In a series called Mondo Bullshittio, let’s talk about some of the most glaring hypocrisies and faux pas in pop culture… and all that it affects.

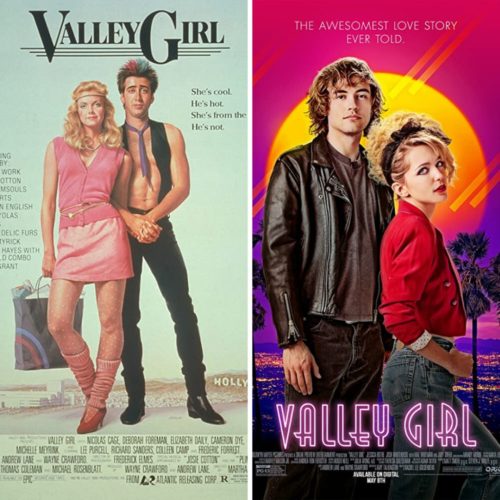

Unquestionably, every movie Nicolas Cage put out in the 80s was solid gold (among said treasures being Peggy Sue Got Married, Raising Arizona, Moonstruck and Vampire’s Kiss). But the most shining of them all was 1983’s Valley Girl. Directed by Martha Coolidge (yes, distantly related to Calvin), the co-writers of the “forbidden love” narrative, Wayne Crawford and Andrew Lane, had loosely based it on Romeo and Juliet. And indeed, in the 80s in Los Angeles, there was perhaps no bigger cultural and socioeconomic divide than the one between denizens of Hollywood and denizens of the Valley (a.k.a. San Fernando Valley for those who haven’t already been indoctrinated to Los Angeles parlance and geography).

On the Valley side of the partition is Julie Richman (Deborah Foreman)–whose name says it all with both a nod to Shakespeare and her affluence factor. Popular and unconcerned with much beyond going to the Sherman Oaks Galleria with her friends and charging their credit cards (complete with old school credit card machine, and one purchase topping out at $192.95 during an excursion into a single store), Julie only starts to question the banality of her superficial existence when she encounters Randy (Cage) at a party he crashes with his best friend, Fred (Cameron Dye), a fellow piece of “Hollywood trash” that figures prowling around a Valley party might yield some sort of “babe” potential. And it does, at least for Randy, who shares the sort of “love at first sight” glance with Julie that can only exist within the frames of cinematic glory.

As Julie has freshly broken up with meathead jock, Tommy (Michael Bowen), who, unbeknownst to Julie, cheated on her with her friend, Loryn (Elizabeth Daily), she falls fast and hard for the “alien” ways of a guy like Randy. In comparison to the “Val dudes,” he’s sensitive, unique and interesting. But alas, no honeymoon period can last, not even in the fairy tale tableau of Los Angeles, and the inherent chasm between them starts to augment beyond repair.

With an opening soundtracked to Bonnie Hayes’ “Girls Like Me,” the story immediately establishes that the Valley girl is both aware and blissfully unaware of her ridiculousness as the lyrics admit, “They got a word for girls like me/They’ve got a name, but they don’t wanna use it/It’s all the same to girls like me/It’s all or nothing to girls like me.” And all or nothing, to Julie, means either being with Randy and giving up her vapid friends or taking Tommy back and securing her favor among “her own kind” anew. As shallow and insecure as all teenagers are, Valley girls or not, she naturally chooses the latter option.

In the 2020 version, it appears as though Alicia Silverstone is supposed to serve as the aged Julie of the ensemble, making it a vague sequel–and also a musical, because the best way it would seem, in the opinion of modern filmmakers, to make the 80s palatable to modern audiences is to really layer on the cheese thickly (the same way 2011’s Take Me Home Tonight did) for “ironic” cachet. Therefore, in the trailer, she tells her recently broken up with daughter that she knows just how she feels, going into a flashback mode that prompts her daughter to interrupt, “Stop. You were singing and dancing on a fountain?” in reference to Julie dancing about the mall with her friends. Silverstone shrugs, “That’s how I remember it.” So re-commences the flashback, soundtracked to another remake… of The Go-Go’s “We Got the Beat.” And, naturally, we seem to be in 1984, instead of 1983, when the original came out, for our lead, Jessica Rothe (of Happy Death Day fame) is bedecked in Madonna’s “Like A Virgin” regalia as she encounters Randy (Josh Whitehouse) at a party in a bigger, better iteration of the original house. That so-called “bigger and betterness” contributing to the general ersatz 80s feeling (mostly pertaining to excess), which also failed in 2008’s The Informers, an adaptation of Bret Easton Ellis’ L.A.-based short stories.

Here, too, the forced fakery of it all is patent in the movie’s trailer alone, which does not bode well for the overall effect the full-length feature will inflict. One that only serves as an inevitable insult to the original masterpiece of 80s teen cinema. For Valley Girl is not only untouchable overall, but also something that can’t be “updated” in a time like now, least of all when concepts such as “love” and materialism come across as more anachronistic than ever.