There is a message being repeated over and over. A loud and clear truth that no one—even after all that’s happened since both the “election” of Donald Trump and the advent of a major pandemic—seems to want to process in a manner that will generate palpable systemic change (itself requiring the proverbial blow-up of the entire system). That truth, of course, is the fact that capitalism isn’t working. Or it is, but for such a minuscule part of the global population that it shouldn’t take all this screaming and shouting to convince those at the top that what works for some ultimately works for none.

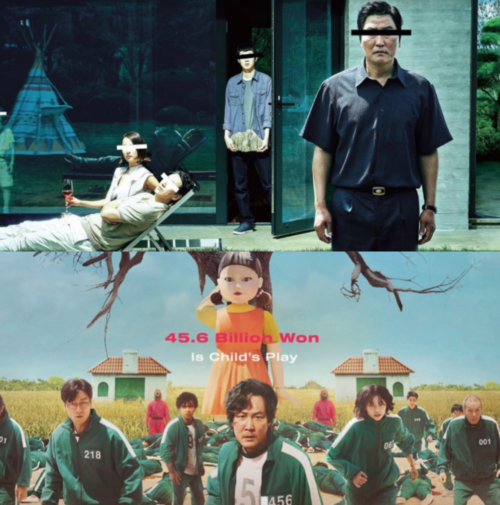

But then, that’s the whole gambit of capitalism, innit? Convince the many who have not benefitted from it that there’s a “chance” for them as well. That they, too, can aspire to one day maybe have some semblance of the success they see paraded before them on various forms of mass communication. The normalization of “middle classery,” however, is not at all the norm for most. But because those who absorb the pop culture that’s “available” (i.e., that’s trending) are indoctrinated with the belief that it is normal, it becomes intentionally “jarring” when that so-called normalcy is pitted against abject poverty—better known as: the real normal. In short, what’s portrayed in both Joon-ho Bong’s Parasite and Dong-hyuk Hwang’s Squid Game. While those who have never experienced the fear and anxiety that come with having to worry about making “regular” ends meet and/or crippling, insurmountable debt might be “skeptical,” both Parasite and Squid Game speak to the ways in which humans can adopt their basest (therefore “most natural”) form as a result of money. Pushed to the brink by what “society” demands via the system that’s somehow deemed “best” for “everyone.”

As mentioned, however, it is only “best” for a select sect of the social strata. Namely, the stratum that already happened to have been born with the requisite silver spoon in their mouth needed to ascend even higher on capitalism’s preordained stratification. For people like the Kim family in Parasite, there is no real hope of ever attaining what the Park family has without quite literally taking it by force. Some might even argue that’s the “purest” form of what capitalism represents. Taking what you feel is yours and “owning” it. Being willing to do whatever is necessary to succeed. The corporate fat cats of the present only learned from the ilk that ran cities and nations back in the day (think: Tammany Hall). Everything is still rigged to go in favor of certain parties over others, and those who don’t have those “odds” are damned to descend ever further into the merde.

What’s worse than the all-out descension, however, is the brief detour of being led to believe there’s one “last-ditch” hope at finally “making it work.” For those in Squid Game, it’s taking yet another major gamble—this time on their own life—to “once and for all” get out of debt. For the Kim family in Parasite, it is the son, Ki-woo (Woo-shik Choi), who serves as the key to igniting that hope when his friend, Min-hyuk (Seo-joon Park), not only gives him a scholar’s rock that’s meant to signify good luck, but also urges him to take over his job as the tutor of a girl named Da-hye Park (Ji-so Jung), who comes from the aforementioned affluent family with the impressive (even if expectedly sterile) house to match.

It doesn’t take long for Ki-woo to get the whole Kim gang in on his scheme—for rich people seem to love nothing more than not only overpaying for a service to give themselves the illusion that it’s somehow better, but simply to be outright ripped off.

Because even if one had to be “cutthroat” to get to the “top” (which typically means inheriting generational wealth), it’s as the father of the Kim clan, Ki-taek (Kang-ho Song), says, “Rich people are naive. No resentments. No creases on them.” His wife, Chung-sook, adds, “It all gets ironed out. Money is an iron. Those creases all get smoothed out.”

The patriarch of the Park family, Dong-ik (Sun-kyun Lee), is a prime example of that when it comes to how dainty he is about smells. Odeurs, if you will. His comment on Ki-taek’s “poverty scent” is summed up when he tells his wife that he smells “like an old radish. No. You know when you boil a rag? It smells like that.” Even their silver-spooned son, Da-song (Hyeon-jun Jung), isn’t too young to differentiate between how “his kind” smells versus “their kind” (the Kims). If only the players in Squid Game had more olfactory know-how to realize that Player #1 must possess a distinctly “rich person’s smell.”

Apart from the commentary on the grotesque nature of our world’s class divide, the major link between Parasite and Squid Game comes toward the middle of the second act in the former, when the Kim family realizes the ex-maid (that they managed to oust with one of their elaborate machinations), Moon-gwang (Jung-eun Lee), has been hiding her husband, Geun-sae (Myung-hoon Park), in the secreted basement of the house for all these years. And the reason why? Because he’s been avoiding loan sharks, obviously. That’s right, rather than risking his life by playing The Game, Geun-sae would rather sit it out in what amounts to a prison (albeit a private, “comfortable” one) in order to evade his fate until he finally dies of his own volition a.k.a. natural causes.

Being that the ways to avoid the inevitable comeuppance of lenders who want their cash paid back in full (with interest, to be sure) are few and far between, the most “creative” way to do so is to go into permanent, Anne Frank-level hiding as Geun-sae does…or to be “blessed” enough with the dystopian opportunity to play The Game furnished for the debt-ridden in Squid Game. And if people thought being in debt was a problem in America (where most students graduate with a mountain of it that they’ll never be able to repay in a lifetime), an article covering the problem of illegal lending enterprises in South Korea noted, “The country is grappling with an underground world of illegal private lending that tempts South Korean citizens—especially business owners—into predatory agreements, complete with business card-toting henchmen on motorcycles who pass out the ads to people in desperation.”

That Parasite and Squid Game have translated to such great success in the ultimate beacon and proponent of the capitalist system, America, should be an indication that this is a problem beyond requiring merely self-congratulatory “awareness.” No, it’s a problem that requires an actual solution. One that politicians are too well-off (out there in their own capitalist bubble) to truly want to solve. Cue the next universally acclaimed South Korean project detailing a story of the proletariat eating the rich, de facto government.