There was a time in the 90s where it seemed one couldn’t avoid a tabloid (whether in print or TV) headline about a teacher’s “inappropriate relationship” with a student. This overt euphemism, of course, meant that a sexual line had been crossed and an irrevocable trauma incurred (regardless of the protests of the student in question who insisted they “wanted it”). More often than not, these headlines seemed to be about women abusing their power as an authority figure. This would later feel like something of a conspiracy when taking into account that men in such authoritative roles, including teachers, had long been known to abuse that power. This being accepted simply as “the way of the world.” But the media choosing to home in on female teachers pursuing their male students like predators with prey seemed especially pointed during a decade when the highest office in the land, the President of the United States, was gleefully exploiting the trappings of his own influence. Many times over, mind you—not just just with Monica. Of course, Bill Clinton at least had the “decency” to hunt for women who were over the age of eighteen (the ones we know about anyway).

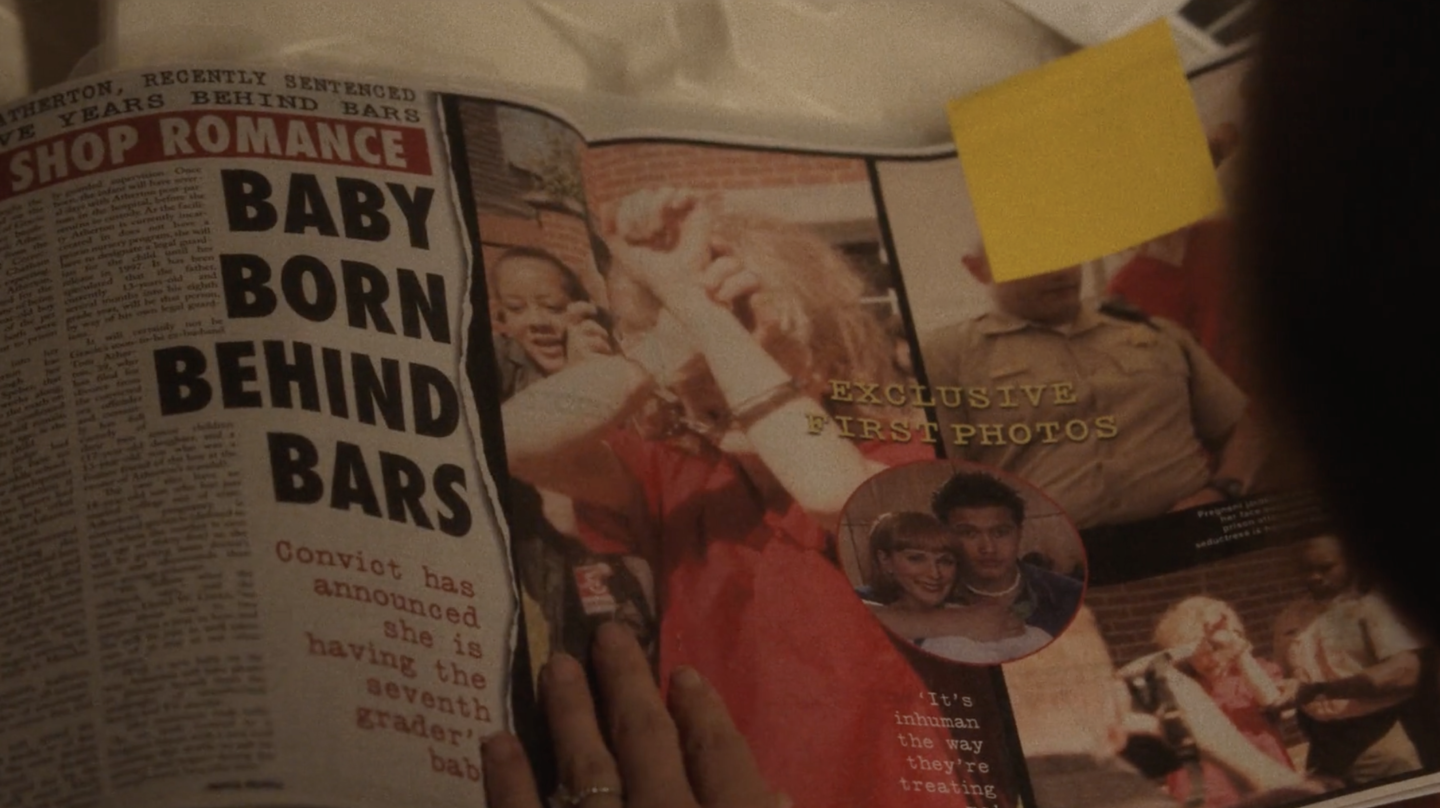

The most infamous example of that teacher-student trope initially came to light in 1996, when an elementary school teacher named Mary Kay Letourneau was caught by police in a sexual act with one of her students, twelve-year-old Vili Fualaau, in her car while parked at a marina in Burien, Washington. “The scene of the crime,” as it were, where she taught at Shorewood Elementary School. It wasn’t until 1997, however, that a relative of Letourneau’s husband, Steve, reported Mary Kay’s behavior to the police after they had already turned her loose in the summer of ‘96. That same year, Todd Haynes would have been thirty-six (not at all far from Letourneau’s age when she was “exposed”) and would have just come off the high of releasing his sophomore film, Safe—also starring Julianne Moore. There’s no doubt that the headlines swirling around Letourneau were on Haynes’ radar as much as anyone else’s. And perhaps he knew that it would be best to file the story away for some later date—after the “made-for-TV movie period,” which had its biggest peak in 2000, when both Unauthorized: The Mary Kay Letourneau Story and Mary Kay Letourneau: All American Girl hit the airwaves.

Releasing a film loosely based on Letourneau in 2023 might, to some, seem “irrelevant,” however Haynes’ decision to make the movie now actually feels timelier than ever. For the culture has only become more obsessed with involving itself in the trauma of others by both sensationalizing and constantly analyzing it. While many are quick to point out that the tabloid culture/frenzy that thrived from the late 80s to 00s is now “a thing of the past,” it seems those people are the ones who fail to make the correlation between that and the sudden obsession with true crime stories (this being a key word choice for the audience to distance itself from any culpability in causing the perpetual “recycling” of a real person’s trauma). The salivation over that kind of genuine trauma that ruined someone else’s life now serving as “pure entertainment” for the masses. And yes, the tale of Mary Kay Letourneau is very much a true crime story as well. One that, in the end, wasn’t treated like a crime, so much as “every boy’s fantasy come true.” May December seeks to obliterate the idea that scratching the “hot for teacher” itch is something to be proud of. Joe Yoo (Charles Melton), the filmic representation of Fualaau, is a prime example of that as he exhibits a state of eternal arrested development despite himself being a father to two children going off to college.

