There is a joke made in season one of Flack when addict/publicist Robyn (Anna Paquin) is trying to come up with ways to make her seventeen-year-old pop star client be seen as no longer “a little girl.” She offers the notion of a lesbian sex tape, saying, “It’s well-shot, intended for private use, grown-up, sophisticated—think Madonna.” Her friend and colleague, Eve (Lydia Wilson), chimes in, “Old Madonna, not old Madonna.” Yes, there is this idea that old a.k.a. vintage Madonna products are the superior ones to both behold and listen to. Particularly as Old Madonna is not “sightly enough” to be appreciated, which bleeds into her musical output as well. The vintage, “sophisticated” era Robyn and Eve might be thinking of could range anywhere from the leaked nude photos that were published in 1985 editions of Playboy and Penthouse to the controversy of the 1990 “Justify My Love” video to the “pantomimed” masturbation during “Like A Virgin” at the Blond Ambition Tour to the trifecta release of the Sex book, the Erotica album and Body of Evidence in 1992. Whatever the case, it’s safe to say that the best bifurcation point between “old” and “new” Madonna presently stands at the dividing line between before and after the year 2000.

Signaling an entirely different century from the one Madonna came up in—and the one she made mass media her bitch in—it also meant the Queen of Pop was going to need to dig deeper into her bag of tricks to “stay relevant.” Luckily, the 00s were still a carefree time largely absent of pervasive social media usage (even if that meant, in exchange, tabloid supremacy of the kind that ceaselessly tortured Britney Spears). This meant Madonna had some time to find her footing before something like “the bottom” dropped out (e.g. her often lambasted Instagram posts criticized for tone deafness). And in doing so, she came up with Music, a record that sounded like nothing else that was coming out at the time, in large part thanks to the help of producer Mirwais Ahmadzaï. Its electronic rhythms felt tailor-made for what was supposed to be a “futuristic” century—that is, before we came to find just how ghetto it would turn out to be (and no, we’re not talking “ghetto fab” like Madonna’s image in the video for “Music”).

While maintaining her own among the rise of “pop tartlets” Britney and Christina, she further wielded the zygotes to her actual advantage by treating them as her own little marionettes at a now immortal 2003 VMAs performance of “Like A Virgin” and “Hollywood.” This came on the heels of everyone being ready to write off American Life, her ninth studio album, as her first real flop. Where Erotica had been commercially unsuccessful because it hadn’t made it to the number one album position, American Life actually did chart at that level, but was still panned by critics for its sonic choices (particularly the illustrious “American Life” rap and Madonna generally getting too friendly with the vocoder on songs like “I’m So Stupid”). Her message of shunning the trappings of fame and acknowledging its meaninglessness rang hollow to most, who still saw her as the most fame-hungry of all. Whatever one’s view, it couldn’t be denied the eventual obvious parallel between Erotica and American Life in that both offer some of Madonna’s best work despite the critical and public reaction to them. Thus, you had two rather incredible albums from M to kick off the twenty-first century; records that, although not as “classic” as her self-titled debut or Like A Virgin, proved that Madonna was long ago done with concerns about “image” and began focusing almost entirely on the music itself.

Of course, that doesn’t mean the master of reinvention didn’t continue to manipulate an image change to its utmost advantage. Taking something as simple as “disco dolly” (the insult lobbied against her when she first arrived onto the music scene) and making it all her own—even if it originally belonged to the likes of ABBA and Saturday Night Fever. But, as usual, Madonna had a knack for repurposing that which was old and obscure enough to render new again. Constantly having her pop culture reference eye turned to that which she could use for herself, Madonna enlisted Steven Klein for the album’s cover photoshoot, evoking the decadent days of a 70s-era dance floor. Seeming to want to backpedal on American Life, or at least distance herself from its then status as “a flop,’ she chalked up her new musical approach as follows: “When I wrote American Life, I was very agitated by what was going on in the world around me… I was angry. I had a lot to get off my chest. I made a lot of political statements. But now, I feel that I just want to have fun; I want to dance; I want to feel buoyant. And I want to give other people the same feeling. There’s a lot of madness in the world around us, and I want people to be happy.” And so that’s what she made them with a “throwback” that wasn’t quite a throwback because she had never been able to create dance music of this nature when she was actually in the pulsing belly of the beast (namely, Danceteria) in its heyday.

After Confessions on a Dance Floor, Madonna let three years pass (granted, she was in the process of a major world tour from ’05 to ‘06) before pursuing a new project—with an entirely new roster of producers. Even though, by this time, the likes of Timbaland, Pharrell Williams and Justin Timberlake (oh M, you really should have known better about that dude) had grown stale. And it wasn’t characteristic of Madonna to go for producers who were already “it,” preferring instead to tap into people who had yet to “break out.” But this would set a divergent precedent for M’s records going forward. And while Hard Candy might still be looked upon as Madonna’s more overt bid for relevancy in an ever-changing pop music landscape, some of her most memorable bangers do exist on this album, including “Candy Shop,” “4 Minutes” and “Give It 2 Me.” To boot, how could we deny the importance of this album’s existence for the sheer benefit of prompting M to open a chain of gyms named in its honor: Hard Candy Fitness. In short, Madonna, like, invented the pure form of a gay gym without it needing to be “tacit” at places like Equinox.

