as for her life–all about the music, as she iterated above–it is a good one, one that fulfills her grandmother’s advice to “live a happy life”–even if that often times means having to deal with literalists and consumerist twats that simply cannot and do not want to see beyond the surface.

For those who feel M.I.A. is repetitive in her message, whether in lyrics or interviews, what it boils down to is, “Sometimes I repeat my story again and again because it’s interesting to see how many times it gets edited, and how much the right to tell your story doesn’t exist. People reckon that I need a political degree in order to go, ‘My school got bombed and I remember it cos I was 10-years-old.’ I think if there is an issue of people who, having had first hand experiences, are not being able to recount that – because there is laws or government restrictions or censorship or the removal of an individual story in a political situation–then that’s what I’ll keep saying and sticking up for, cos I think that’s the most dangerous thing. I think removing individual voices and not letting people just go, ‘This happened to me’ is really dangerous. That’s what was happening… nobody handed them the microphone to say ‘This is happening and I don’t like it.'” But now, you couldn’t pry M.I.A.’s microphone out of her cold, dead hands if you tried (even if she does claim AIM was her last record). What’s more Matangi/Maya/M.I.A. immortalizes a story she no longer has to repeat to achieve credibility.