It is amid this backdrop that a TV actress named Elizabeth (Natalie Portman, channeling her Black Swan character in search of perfection vibe) shows up to their seemingly “idyllic” world. With Haynes trading the setting of suburban Washington for sweltering Savannah, Georgia (and the student-teacher dynamic for an employer-employee one). The opening to the film, though, keeps that setting vague, showing us faint impressions of plants with a monarch butterfly occasionally appearing on one of them. The symbol of the butterfly will, of course, be both important and recurring throughout the narrative as Haynes emphasizes the point that Joe was never allowed to emerge from his own chrysalis after being effectively suffocated by Gracie Atherton (Julianne Moore) and his imbalanced relationship with her. It is during this overture with the monarch resting on select plants that the dramatic theme music from Marcelo Zarvos (who basically repurposed Michel Legrand’s theme for 1971’s The Go-Between) plays into the concept of melodrama, and how our society feeds off it—especially when it’s prepackaged in such a way as this. A “ready-made” soap opera that “writes itself” because the story really happened. That Haynes chose to bring back the long-ago extinct overture portion of a movie also plays into a notion that Adrienne Bernhard of The Atlantic addressed when remarking, “Given no option but to sit and wait, audiences quickly grow restless. But the film overture is in fact a respite from distraction, even as it’s an occasion for distractibility. These opening sequences offer the chance to rediscover music as a kind of cinematic storytelling, to think about the ways form dictates content, or to simply reflect. For moviegoers, the overture is a bridge between real life and the story they’re about to enter…” This last sentiment being key to how Haynes and casting director-turned-screenwriter Samy Burch want the viewer to understand that there is a bridge between real life and dramatization, though “mass culture gobblers” rarely seem to comprehend that there is a distinction. Simply “hungry for more drama” without realizing that there are actual people who suffered through the “story” that has been rendered into stylized “entertainment.”

The most heart-wrenching (yet still meta-ly dramatized) example of this in May December arrives after Joe predictably (indeed, that predictability is part of the “soap opera drama” audiences are addicted to) ends up sleeping with Elizabeth, whose own morbid fascination with the story and how to best “inhabit” Gracie mirrors the public’s unhealthy interest in cases like these. Or “stories,” as they’re billed. This word encapsulating a form of distancing language that helps alleviate “audiences” of any potential guilty conscience about treating the horror that happened to somebody like Joe (or Vili) as something for “consumption.”