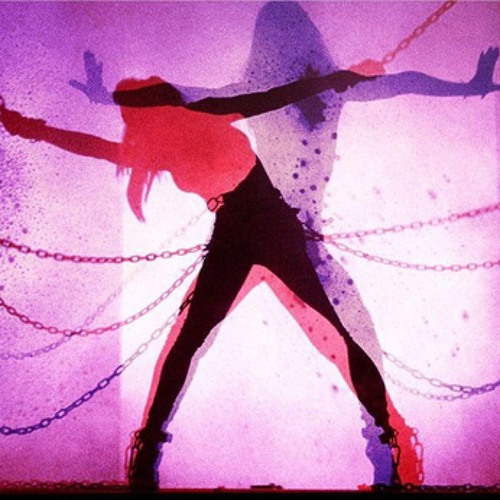

The album that would follow seemed to make it more and more of a challenge for even the staunchest of fans to defend “new” Madonna. 2012’s MDNA is what some might call the product of being on MDMA for the majority of the production. That was certainly the “dance floor sound” Madonna wanted to give off. Only this time it was much moodier than what was presented on Confessions on a Dance Floor, in addition to being brought into the twenty-first century as opposed to tinged with retro, 70s-era sensibilities. What also separated MDNA from Confessions was that it had that “angry” tone Madonna referred to having on American Life. And yes, she was quite angry—specifically at Guy Ritchie, who had cleaned her out of many millions in the wake of their divorce (“You had all of me you wanted more/Would you have married me if I were poor?”). In this regard, MDNA is very much an underrated breakup album that actually has far more grit than the likes of thank u, next. When the songs were rendered into the theatrical performances of the MDNA Tour, they were made all the more profound, particularly an emotional rendition of “Like A Virgin” interwoven into “Love Spent.” Production from Martin Solveig, Benny Benassi and Ray of Light veteran William Orbit solidified an overall danceable-meets-ethereal quality to the record. Plus, like Hard Candy, MDNA inspired another entrepreneurial venture: MDNA Skin.

Another three years later, still committed to music despite the increasing cutthroatness of it (perhaps attracting her all the more), Madonna then brought us 2015’s Rebel Heart. Although this was, hands down, her best work of the 2010s until Madame X came along, it was evidently “born under a bad sign.” Why else would it have been subject to what Madonna called “rape” after the files were ripped from her computer and leaked before being completed or mixed? Taking the Hard Candy concept (hard on the exterior but sweet on the inside) and reusing it as: exploring the contrast between M’s “rebellious” versus “romantic” sides, the original idea had been to make the record a double album. Alas, it was not to be (just like Debra Winger playing Dottie Hinson) and Madonna rushed to get the lead single, “Living For Love,” out, along with five other tracks upon pre-ordering the album on iTunes.

Perhaps soured on the entire rollout experience, Madonna didn’t seem to be in as much of a rush to create another record after this, allowing four years to lapse (her longest since the gap between Bedtime Stories and Ray of Light) before Madame X would arrive in 2019. And yet, as usual, M made it worth the wait. For not only was the album, encore une fois, completely unlike anything in the mainstream (particularly for a white pop star), but it also saw Madonna experimenting with a new sound she, once again, made her own: fado. Drawn to the musical style upon moving to Lisbon for the benefit of her son, David joining the Benfica soccer team, Madonna found herself wandering around her mansion, Norma Desmond-style, not really having any friends to hang out with until one contact invited her to a sort of “happening.” An environment where artists and musicians simply performed for the joy of it rather than concerning themselves with payment. This notion brought Madonna back to her pre-fame days in New York (even though we all know money—before art—was the primary thing on her mind at that time as well). It brought to light the cruel irony of the fact that when you are at your hungriest as an artist, you’re not given the time or freedom to truly explore what your art might do. Yet when you’ve turned into a fat cat by commodifying your art, you’re allowed more time to explore it after having lost touch completely with the common man. C’est la vie—it’s fairly certain Madonna ain’t cryin’ over the dichotomy. And she’s probably learned to stop caring by now that “casual audiences” will never truly appreciate “new Madonna” as the work from that canon should be. As she once commented of being called the “Material Girl” (the very embodiment of “old Madonna”) for the rest of her life, “…when I’m ninety, I’ll still be the Material Girl. I guess it’s not so bad. Lana Turner was the Sweater Girl until the day she died.”

As of M’s sixty-third birthday, she has an equal amount of albums released in the twentieth century as she does in the twenty-first. Should la reine decide to grace us with more offerings (which seems highly likely considering she’s always talking about how Picasso kept painting into his nineties), it might be harder and harder to distinguish where “new” Madonna even begins anymore. Which, one supposes, is what makes the “old” seem so special to people. Apart from the fact that this is the music that’s associated with a period in history that people are increasingly nostalgic for.