So when Elizabeth, during their post-coital powwow, starts to tell him, “You’re gonna do what you’re gonna do but…stories like these—” Joe angrily interrupts, “Stories? Stories?” Suddenly, he can see that Elizabeth is treating him like a “curiosity” just as everyone else has…even (and especially) Gracie. Elizabeth tries to soothe, “You know what I mean…instances. Severely traumatic beginnings.” Joe shouts, “This isn’t a story! This is my fucking life!” Feeling once again used because he thought they “had a connection” that would make it worth cheating on Gracie, he asks, “What was this about?” “This is just what grown-ups do,” she informs him with an air of condescension. In other words, she’s digging the knife in about how naïve he still is, even after all these years. Because Gracie has all but assured his perennial arrested development, treating him like her oldest son when she chides him for drinking too much or cuts him a piece of cake for him to taste so he can praise her for its goodness.

And as for that abovementioned word, “naïve,” Gracie swears up and down that’s what she is, too. Telling Elizabeth coldly in the bathroom of the restaurant where they’re celebrating her twins’ graduation, “I am naïve. I always have been. In a way, it’s been a gift.” So it is that she offers a dual meaning for that statement. On the one hand, her so-called “innocence” is what attracted her to a child in the first place and, on the other, it’s her defense mechanism for blocking out any sense of wrongdoing about her actions regarding Joe. As Elizabeth puts it to her presumed boyfriend or husband over the phone, “She doesn’t seem to carry around any shame or guilt.” The man’s response is, “Yeah, that’s probably a personality disorder.” And yes, Letourneau, at the bare minimum, did have bipolar disorder. Perhaps even anosognosia, based on her intense denial of how fucked up the situation was.

The hyper-stylization that Haynes’ is known for comes in quite handy for a movie like this, which seeks to make the viewer aware of that stylization for “entertainment purposes.” One of the most glaring instances of this happens at the five-minute mark of the movie, when Gracie opens the refrigerator and Zarvos’ already signature score starts booming over the innocuous scene as a rapid zoom-in on the side of Gracie’s face occurs. The music then dies down as she says calmly, “I don’t think we have enough hot dogs.” There’s something altogether Twin Peaks-ian about it. So odd and bizarre on the surface, yet clearly intended to make the viewer hyper-aware of their participation in Hollywood’s need to play up melodrama in films “based on a true story”—that infamous disclaimer being known for automatically luring people in with even more piqued interest.

But while the Mary Kay Letourneau “story” has so often been focused primarily on her, May December refocuses the lens on the victim in a scenario such as this by highlighting the fact that it’s a clear-cut case of grooming. Not some “fantasy fulfilled” trope that is so often reiterated in pop culture, particularly when it comes to the male student “getting to” have sex with his teacher. Among such glorifying examples being Frank Buffay Jr. (Giovanni Ribisi) and Alice Knight (Debra Jo Rupp) on Friends, Pacey Witter (Joshua Jackson) and Tamara Jacobs (Leann Hunley) on Dawson’s Creek and Donny Berger (Adam Sandler) and Mary McGarricle (Eva Amurri) in That’s My Boy. Then there was Norm Macdonald on Saturday Night Live’s “Weekend Update” quipping at the time, “In Washington State, elementary school teacher Mary Kay Letourneau pleaded guilty to having sex with a sixth-grade student… Miss Letourneau has been branded a sex offender, or as the kids refer to her, ‘The greatest teacher of all time.’” All pop culture “moments” that sought to reinforce the concept that a teenage boy is 1) “lucky” to find himself in such a scenario and 2) capable of “seduction”—of being “in charge” of the situation when, in fact, it’s always the responsibility of the adult to know better. To not allow a child like Joe to say, “Gracie didn’t take my childhood. I gave it away”—this being a caption from one of the old tabloids Elizabeth is going through for “research” (read: once again, morbid fascination).

Meanwhile, Joe seems to be doing his own “research” on Elizabeth, repeatedly watching her “performance” in an obviously sexual face wash commercial reminiscent of those late 90s/00s Neutrogena ads starring celebrities like Jennifer Love Hewitt and Mischa Barton splashing their face with water while acting as though it wasn’t sexual at all. Between this and his constant texting to another woman (/fellow monarch enthusiast), it’s clear Joe is having plenty of second thoughts about his marriage and life in general as he realizes that, without his children around as a buffer, he’s going to have to face a far more undiluted truth about the nature of his relationship with Gracie. That includes coming out of denial with continued statements such as, “People, they, like, see me as, like, a victim or something. I mean, we’ve been together for almost twenty-four years now. Like, why would we do that if we weren’t happy?”

The answer he can’t acknowledge, of course, is that he was manipulated into being her “boy toy” at such a formative age that he can’t imagine her as the villain. As someone who could do harm—irreparable damage—to him. The reason they would “do that” if they weren’t happy, therefore, is not only because they both risked so much for that state of togetherness, but because Joe was effectively brainwashed by Gracie. This is part of why his underlying worry for his own son, Charlie (Gabriel Chung), bubbles to the surface after the two get high together, with this marking Joe’s first time doing so (yet another indication of his enduring innocence). On the verge of tears, he tells Charlie that “bad things happen.” When Charlie tells him not to worry about him, Joe replies, “It’s all I do.” After all, who knows better than Joe what kind of wolves in sheep’s clothing exist out there?

Nonetheless, he can’t seem to see Elizabeth for what she is either: another sicko. Grossly obsessed with the “freakshow” element of Joe and Gracie, and freely admitting so as she rolls up to their daughter Mary’s (Elizabeth Yu) drama class and tells the students, “I wanna find a character that’s difficult to, to, on the surface, understand. I want…I want to take the person, I want to figure out why are they like this. Were they born, or were they made?… It’s the complexity, it’s the moral gray areas that are interesting, right?” Getting true insight into why Elizabeth wants to play her mother, Mary storms off in a huff after being dropped off at home by the actress. As for discovering “why” Gracie is “like this,” Elizabeth briefly thinks she has it when Georgie (Cory Michael Smith), a son from Gracie’s marriage to Steve, tells her that Gracie was sexually abused by her brothers starting when she was twelve. This detail is particularly relevant when considering that, per most studies, female sex offenders not only tend to be both white and in their thirties, but also victims of sexual abuse themselves. Ergo, the old chestnut, “Hurt people hurt people.” It also bears noting that Letourneau’s childhood friend, Michelle Lobdell, would find out that Mary Kay was, indeed, sexually abused as a kid. Then there was the matter of her father, the ultra-right-wing politician John G. Schmitz, having an extramarital affair that was exposed when he admitted to fathering his paramour’s children. That woman, Carla Stuckle, also happened to be a former student of Schmitz’s. As it is said, the apple doesn’t fall far from the tree.

Nor does Gracie’s character from Mary Kay’s actual “personage.” Both telling themselves whatever they need to in order to keep living the lie that their romance with a preteen was just another case of “forbidden love” à la Romeo and Juliet (cue the “Who was the boss?” line that was clearly repurposed from an interview Fualaau and Letourneau gave in 2018 for Australia’s Sunday Night). In some ways, Elizabeth finds that “refreshing.” The ability to wake up every day as though you’re a blank slate with no past indiscretions to pay for in the present. As though there was no collateral damage in the fallout of such reckless decision-making. As for Georgie blaming his mother’s psychoticness on her childhood, when Gracie tells Elizabeth that what Georgie told her about her brothers is a lie (the implication being, ultimately, that it wasn’t), she muses, “Insecure people are very dangerous, aren’t they? I’m secure. Make sure you put that in [the movie].” This type of arrogance on Gracie’s part (the type that leads to her insisting she was the one seduced by a twelve-year-old), of course, is the very epitome of why overly secure people (read: narcissists) are just as dangerous as your insecure Hitler and Napoleon breeds.

Left standing in the middle of the grass at the graduation, the final minutes of May Decemeber show Elizabeth repeating the same scene in the pet shop where Gracie and Joe first began their “romance.” None too subtly holding a snake in her hand, Elizabeth-as-Gracie turns to the actor playing Joe and asks, “Are you scared? It’s okay to be scared.” “I’m not,” he says. Elizabeth-as-Gracie: “She doesn’t bite.” Actor-as-Joe: “How do you know?” Elizabeth-as-Gracie: “She’s not that kind of snake.” No, instead she’s the kind of snake who ingratiates herself gradually toward her prey.

The scene is filmed a couple more times, with Elizabeth begging for another take as she says, “Please… It’s getting more real.” That fixation on “authenticity” all done in service of, in actuality, lending a total sense of unreality to the event in question. Which makes it even easier for the masses to digest. So for anyone asking: why dredge up this “story” again now? Well, the unfortunate truth is, it’s more pertinent to the culture than ever.

[…] Genna Rivieccio Source link […]